This article and film reviews the work of Simon Duffy on the topic of citizenship.

Author: Simon Duffy

It starts to feel like a kind of personal failure that I’ve been banging on about citizenship for more than 30 years and I still haven’t persuaded people that citizenship is the key to tackling the tremendous challenges we all face.

Refugees are turned away, incarcerated or deported; institutions, prisons and camps continue to blight the world; disabled people or anyone who is deemed too different faces daily prejudice and exclusion; the climate crisis and mass species extinction worsen; inequality grows and attacks on our public services continue. Perhaps most worrying of all is the declining standards in many of our democracies, and the growing tendency to authoritarianism and even neofascism. This is driving us into wars, while the threat of nuclear annihilation still hangs over our heads.

These are dark clouds. But light does still break through and so often it breaks through when individuals come together, without waiting for permission from the powerful. Ordinary people challenging injustice and trying to make change together. This is citizenship in action.

So I was really pleased to be asked to give this talk by the Citizen Network North America group who are leading the Need for Roots series, bringing together thinkers and activists who have been working to advance inclusion.

What follows is not a transcription of the talk, which you can watch above. Instead I have provided a kind of annotated bibliography, to pull together the most important of my own writings on citizenship and along with other writings that I think are relevant, useful and hopeful.

My own understanding of citizenship is entangled with the practical problems I’ve tried to tackle over the last 30 years. But my understanding of citizenship is rooted in some of the writings that inspired me as a child and as a student. Certainly three very influential figures for me were Nicolo Machiavelli, Hannah Arendt and Simone Weil.

Machiavelli might seem an odd source of inspiration. But Machiavelli is widely misunderstood and treated merely as a cynic. In fact Machiavelli was a republican, who was fascinated by the problem of reconciling the fact that the best societies were republics, where ‘the many’ were in charge, but so these republics would be corrupted and ‘the few’ would take over. His most important writing on this topic is not The Prince, but The Discourses. This book was probably the most influential in shaping my choice to study politics and philosophy at university.

Machiavelli N (1970) The Discourses. London: Pelican

At university I was very lucky to get the chance to study with Jeremy Waldron, and he introduced me to the work of Hannah Arendt. In my opinion she and Simone Weil are the two most important political philosophers of the twentieth century. Perhaps Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism has had the most impact on my own thinking, because she went deeper than most in trying to understand how Nazism, The Holocaust and the horrors of Stalinism developed. This book may not seem to be about citizenship, but it is, it is citizenship viewed through the lens of everything that erodes and corrupts it.

Arendt H (1986) The Origins of Totalitarianism. London: Andre Deutsch.

My own short book The Unmaking of Man is heavily influenced by my reading of Arendt.

Duffy S (2013) The Unmaking of Man: Disability and the Holocaust. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform.

I would also encourage people to read The Need for Roots by Simone Weil. This book, written as a kind of manifesto for Frances, during World War II, offers a different framework to political philosophy any other I’ve read. Some of it can seem bizarre, but it is rooted in a desire to find a framework where all human beings can flourish. Also a called a Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind, Weil understands that societies thrive when their members understand that it is their role to nurture, protect and improve themselves and each other.

Weil S (1987) The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind. London: Ark.

There are other books which shaped my early thinking. But I think these are probably the books that are most important to me and to which I can return and always find something new and useful.

All these writers have been influential in helping me think; but the demand to think came from my early work experiences. In 1988 I visited an institution where people with learning disabilities were incarcerated, and this inspired me to help people with learning disabilities move from institutions into the community, and so I got a job working in Southwark, in London, in 1990. As I began this practical work I also had the chance to read the works of two important thinkers and activists, Wolf Wolfensberger and John O’Brien.

Wolfensberger was the author of Normalisation and one of the leading thinkers behind the movement for deinstitutionalisation. He had developed a model for thinking about what was wrong with an institution and what was necessary to replace it, which was at first called normalisation and later Social Role Valorisation (SRV). This work is very powerful and has inspired important social change; however, while I took a lot from his writings, I also found some of it very uncongenial. This is not the place to examine the strengths and weaknesses of his model, but I never found myself capable of becoming a disciple of SRV and perhaps the fact that there certainly seemed to be a kind of Church of SRV was a turn-off for me.

