Simon Duffy explores the politics behind poverty in the UK today.

Author: Simon Duffy

This article explores poverty in the UK. Instead of reducing poverty the creation of deeper poverty now appears to be a political ambition. As a society, the UK is demonstrating a terrible lack of self-understanding and a failure of moral integrity.

It was with great pleasure I welcomed the Franco-German Arte Film crew into my home. They were in Sheffield to make a European documentary to explore why - in wealthy Europe - fuel poverty had become such a severe problem. They had many interesting tales to tell of how escalating fuel prices and inequality were combining to harm the lives of so many, across Europe.

In particular they wanted to know why there was such a significant problem in the UK - where 27,000 people a year more people die in winter than at other times ("excess winter deaths") and where many of those deaths seem closely linked to growing fuel poverty. The factors that have created fuel poverty seem closely linked to three inter-linked phenomena:

We ended our discussion by musing on the fate of Europe as a whole. There seems to be good reason to fear that the idea of an increasingly just and friendly society - Social Europe - is now in decline. We seem to be heading to a place of fear, xenophobia and scapegoating - across the whole of Europe. Few governments seem to have any strategy to stop the rot.

Preparing for this discussion also gave me time to pull together some key statistics and, in particular, I spent some time reading the latest Institute of Fiscal Studies analysis of the impact of the UK Coalition Government’s policies on tax and benefits. So in this essay I will summarise my findings and share the relevant graphs.

To begin with I’d like to make some philosophical observations about the subject of poverty, and the connected, but different concept of inequality. For some people the idea of inequality - and here I mean income inequality (which is just one of many possible inequalities) - is obviously wrong and a bad thing. For them any difference in income is an injustice.

There are two problems with this. For me I struggle to see all income differences as unjust. I know many people earn more than me. I do not see this as wrong. I do not envy them their greater income and I do not see my much lower income as unfair. So it doesn’t seem to me obvious that all differences in income are intrinsically wrong.

Second, as the philosopher Robert Nozick pointed out, even if you were able to achieve equality - or any other ideal pattern of income distribution - then a mixture of human freedom and sheer luck (including bad luck) will inevitably mess up your pattern.[1] So, absolute income equality seems like an impossible ideal.

I think this argument is true; but it can also be pushed far too far.

Just because, in a free community, income will vary doesn’t mean, in a just community, people can't put in place measures to limit that variability. We can use tax-benefit policy and many other measures to limit inequality. We can have freedom and justice - this is why the welfare state exists.

So, what kind of limits on inequality should we have? One natural response is to say that we must reduce or eradicate poverty - or in the words of The Gang of Four - “To Hell with Poverty!”

This seems to me to put us on pretty solid ground. It may not be unfair that many people are richer than me, but it seems very unfair that, so many people are so much poorer than me. What is more, the impact of this poverty is so great and so negative. Here are snippets of stories from people in my City of Sheffield:

Sue is a single mum of 39 with two children, her marriage had broken up and she was living in social housing. She has a very low income. Christmas and birthday presents are a luxury she cannot afford. She talked her children through their financial problems and they understood. But throughout the year Sue will spend any small amount of money she has left at the end of the week on low cost presents - a packet of sweets, a new toothbrush - she then wraps them up in big boxes so the kids can have something fun.[2]

Dave has mental health problems, OCD, and an alcohol problem. He lives close to Manor Park Centre. He was a good budgeter, and although he couldn’t afford a television he had a laptop to stay in touch with the world (and he used catch-up TV on the laptop). He couldn’t afford to keep his flat warm - but he would go to the pub to stay warm. Last summer he was walking with a friend in the Peak District and he slipped and fell - he became house bound. The church, family and friends rallied round - but this crisis led to big benefit problems. He couldn’t afford to get to the physiotherapist, his loss of benefits, debt and other problems piled up. In the end he got an admission into the mental health system. David is out at last, but he is now frightened about his future - he feels he is just surviving.[2]

John can’t afford to make pancakes with eggs, so he makes them without.[2]

Bill used to disappear around December, and came back in March. When asked he explained “I get myself locked up” Prison gave him the support he needed to cope with the winter. “It’s warm, free meals and plenty of company.[2]

In a wealthy society like ours there is no need for any of this. Poverty like this cannot be acceptable; however, if our target is to eradicate poverty then this leaves plenty to think about.

