Argument for a profound shift in control towards local communities and the outline of a new strategy for local government.

Author: Simon Duffy

The growing rhetoric of decentralisation is matched only by the growing reality of increased centralisation. Yet this paradox seems to go unnoticed in the mainstream media. It is time to explore what real and radical localism might look like and start to organise for the kinds of constitutional reforms necessary to halt the creeping extension of central power.

In theory almost everyone seems to believe that power and control should shift towards local communities; in practice the UK is not only the most centralised welfare state in the developed world - it is also becoming more centralised.

The latest stage in the process of disempowerment process is paradoxically called ‘localism’. It seems to involve:

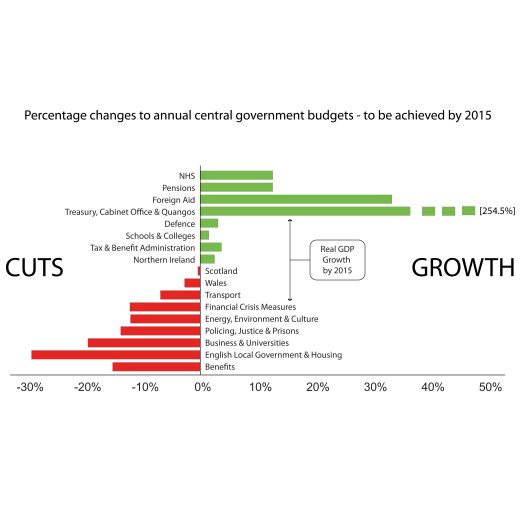

The chart below shows that the greatest cuts have been to local programmes and the individual incomes of people in local communities, the greatest increases have been for centralised programmes. The centre of the centre - the Cabinet Office and Treasury have grown to such an extent that it is impossible to fit their figures on the chart:

This is not a recent event nor a matter of party politics or ideology. Although these recent cuts to local government are unlike any we have seen before the on-going deterioration in local autonomy is not new. Previous governments also talked about increasing local control and democracy, while in fact undermining it.

There are a number of reasons why power is pulled in greater concentration to the centre, to London.

Despite the rational case for shifting power to localities the brute fact is that power brings the rewards of power and status to those who wield it. Government ministers, think-tanks, civil servants and the CEOs of large private service providers all have a vested-interest in keeping decisions local to them - in Whitehall.

The party in power in Westminster is usually in opposition in most local communities. These areas can then be targeted and blamed by the ruling party for their local failures.

There is no effective voice for local government. The very party political system which leaves local government vulnerable on the ground seems to lead to a stalemate at the level of national umbrella organisations. There is no effective advocate for local government on the national stage.

Local government lacks any constitutional guarantee of its rights, its role or its structure:

This marks one of the factors that is peculiar within the UK. Other welfare states have established local and regional structures which are much more robust - set in constitutional law and reflected in national democratic structures.

Even where a new responsibility has been added to local government the detailed story demonstrates the negative relationship between local and central power in the UK. In 1980 central government created an entitlement for residential care called Board & Lodging, which could be claimed by residential care home owners. From 1979 to 1990 the numbers using this entitlement to enter residential care jumped from 12,000 to 199,000. This marked a significant policy failure by central government: expenditure ran out of control and new forms of institutional provision developed.

Central government had effectively created the residential care industry by an incompetent central subsidy.

In order to stop this haemorrhage in public funding it was decided to cap the level of funding and transfer this funding to local government. This was the central policy decision of the 1992 NHS and Community Care Act.

In fact the very success of local government in taking responsibility for adult social care and introducing new innovations and efficiencies probably marks the beginning of a new period of effective centralisation.

Adult social care funding will be squeezed - unlike centrally funded programmes like health and education and despite the preventative efficiencies of social care it is adult social care that will have to be cut.

Funding for adult social care may be nationalised - eventually a new social care settlement will probably create a nationalised insurance model and further weaken local discretion. The strange way in which local success is then twisted to the advantage of centralised power can be further demonstrated by the development of personalisation in England.

In 2003 self-directed support was being developed in 6 local authorities by the In Control project. By 2006 over 60 local authorities had joined the programme, despite significant reservations by central government about an approach that would shift power and resources into the hands of local citizens. Many local leaders went onto put increasing levels of pressure on the Department of Health; which in turn led to the publication of Putting People First.