Wolfensberger W (1972) The Principles of Normalization in Human Services. Toronto, NIMR.

Wolfensberger is well worth reading and some his later writings are very prescient on the emergence of eugenic practices. There is a full bibliography here: https://wolfwolfensberger.com/images/WolfWolfensberger/website/wolfensberger2011c-curriculumvitae-bibliography.pdf

On the other hand I found the writings and particularly the talks of John O’Brien, wonderfully inspiring. I had one talk of his on a tape recording, which I listened to again and again in my car. O’Brien and his allies didn’t talk about normalisation, they talked about inclusion. It really struck me that this idea, which while obviously idealistic, was rooted in a very real appreciation of what was important in life. It also struck me that this concept was entirely absent from my previous intellectual training and the ideal of inclusion fills an important gap in our intellectual tradition.

You can find a bibliography and other useful resources from John O’Brien here: https://inclusion.com/change-makers-resources-for-inclusion/john-obrien-change-makers-books-videos/john-obrien-books-videos/

I would also like to note that Inclusion Press, Judith Snow, Marsha Forrest, Jack Pearpoint and a range of other connected thinkers, have also continued to provide important food for thought. You can find Inclusion Press here: https://inclusion.com

The puzzle I faced as I reflected upon these ideas was that the ideals we talked about were often some distance from the reality of life for people living in the care services that were developed as the large institutions were closed. There was no doubt that life was ‘better’ now; but it was rarely as good as one might hope for. So I tried to think about what might make things better.

Perhaps, given my education, it is no surprise that the initial focus of my work was the fact that it seemed to me that what was primarily lacking in the lives of people with learning disabilities was power. Not only did people not have power, it seemed to me that few people wanted to talk about the fact that the system still had all the power. The system had moved people out of large institutions and made lots of changes in people’s lives, but it had never asked itself why it still had all the power, controlled all the money and shaped all the values and decisions around people’s lives. Challenging this assumption, both practically and intellectually, became the central work of my life from 1990 until 2009; that’s 20 years obsessed by one problem, for good or ill.

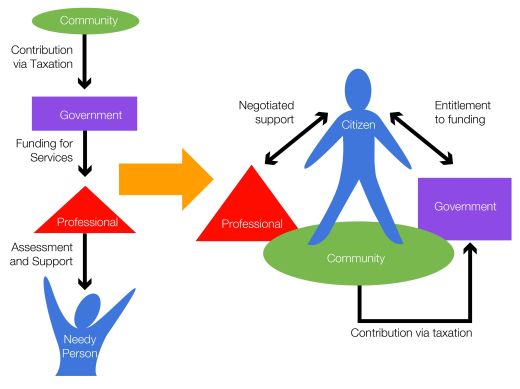

My first published writings on this topic were a series of articles in the Health Service Journal, which are not now available. But the basic outline of the problem and the solutions I pursued are set out fairly clearly. One concept that I still use and which is quite widely cited is the idea that we need to shift from the Professional Gift Model of services to a Citizenship Model of services.

I wrote about this in my 1996 book Unlocking the Imagination, which is available to read here.

Duffy S (1996) Unlocking the Imagination. London: Choice Press.

Duffy S (2014) Unlocking the Imagination: Rethinking Commissioning. 2nd Edition Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform

In fact much of what would later be used to develop models of self-directed support in England and my work at In Control was already largely sketched out in that book. However interest in that kind of systemic change was non-existent in 1996 and my work instead focused on the development of Inclusion Glasgow, and the establishment of other personalised support providers in Scotland. I remain very proud of this practical work, getting people out of institutions, one person at a time; not pushing people into group homes, day-centres or services, but designing flexible support in partnership with people and families. Work that wouldn’t have been possible without friends like Frances Brown and John Dalrymple.

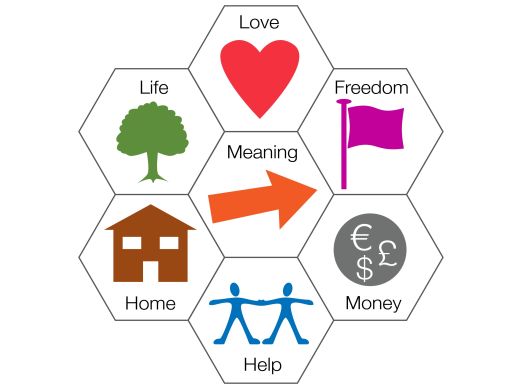

What struck me about this work was that much of it would be possible for any person or family if they had both control of their own budget and some good information about what was possible instead of the current service system. This is what led me to write the Keys to Citizenship, which was published in 2003. That book had two editions, but is now out of print.