Relative poverty - One argument is that poverty should be understood as a matter of degree. I am poorer relative to the number of people who are wealthier than me and the degree to which they are richer than me. On this view, justice may not demand absolute equality, but it does demand a certain degree of equality. For example, Plato argued that the degree of inequality allowed in a just society would be 1:5. That is that the rich must have no more than 5 times the poor.[3] [In the UK the top 10% of families have a post-tax income which is 14 times greater than the poorest 10%.] On this model the goal of eradicating poverty is replaced by the goal of limiting income inequality.

Absolute poverty - Another argument is that poverty is only a moral concern if it is really a block to people’s development or a real source of misery. Absolute poverty is not relative - it is something you can have more or less of - in fact if your focus is absolute poverty then you may be able to eradicate poverty all together. This does not mean that poverty is exactly the same thing at all times and all places - absolute poverty would still need to be defined relative to a particular time and place. Instead we would define what poverty means - absolutely - for our society, today.

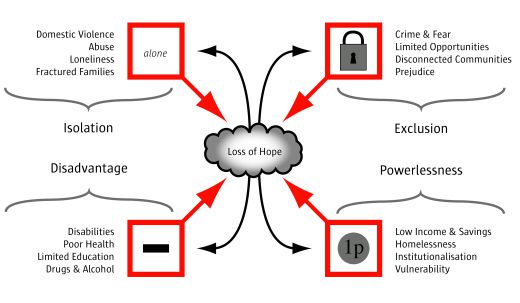

Also it is important to define poverty to include more than money. A decent life isn't something you can just buy. Poverty, properly understood, is not just a matter of an absence of money (which is one useful means for positive personal change - but a rather limited one). Poverty is an absence of a number of critical dimensions of real wealth.[4] Dr Pippa Murray developed this useful model of real wealth, and working with WomenCentre in Halifax we developed a parallel model of real poverty:[5]

Figure 1 The Nature of Real Poverty

Although a model of Absolute Poverty seems to suggest that we can eradicate poverty without being concerned with income distribution (for nobody gets poorer just because somebody else gets richer) this is probably false. There is plenty of evidence that a high degree of inequality makes people feel poor, unworthy and anxious. Inequality is therefore damaging to them and to the whole of society. So income inequality should be treated as one part of our understanding of poverty.

An interesting medieval concept which I also think we should also start paying more attention to is sufficiency. The ideal of sufficiency is that human beings need a certain level of wealth - that which is enough or sufficient - but too much (just as too little) is bad for us:

I neither say nor maintain that kings should be called rich any more than the common folk who go through the streets on foot, for sufficiency equals wealth, and covetousness equals poverty.[6]

We have certainly lost sight of the moral dimension of poverty and inequality. We have forgotten to consider the corrupting influence of envy, of greed and of the pride that can come with excessive wealth. More is not always better.

One of other important ideas that we must also consider is whether poverty is constructive or destructive of wealth. That might seem like nonsense, but one the key arguments of the 1970s was proposed by the philosopher, John Rawls; he argued that if it were true that some degree of income inequality raised the standards of living of the poorest themselves, then such a degree of inequality would be justified.[7]

And it is plausible that a degree of inequality is productive in this way, for it is linked to the idea of incentives. In a world where no one could become personally richer than anyone else then there would be no financial incentives to strive, innovate or take risks. And, arguably, it is through such processes that wealth or growth becomes possible.

In a sense he was saying if absolute poverty is reduced by increasing relative poverty then it would be okay to increase relative poverty. Interestingly a very different version of the same argument has come to be called ‘trickle-down economics’ - the idea that high earnings by some, will, eventually, increase the incomes of the poorest.

However there has been a big jump in the argument here.

Rawls was arguing inequality is only justified if it leads to improvements for the poorest. Trickle down economics has turned this conditional imperative into an absolute imperative - let the rich become richer, in the hope that this might improve the position of the poorest. This is a jump far too far and is not supported by the evidence. Excessive inequality seems just as destructive or wealth as does extreme equality.

The World Bank lists the United Kingdom as the 24th wealthiest nation per capita (in Europe it ranks 13th after Luxembourg, Norway, Switzerland, Netherlands, Ireland, Austria, Sweden, Germany, Denmark, Iceland, Belgium, Finland, and one above France who are 14th).[8]

The World Bank Index of inequality lists the United Kingdom as:[9]

In other words, the UK is a world leader in inequality - but a real slacker in terms of wealth. All the countries that are wealthier than the UK in Europe are more equal than it - most of them are world leaders in income equality. So, while there may be an argument that a certain degree of relative poverty enables reductions in absolute poverty, it is clear that the UK has far too much relative and absolute poverty, and far too little equality.