However, when personalisation became national policy civil servants shifted their role from resisting personalisation into one of imposing personalisation upon local government. They then set about imposing targets, incentives, regulations as if they needed to force personalisation onto the very local leaders who had developed these ideas. And unsurprisingly many of these centrally-led initiatives were poorly thought-through, wasteful or inconsistent with other central policies.

Central government enjoys spending money; but it has a poor understanding of the real needs of people or communities.

We can see the same peculiar pattern at play in the development of what became known as Total Place. On the face of it Total Place is an eminently sensible policy goal - let local leaders shape all local resources to achieve locally defined goals and objectives in ways which are sensitive to local needs and local opportunities and structures.

But what is the reality of Total Place? In fact it is almost impossible for local government to really exercise the necessary control or influence over the vast majority of public resources that are spent within the area:

In fact we seldom seem to ask why the policy of Total Place is needed in the first place. Total Place is appealing because it reflects how things ‘should be’ - in a rational world. But the policy is only needed because the reality is that local government has been left to pick up and reintegrate funding streams and organisations that have been separated by central government.

Total Place is a Humpty-Dumpty strategy: local government is being asked to put together the pieces of funding that was divided in Whitehall - an impossible task.

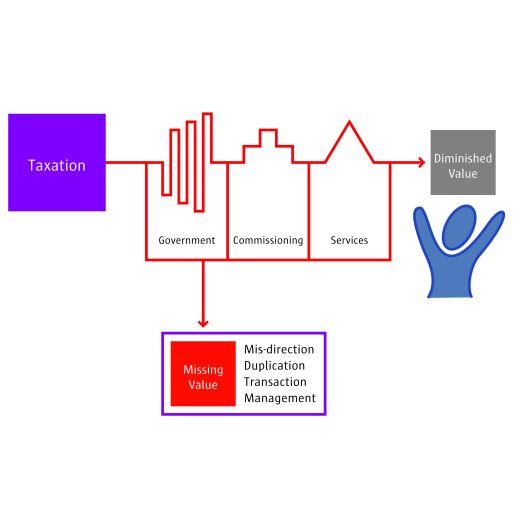

In fact the whole of the current welfare system is deeply inefficient. (a) Resources are extracted from local communities through the various tax systems, (b) pooled - largely within Whitehall - (c) divided into government departments and benefits and then they (d) pass through central and local systems into services, often with management and transactional waste at every level.

By the time those resources are then return to local communities they have diminished in size and been divided into multiple streams for competing purposes.

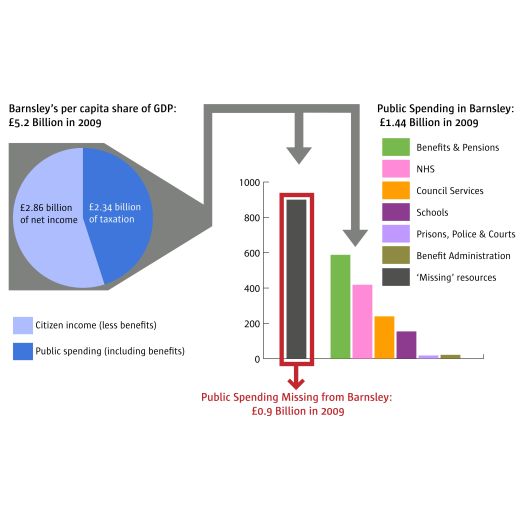

We can take this analysis even further by examining the public resources that are spent in a local community. For example, let us take Barnsley:

So, looking at the main elements of public expenditure, total public expenditure in Barnsley is approximately £1.44 billion.

This means that Barnsley controls only 16% of actual public spending in Barnsley.

In 2009 per capita GDP was estimated at £23,000. For the UK as whole this is £1.38 trillion, for Barnsley - with a population of 225,200 that gives a proportionate figure of £5.2 billion. Government expenditure for 2009-10 was approximately £670 billion (45% of GDP figure), hence the share of that which one might expect to be spent in Barnsley, other things being equal, would be £2.34 billion.

In other words there is a significant discrepancy between the size of government expenditure for the UK and the size of public services and income transfers into Barnsley. Approximately £0.9 billion has gone missing.

This means that Whitehall has wasted at least 39% of Barnsley's funding - before that funding has even been returned to the local community.

Further - this means that Barnsley controls only 10% of Barnsley's rightful share of public expenditure.