First edition: Duffy S (2003) Keys to Citizenship: A guide to getting good support for people with learning disabilities, first edition. Birkenhead: Paradigm

Second edition: Duffy S (2006) Keys to Citizenship: A guide to getting good support for people with learning disabilities, second revised edition. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform

Wendy Perez and I hope to publish a new highly accessible version of the book in January 2023 and our 2014 article and the guide produced by Sam Sly and Bob Tindall are freely accessible.

Duffy S & Perez W (2014) Citizenship for All: an accessible guide. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Sly S & Tindall B (2016) Citizenship: a guide for providers of support. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform.

I continue to think that the Keys to Citizenship framework is useful. It is not just a way of organising a range of important practical suggestions and solutions. It is also a framework for thinking about how communities generate respect and status for all their members. For the challenge is not just to aspire to value everyone equally, or to make statements about the innate dignity of all human beings. The real challenge is to live together in a way that makes equal respect a fundamental feature of all our lives. People need the keys to citizenship, so that they can live in ways that others can respect. We need a society which makes it possible for everyone to live as an equal citizen. This requires both social and individual change.

I also wrote about this in the Journal of Social Work Practice and argued that citizenship was the proper goal of good social work.

Duffy S (2010) Citizenship Theory of Social Justice - exploring the meaning of personalisation for social workers, Journal of Social Work Practice Vol. 24 No. 3 pp. 253-267

I argued that Citizenship and an approach which looked at the objective factors which enhanced it was a better approach to thinking about how to organise support services than normalisation and so should be treated as the proper framework for designing supports for people with disabilities.

Duffy S (2017): The value of citizenship, Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, DOI: 10.1080/23297018.2017.1292147

I have also tried to take this idea of citizenship away from the specific problems of disability and social work into an exploration of the value of citizenship in political theory. In Citizenship and the Welfare State I argued that citizenship should be at the heart of our understanding of the welfare state and that its design need to change to reflect that fact.

Duffy S (2016) Citizenship and the Welfare State. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform.

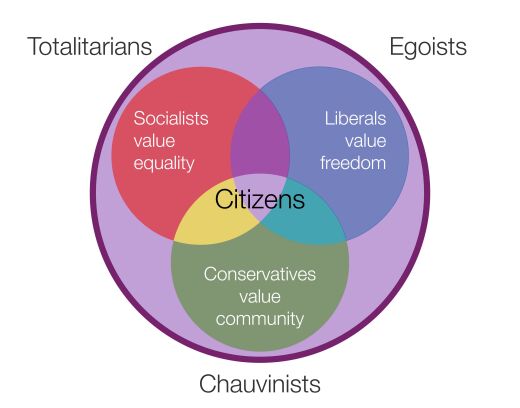

I also argued that current political ideologies (socialism, liberalism, conservatism) each contained a kernel of truth, but without a commitment to citizenship each becomes deformed into a corrupt forms of themselves (totalitarianism, egotism, chauvinism).

Further, in Love and Welfare, I argued that if we take the ideal of love, as it is understood in religious thought, seriously as a political ideal then its proper form would be a commitment to equal and active citizenship for all. I also used this essay to explore the value of Maimonides’ Eight Degrees of Charity, another framework that I’ve always found inspiring and relevant to an understand of citizenship.

Duffy S (2016) Love and Welfare. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform

Most recently I argued that true citizenship is not something that can properly be defined by the state or an elite, but that it was essentially an emancipatory idea open, to everyone.

Duffy S (2022) Citizenship and Human Rights in Fjetland, K. J., Gjermestad, A. & Lid, I. M. (Eds.) (2022). Lived citizenship for persons in vulnerable life situations. Theories and Practices. Scandinavian University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18261/9788215053790-2022-07

This is also an issue I explore in an upcoming publication, which is the write up of my 2019 Norah Fry Lecture Truth and Citizenship. For I think it is very important that we reflect on both the value and limitation of human rights. I argue that rights, human rights and disability rights are good, essential, but inadequate concepts. They need to be supplemented and supported by a commitment to citizenship. On their own they don’t motivate the sense of responsibility upon which rights depends.