There are many ways of understanding the degree of poverty in the United Kingdom, here are some statistics that might help explain how big a problem poverty is:[10]

High energy costs seem to hit people in poverty particularly hard:

From a poverty perspective: the households with high energy costs living in poverty or on its margins in 2009 faced extra costs to keep warm above those for typical households with much higher incomes adding up to £1.1 billion.[11]

From a health and well-being perspective: living at low temperatures as a result of fuel poverty is likely to be a significant contributor not just to the excess winter deaths that occur each year (a total of 27,000 each year over the last decade in England and Wales), but to a much larger number of incidents of ill-health and demands on the National Health Service and a wider range of problems of social isolation and poor outcomes for young people.[11]

Households in England and Wales cut their energy use by a quarter between 2005 and 2011 as prices soared, government figures show. The sharp fall was probably caused by a mix of efficiency measures and environmental awareness, as well as steep price rises, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said. Households have faced steep price increases in recent years as wages have remained frozen, squeezing budgets. Average bills have risen by 28% in the last three years, industry regulator Ofgem said.[12]

Fuel poverty is a major social crisis in the UK. There are over five million households in fuel poverty needing to spend more than 10% of their income on energy in order to keep warm. This number will increase significantly if gas prices rise as the Government expects.[13]

The UK ranks so low despite the fact that it has amongst the lowest gas and electricity prices in Europe and relatively high household incomes compared to the other countries. And yet it has the highest rate of fuel poverty and amongst the highest rate of excess winter deaths. In this context, the poor energy efficiency of our housing stock emerges as the main cause of these problems. David Cameron recently pledged that he wanted the UK to become “the most energy efficient country in Europe”. This ambition is all the more laudable and appropriate because this fact-file finds that presently, the UK can only be characterised as the ‘cold man of Europe’.[13]

Gas and electricity bills are still the biggest household spending worry – only slightly reduced from 2013. Ed Miliband attempted to capitalise on the success of his 2013 energy price freeze on Sunday, when he told Andrew Marr that the regulator, Ofgem, should have powers to force energy companies to pass lower wholesale costs on to consumers. The Labour leader said he would demand fast-track legislation on energy in a Commons debate this week, so that the regulator could make prices for consumers reflect the falling price of gas and oil. New YouGov research reveals that gas and electricity bills are still the household cost most worried about by voters, although anxiety over energy prices has receded since 2013.[14]

It is also clear that fuel poverty, like poverty itself, is a much bigger problem in the North and in the South West of England.[15]

Fuel poverty is described by some as the choice to heat or eat. How can a wealthy society like the UK by forcing its own people to make such a choice?

The purpose of the welfare state, you would think, is to reduce absolute and limit relative poverty. The duty of Government would, therefore, be to introduce policies that address problems of absolute poverty - like fuel poverty; and also to reduce income inequality. However this is no longer the case. Despite the UK’s already high level of income inequality and poverty, the UK Government has set about purposefully increasing poverty.

Government policy, particularly since 2010, has focused on reducing the incomes of the poorest in the UK by a series of measures:

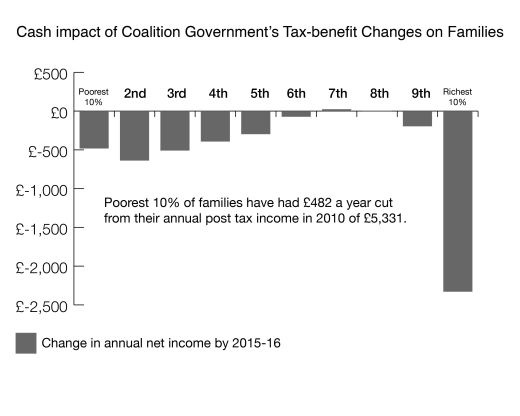

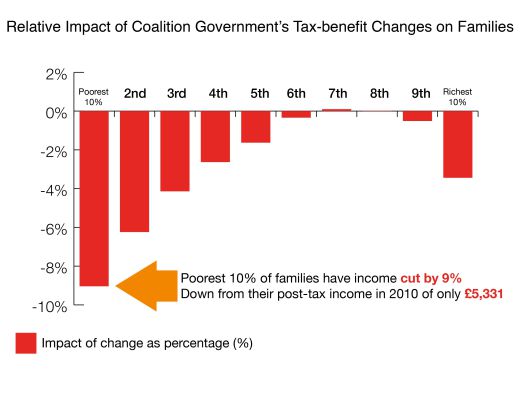

The most obvious of these are changes to the tax and benefit system. A recent report from the Institute of Fiscal Studies by Browne and Elming The effect of the coalition’s tax and benefit changes on household incomes and work incentives provides the most comprehensive data to date of the combined impact of tax and benefit changes.[16]

