Mike Grady makes the health case for radical cross-government reforms to end poverty, reduce inequality and building a fairer society.

Author: Dr Mike Grady

Dr Mike Grady (is a management consultant) and a version of this paper was delivered at the Yorkshire Branch of the Socialist Health Association.

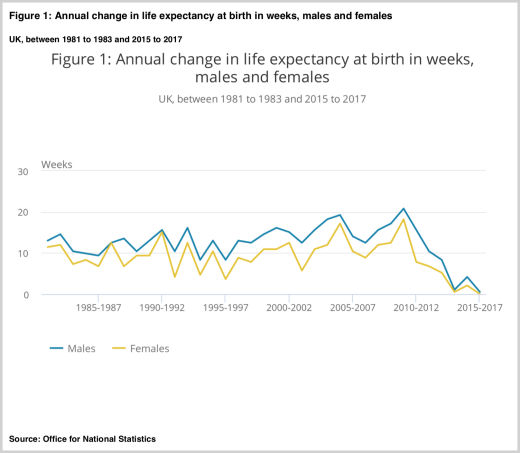

ONS have recently reported that life expectancy in the UK has stopped improving for the first time since figures were recorded in 1982.1 Life expectancy from birth for women is 82.9 years and for men 79.2 years. In Scotland and Wales a decrease in life expectancy has been evidenced whilst England and Northern Ireland have stalled.

This stalling of life expectancy is linked to a higher number of deaths for 2015/2017 coinciding with a bad flu season and excess winter deaths. There is an ongoing debate on the causes and future direction of this trend. Some have argued that governmental austerity policies including reductions in social care and other public services as well as welfare reform have contributed.

The evidence shows that the UK lags behind other countries in life expectancy and that those countries with high standards of education and welfare foster the conditions within which citizens flourish.2 This and the global financial crisis as well as widening health inequalities raises significant questions about the relationship between The State, local communities and individual citizens and policy approaches to address inequity and deprivation.3 Traditional models of paternalistic welfare are being challenged with a new perspective and the development of a new contact to deliver greater participation, health equity and social justice.

Fair Society: Health Lives the strategic review of health inequalities in England post 2010 gathered together the best global evidence to guide policy and practice to achieve a fairer of health and a narrowing of the health gap.4

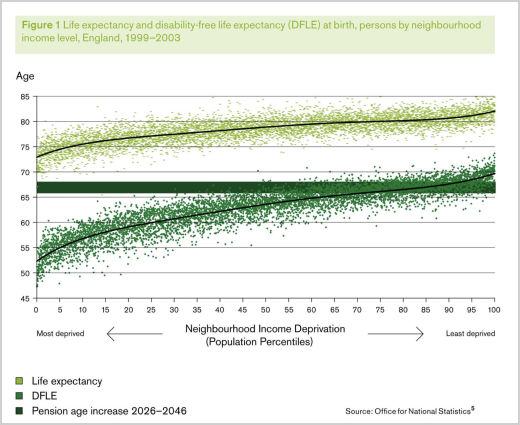

The evidence and analysis demonstrates that people with higher economic status have a greater range of life chances, more opportunities to lead flourishing lives and enjoy better health. Consequently the links between the social conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age become crucially important. The differences are observed as a social gradient with life expectancy declining with every step down the income scale.

The steepness of that social gradient become significant with health and social problems being less frequent in countries with narrower income inequalities and developed education and welfare systems. Health inequalities accumulate throughout life and any policy responses need to address inequality across the life course.

The human cost is there for all to see. People in the poorest areas are in poor health longer and die sooner than those in more affluent areas. There is also an enormous financial and economic cost if health inequalities are not addressed. Both the human and economic case for measured and concerted action is compelling with action at national and local levels across the social gradient. Too often actions have focussed on the bottom of the gradient which does little to alter the steepness and ultimately has limited impact.

The Marmot Review recommended action on the social determinants of health through 6 key policy objectives:

Action consistent with these policy recommendations was identified as essential if the social determinants of health were to be tackled across the social gradient and if greater fairness and social justice was to be developed. It is unlikely that any one single strategy or action which relies upon intervention in one part of the system will be effective or create the synergy necessary to reduce overall health inequalities.

Improvements in life expectancy at birth which had been 1 year increase every five years for women and every 3.5 years for men have slowed since 2010 to 1 year increase every 10 years for women and every 6 years for men.

Similar increases in renaming life expectancy at age 65 years have also faltered. There are many potential explanations for this with a key factor in the increasing role played by deaths at older ages. This has shown a sudden and sustained increase in such deaths Dementia rates among those aged 85 and over have been rising since 2002 Dementia and Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of death in women over 80 and men aged 85. Increasing rates of dementia and the substantial and continuing increase of the larger population at older ages has placed pressure on health and social care services.

The Royal College of Paediatrics highlight that infant mortality rate for England and Wales has risen for the last two consecutive years.6 The rate was already 30% above the median for 15 EU countries. Even if it begins to decline again it would still be estimated to be 80% higher than EU 15+ by 2020. Key risk factors are higher levels of women smoking in pregnancy in the UK and lower levels of breast feeding. Additionally child poverty rates which are expected to increase by 40% in the next decade will impact detrimentally. Poverty lies at the root of many of the risk factors for infant mortality and all of child health.

Some improvement can be identified in levels of development of children commencing schooling. In 2015/6 70% of children were found to have a good level of development up from 50% in 2012. However children living in poorer households had significantly lower figures.7

Inequalities can be reduced if inequalities in educational attainment are minimised. However there has been little change in the number of young people attaining 5 GCSEs including Maths and English. 60% of all young people achieved the goal but only one third of young people living in poorer households.

Despite a fall in unemployment rates there has been a significant increase in the numbers of people who do not have sufficient income to live at an acceptable standard. In London, the West Midlands, the North East, the North West, and Yorkshire and the Humber 3 out of 10 people are in this position. The recent report by Social Marketing Foundation found more than a million people are living in food deserts – neighbourhoods where poverty, poor public transport and a dearth of big supermarkets severely limit access to affordable fresh fruit and vegetables.8 Estates in Hull, Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham are catalogued. The biggest barrier to healthy eating was poverty. 4 Million Children are estimated to live in households who struggle to afford healthy food to meet official nutritional standards. Between 2002 and 2016 food prices rose 7.7 whilst incomes of the poorest families fell 7.1%. A Cambridge University study found people on low incomes who live furthest from Supermarkets are more likely to be obese.9 Use of foodbanks has increased significantly as austerity bites.

Principles to address the social determinants of health include:

A framework has been set out relevant to efforts to address health inequality and narrow the health gap. Current policy initiatives are not addressing key issues of the social determinants of health and impact detrimentally on the health of the nation. Social inequalities in health arise from the inequalities in the conditions of daily living with social position shaping health status and wellbeing with a focus on the social determinants of health. Single agency responses to such complex problems are insufficient. More radical action is required across the whole system nationally and locally providing transformational leadership in partnership with local people and communities. This would centre on extending democratic participation using more asset based approaches to facilitate co production of strategies and services in a new power relationship between the public, professionals and political leaders. The focus should be on building greater equity, confidence and resilience allowing people to take control of their lives within stronger social networks and more resilient communities.

References

The publisher is the Centre for Welfare Reform

Health Needs Equality © Dr Mike Grady 2018

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

health & healthcare, local government, politics, tax and benefits, England, Article