Of course it may be objected that the figure of £5.4 billion as the hypothetical Barnsley GDP is not real. And this may be true, but if so this counts for my argument. For this suggests that Barnsley is doubly disadvantaged by current arrangements:

The size and complexity of the various funding transfers from local citizen - to central government - back to local services - seems to obscures the fundamental injustice of the current welfare settlement. Places like Barnsley are made to feel that they are somehow dependent upon the centre - but this illusion is created by a sleight of hand. Barnsley has been cheated.

As we discussed above, there are many explanations for this kind of mistreatment of local communities like Barnsley. But perhaps there is an even deeper explanation than these merely structural factors. At a recent seminar on public policy and localism, within a London think-tank, one of the participants - an employee of a large private-sector employment service (that is working with the DWP to take over employment services nationally)said:

“But Barnsley could not survive on its own. Barnsley needs Chelsea.”

This is false; but it is a false assumption that runs right through the Whitehall establishment.

Whitehall, and the elites which circle around it, want to believe that the provinces are incompetent and need their support in order to survive. But of course these are views are self-serving nonsense. It is just easier to justify taking control of power and money if you also believe that you are better than the people whom you serve.The name for this powerful cultural assumption is meritocracy - that power should belong with the ‘best’ - and it turns out that those with power (of both Left and Right) always like to believe that they are the best.

But they are wrong.

This easiest thing would be for things to continue as they are. It is tempting to hope that the next political party will resolve these issues from the centre. It is nice to think that one day localism might be real and that someone else may deliver localism to our communities. But this is not realistic.

Power will not shift to local communities unless those communities find ways of organising themselves differently, unless leaders emerge who will stand up for their local communities, unless we develop a new account of how the whole system should work. In particular local government cannot expect to be part of a new and more just settlement unless it finds a way of making the case for change itself.

Here are some initial thoughts about the practical things that could be done by local government to shift the pattern away from meritocratic centralisation and towards genuine localism.

As local power is eroded it may become easier to change focus. Instead of pretending to be an agent of central government it may be more helpful if local government begins to really see how it can help articulate and defend the rights of local citizens - particularly with respect to centralised services:

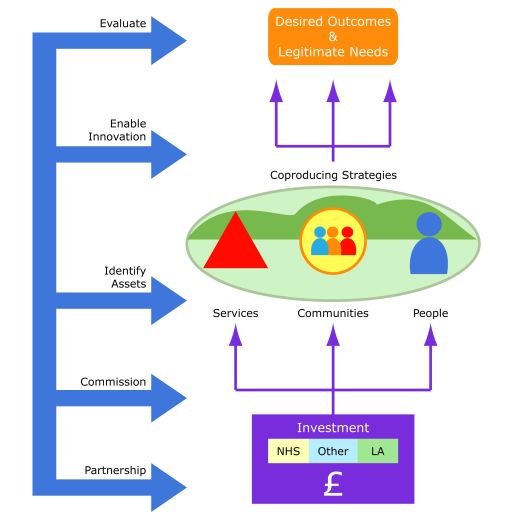

Localism will make sense if local communities are really part of the construction of decent local solutions. The key to this strategy will be to work with and enhance the local civil society:

This is not about a ‘Big Society’ it is about constructing local alliances and solutions that have the commitment of local citizens. Partly this means looking at what is already working local communities. Importing solutions will not work. Communities already have leaders and innovators - at every level - but they will often not have come to the attention of the public system and they may not even know their own capabilities.

Social justice demands building upon the capabilities of local people.

One local area cannot make these changes on its own. It will be important to build a powerful alliance of other communities who want to achieve real localism. It will be the shared learning and the development of a sense of wider movement which will enable local leaders to act with sufficient courage and clarity.

Ultimately a new policy model will be necessary; and this will also mean arguing for fundamental constitutional change. To achieve devolution in Scotland took real local action, bridge-building and debate. Attempts to impose regional structures from central government failed because the public suspected that these were just opportunities for new jobs for politicians and their allies.

Power will not be given back from the centre until new leaders emerge who care more about their local communities than party politics, their careers or honours and peerages. There has never been a better time to start building for real localism.

It can be guaranteed that, when we come to the next election, everybody will be talking about the need to shift power back to local communities. In times of austerity decentralisation becomes the default position. However it is likely that this will continue to be 'just talk'. If any of this talk is to become real then it is local communities themselves who must claim back their own authority, together with a fairer economic settlement.

The publisher is The Centre for Welfare Reform.

Real Localism © Simon Duffy 2012.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

Constitutional Reform, local government, Neighbourhood Democracy, England, Article