Low-income working-age households have lost the most as a percentage of their income from tax and benefit changes introduced by the coalition, mainly as a result of benefit cuts... Middle-income working-age households without children have gained the most from the Coalition’s changes. They have gained significantly from the coalition’s large increases in the income tax personal allowance and are much less affected by benefit cuts.[16]

More detail on the breakdown of the cuts is provided in the table below.

| Policy Change | Cost | Saving |

| CPI-indexation | £4,260 | |

| State pension protection | £4,590 | |

| 1% extra cap to benefits | £1,740 | |

| Increased child tax credit | £1,625 | |

| Below CPI indexation | £1,605 | |

| Means-testing ESA | £1,475 | |

| Below inflation increases to working tax credit | £1,320 | |

| Changes to tax credits | £1,295 | |

| Abolition of child trust fund | £580 | |

| Lone parent benefit | £355 | |

| Other benefit cuts | £1,865 | £12,100 |

| Benefits Sub-Totals | £8,080 | £24,730 |

| NET CUT to Benefits | £16,650 | |

| Increased VAT | £13,980 | |

| Increased NICs | £11,817 | |

| Tax allowance changes | £7,988 | |

| Reduced pension tax relief | £5,005 | |

| Fuel duty cuts | £3,260 | |

| Reduced corporation tax | £7,615 | |

| Bank levy | £2,900 | |

| North Sea supplementary | £1,815 | |

| Small profit rate reduced | £1,400 | |

| Others | £30,475 | £28,796 |

| Taxes Sub-Total | £50,738 | £64,313 |

| NET TAX INCREASE | £13,575 |

So - in total - the Government has reduced spending annually by £30 billion through a combination of tax and benefit changes. However, most of these cuts appear quite technical and they are hard to see. For example, while £25 billion per year will have been been cut from benefits in 2015-16, the biggest single cut has been caused by changing how benefits are “indexed” - which is how they change over time. This subtle but vicious cut is worth in 2015-16 alone just over £4 billion (17% of the cuts). Each year the value of this cut will grow - like a never-healing wound.

Also there are multiple smaller cuts. In fact the majority of benefit cuts and tax increases are invisible and have only been included under the category 'others.' This is truly, death by a thousand cuts.

Browne and Elming also calculate where the cuts fall:

Figure 2 Cash Impact of Coalition Tax-benefit Changes on Families

We can compare this cut to ONS data for household incomes in 2009-10 to see the net effect of Government policy:

Figure 2 Relative Impact of Coalition Tax-benefit Changes on Families

In 2015-16 the annual cut to the incomes of the poorest 10% will be equivalent of about £500 per year - that’s 9% cut in post-tax income. This is an extraordinary intentional attack on the incomes of the poorest.

Even describing vicious cut in the incomes of poorest doesn’t do justice to the true size of the problem. Poverty is made even worse by a variety of cost increases, that also target the poorest:

So, unsurprisingly, the number of people and the proportion of people in absolute poverty has been growing since 2010/11.[18] The consequences of all this hardship are probably reflected, not just in excess winter deaths, but also in poor mental health. For example, there are signs that the rate of suicide has now started to rise:

In the summer of 2013, the UK’s largest mental health charity, Mind, reported an unprecedented 50% rise in calls to its national helpline for the twelve months up to March 2013 (this was on top of a rise of 100% in the previous year for money-related calls). The distinguishing feature of the calls was first, that more of the callers said they were contemplating suicide compared with pre-recession figures and, second, that ‘severe financial worries’ were increasingly be cited.[17]

Samaritans reported that there were already indications of a ‘significant increase’ in UK suicides between 2010 and 2011 (running at its highest level since 2004, up from 11.1 to 11.8 per 100,000).[17]

Why is all this happening? How has the welfare state gone into reverse? Is this all some dreadful plot?