In fact this links back to the topic of my PhD, which is the objectivity of morality. In my doctorate I argue that morality is real and that the different ways we have talking about it (duties, rights, virtues and goods) are all important to forming a good moral understanding. However the failure to recognise the special importance of duty is likely to dangerously distort our understanding of morality. There can be no rights, virtues or moral goods without the responsibilities which drive us to respect, honour and achieve them.

Duffy S J (2001) An Intuitionist Response to Moral Scepticism: A critique of Mackie’s scepticism, and an alternative proposal combining Ross’s intuitionism with a Kantian epistemology. PhD Thesis, Edinburgh University.

On a more practical level I have also tried to find ways to measure our capacity for citizenship and to understand the practical conditions necessary. This report on the work of Barnsley contains some interesting, if still undeveloped models:

Duffy S (2017) Heading Upstream: Barnsley’s Innovations for Social Justice. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform.

I would love to have more time to write. However, as ever, I feel like the priority is to try and bring about some of the practical changes we need to make citizenship for all a reality.

Of course the most important form this has taken is the development of Citizen Network and the conversion of the Centre for Welfare Reform into Citizen Network Research. With long-term friends and new allies we are seeking to build a global movement for citizenship which can bring people together working in different places on connected themes. We are connecting projects on self-direction, basic income, neighbourhood democracy and constitutional reform and trying to establish practical approaches to cooperation and communication to achieve the necessary changes.

One hopeful sign is that it feels like more people are starting to write about citizenship, from different perspectives. Perhaps the wind is starting to change.

Jon Alexander’s book, Citizens is inspiring and hopeful. Once an ad-man Alexander is arguing that we’ve been living through a time when the elites have treated ordinary people as consumers, pandering to our whims, offering up public services as products, pushing economic growth beyond the point of sustainability. But Alexander thinks the time of citizenship is upon us, and he shares a wonderful selection of stories of citizenship from around the world.

Alexander J (2022) Citizens. Kingston upon Thames: Canbury Press.

Another hopeful figure is Rutger Bregman, both of whose books I’d recommend. His most recent Humankind explores the myths we’re told about human nature and the way in which we are encouraged not to believe in ourselves, but to hand power to elites to govern over us. With fascinating examples from history and the social sciences Bregman argues that the path to citizenship is to have much more faith in our own capacity to solve our problems together.

Bregman R (2017) Utopia for Realists. London: Bloomsbury

Bregman R (2020) Humankind: a hopeful history. London: Bloomsbury

Another important thinker is Cormac Russell. Russell is building on the work of John McKnight and others from a movement for community development which is actually a close intellectual cousin of the movement for inclusion. These thinkers and practitioners have been exploring how democracy can understood, not though the lens of state power and public services, but through the lens of neighbourhoods and civil society. As he argues, there are untold riches available in the capacities of citizens, both individually and collectively, if we can organise to release those capacities. We must start by identifying our strengths, rather than allowing other people’s sense of our deficits define the way forward.

Russell C (2020) Rekindling Democracy, A Professional’s Guide To Working In Citizen Space. Cascade Books.

The last book I’d like to mention is Camila Vergara’s Systemic Corruption. This is, as it sounds, a harder and more chastening read. But it explores some of the most important challenges we face if all this talk of citizenship is going to be more than rhetoric. In a sense she returns to the questions that Machiavelli asks: Why, if democratic republics are so good, are they so rare and so easily corrupted? She then applies what we can learn from ancient and modern history to suggest we need to start organising very differently for forms of plebeian power. This kind of thinking will challenge the status quo and implies that there will be no transformation without work; but it offers a realistic assessment of the challenge. Not empty talk of revolution, but a real rebalancing of society to enable citizenship to take root.

Vergara C (2020) Systemic Corruption: constitutional ideas for an anti-oligarchic republic. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Happy reading, citizen.

The publisher is Citizen Network Research. 30 Years on Citizenship © Simon Duffy 2022.

Citizen Network, community, Need for Roots, politics, social justice, England, Article