One of the most important factors driving Government policy is that scapegoating innocent groups is always a popular policy - especially in a time of general anxiety. Politicians have largely abandoned a certain reticence about deploying vicious and stigmatising rhetoric, instead even Government Departments have adopted the rhetorical devices of the politicians:

An examination of Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) speeches and press notices connected to benefits in the year to April 1 shows a significantly increased use of terms such as "dependency", "entrenched" and "addiction", when compared with the end of the Labour government. Fraud, which accounts for less than 1% of the overall benefits bill, was mentioned 85 times in the press releases, while it was not used at all in the final year of Labour, which was itself accused of sometimes using intemperate language on the issue. In the 25 speeches by DWP ministers on welfare over the year, "dependency" was mentioned 38 times, while "addiction" occurred 41 times and "entrenched" on 15 occasions. A comparison of 25 speeches on the subject by Labour ministers saw the words used, respectively, seven times, not at all, and once. Some charities warn that such language fuels a distorted portrayal of benefits in parts of the media, which in turn perpetuates widespread myths about the welfare system. A YouGov poll for the TUC last year found that, on average, people think 41% of the welfare budget supports the unemployed – the true amount is 3% – and believe the fraud rate is 27%, as against the government's estimate of 0.7%.[19]

We must not under-estimate the brute fact that politicians need popular support. If injustice can be manipulated into a vote-winning tool then it takes a great deal of integrity to avoid using that tool.

One reason for the popularity of injustice is growing atomisation and a reducing sense of solidarity and community. When the welfare state was developed, at least in the UK, it was on the foundation of organised social structures that served to unite people locally and represent people nationally. Today these structures are much weaker:

Isolation, as Arendt observes, breeds fear not a sense of equality. And when people are fearful they rush to join whatever side seems most like winning:

Thus the common ground upon which lawlessness can be erected and from which fears springs is the impotence all men feel who are radially isolated. One man against all others does not experience equality of power among men, but only the overwhelming, combined power of all others against his own.[20]

Contrary to popular myth - oppression and injustice do not naturally provoke resistance and revolution. It takes something more to unite people in the name of justice.

A further factor is that The UK’s democratic system tends to focus on a very narrow group of middle income or median income earners. These are the groups that have benefited most obviously from tax-benefit changes. At the same time politicians pander to the insecurities of this group, using terms such as:

Rhetorically this serves to fabricate a group of non-working people who are somehow illicitly benefiting from the efforts of the middle-income groups.

In addition The UK has pursued policies of deliberately reducing workers rights and increasing labour price flexibility since 1979. Even during the three Labour Governments (1997 to 2010) there has been a reluctance by all leading politicians to limit the ‘supply of Labour’ into the market.

The result is curious - the UK has very very high levels of employment - the UK's employment rate is 69.9% (only just below Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and Austria) and the UK's unemployment rate is also relatively low 6.3%.[21] So the UK has managed to achieve a combination of high employment and high inequality. This is reflected in very low salary levels for many, with 5.2 million people in the UK earning below the Living Wage.[22] This is bad economics.

Yet despite this fact there continues to be a bizarre faith in the idea that forcing more people into increasingly inefficient and poorly paid work is the answer. There are few prepared to challenge this orthodoxy and to start asking better questions.

Debt in the UK is primarily private - not public. While the Government did spend a large amount to bail out the banks the primary debt problem was over-lending by the banks to home owners, in the context of a rapidly rising housing market. As house prices rose banks were prepared to lend more and more money on the basis of the house purchased and its higher value. In other words bank lending fed a house price bubble and a house price bubble supported unsustainable lending by the banks.

It is never observed that the big winners from this are the better-off who gained most from house price inflation and yet who have not been made to pay for their excessive borrowing. Since the crash the Government has not only provided money to banks but also set interest rates at minimal levels - effectively subsiding the excessive borrowing of the better off. At the same time those in poverty are increasingly forced to borrow from lenders who will charge excessive rates for short-term loans.

The net effect of Government policy is to provide an annual subsidy of £10 billion to the better off.[23]

Looking at these facts and figures it would be easy to agree with those who blame this worsening situation on ‘Thatcherism’ or ‘Neoliberalism’ and certainly there is an ideological dimension to this. Some people do genuinely believe that these kind of theoretical justifications for selfishness have real meaning and they do try to persuade others to their twisted point of view.

But I am not convinced that neoliberalism is the real enemy. For, in fact, even some of those who use such arguments know very well that they are largely do so - for effect. Most people do believe that decency, fairness, equality and justice matter. What we have lost is any sense of how these things can actually be achieved.

Our values and our sense of how the world actually works have drifted far apart.

For politicians everything depends on achieving power - that is the game they are in. If they discover that, in a time of crisis, xenophobia, scapegoating or stigmatisation work as rhetorical devices to win power then it is hard for them to resist. And when standards start to drop, then it is very hard to find the moral integrity to resist following those standards downhill. In the UK the phenomenon of Nigel Farage and UKIP typifies the way in which popularism easily trumps integrity in a political system dominated by media appearance and the need to win over those ‘swing voters’

Again, looking at the data on tax-benefit changes, it is clear that the target of policy is to pander to to the moderately better-off with tax breaks, mortgage subsidies and a rhetoric which reassures then that they have done nothing wrong - someone else is at fault - someone poor, someone foreign or even someone much richer than them.

We have to start to recognise that we live in a medianocracy - the median voter is king - as far as politicians are concerned. The interests of most people, or the interests of the poorest, are easily sacrificed if you can win the support of the key voting groups.

This also suggests that the response to injustice must be thoughtful. We cannot simply go back in time to 1945 - for after all, we’ve already been there, and this is still where we ended up. We need fresh thinking about what social justice means and how to achieve it.

For myself I think that means we need to take seriously real poverty and real wealth - I still think a good principle of justice is an unwavering commitment to those in the worst situation. But we also need to be able to think beyond a concern with income on its own - we need to think about the other elements that make up a good life - in particular relationships and community.

In the same way we will need to think differently about how to protect social justice in future. We must not lose sight of the importance of the welfare state and the role of political system - but perhaps we need to give more thought to the deeper constitutional issues that underpin that system. If it has been so easy to attack the poor and reduce justice then clearly this is a constitutional issue.

And constitutional does not just mean central or Parliamentary. We need to think about the social and community structures that exist. Churches, communities, councils, cooperatives and charities all must look again at their own role in sticking up for people. The collapse of civil society and the trade union movement has obviously been critical in undermining solidarity and attention to the needs of other people.

The Centre for Welfare Reform is going to continue to set out positive ways forward in the knowledge that justice - while never easily attained - is always worth striving for.

1. Nozick R (1974) Anarchy, State and Utopia. London, Blackwell.

2. Duffy S (2014) Listening Up To Poverty. Sheffield, The Centre for Welfare Reform.

3. Plato. The Laws

4. Murray P (2010) A Fair Start. Sheffield, The Centre for Welfare Reform.

5. Duffy S and Hyde C (2011) Women at the Centre. Sheffield, The Centre for Welfare Reform.

6. de Lorris G and de Muin J (1994) The Romance of the Rose. Oxford, OUP.

7. Rawls J (1971) A Theory of Justice. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

8. GDP per capita, PPP (current international $), World Development Indicators database, World Bank. Database updated on 16 December 2014. Accessed on 20 December 2014.

9. World Bank GINI index, accessed on 7 April 2015.

10. Gordon D et al. (2013) Impoverishment of the UK. PSE UK, ESRC (2013)

11. Hills J (2012) Getting the Measure of Fuel Poverty - Final Report of the Fuel Poverty Group. London, Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion.

12. Farrell S (2013) Households Cut Energy Use By a Quarter As Prices Soar. The Guardian, 16th August 2013

13. Association for the Conservation of Energy (2013) The Cold Man of Europe. London, Association for the Conservation of Energy.

14. https://yougov.co.uk/news/2015/01/14/energy-biggest-household-concern/

15. Climate Just analysis of Department of Energy & Climate Change, Fuel Poverty 2012 data

16. Browne J and Elming W (2015) The effect of the coalition’s tax and benefit changes on household incomes and work incentives. London, Institute for Fiscal Studies.

17. O’Hara M (2014) Austerity Bites. Bristol, Policy Press

18. Households Below Average Income (HBAI), UK, Department for Work and Pensions 2014

19. Walker P (2013) Government using increasingly loaded language in welfare debate. The Guardian, 5 April 2013.

20. Arendt H (1994) Essays in Understanding 1930-1945. London, Harcourt Brace & Company

21.Wikipedia: List of sovereign states in Europe by unemployment rate, accessed 9 April 2015

22. Helm T (2013) More than 5 million people in the UK are paid less than the living wage. The Guardian, 2 November 2013.

23. Duffy S (2013) The hidden Housing Subsidy. Sheffield, The Centre for Welfare Reform.

The publisher is The Centre for Welfare Reform.

Poverty UK © Simon Duffy 2015.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.