Simon Duffy explores the challenge of moving solutions upstream and away from the institutionalised solutions into which resources are locked.

Author: Simon Duffy

The harm caused by Austerity is enormous and unjustifiable. In most cases it seems that public services have responded as one might expect, cutting support and increasing eligibility thresholds. Increased death rates for older people are just one symptom of this dreadful policy.

It does not justify Austerity however to note that some organisations and individuals have acted differently and have tried to identify solutions to the crisis that are progressive. For instance, a few leaders have recognised that in order to respond to this crisis they must engage citizens and communities in the effort to ensure social justice and well-being.

There is a compelling case for rethinking the relationship between the welfare state and its citizens. In fact even to make this point in that way is to make the point in the wrong way. The welfare state should not be distinct from us - it should be ours - our legacy to build on and to advance, requiring both our protection and our ongoing commitment (Duffy, 2016).

Nor must we be compelled to move from questioning the role that public services play to rejecting those services. Public services will continue to play a vitally important role in our society, both in providing vital support, often support that individuals and families can never provide for themselves, and also in providing leadership for the whole community to develop strategies for wider social change. It is important not to lose sight of the essential role of public services nor to minimise their importance in the search to engage citizen and community capacity.

What is really required is a new kind of partnership, public services will continue to play the lead role in:

However this still requires innovation in public services. In particular two kinds of innovation are necessary:

Unfortunately resources and practices tend to become institutionalised. Often the system’s centre of gravity lies in those responses which are often far from ideal or which are even damaging. For example, people can end up in prisons, institutional care units, care homes or acute hospitals, even though we know that there are significant risks associated with all of these kinds of services. However it becomes very difficult to move responses upstream, to promote the necessary innovations that prevent need or which allow people to meet their needs more effectively and more efficiently.

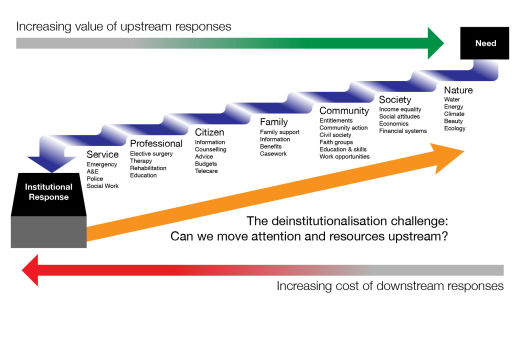

The solutions we find upstream are various and will develop in the light of the local context, but as Figure 1 suggests, they are all capable of reducing the demand for more expensive and less efficient solutions downstream:

Unless there is the right investment of time, money, creativity or self-discipline in these upstream responses then the result will be expensive, and often risky or violent, institutional responses. And once resources are locked into those institutional arrangements then they are very hard to shift again.

Once resources have been locked into hospitals, institutions, respite centres, prisons or care homes then there is a tendency for the system to meet needs by using those resources. The per capita cost may be high, but for the professional making the referral or placement the cost has already been met by a prior funding decision or by the fact that it is ‘someone else’ who meets the cost and manages any future risk. For instance, social workers often observe that the pressure to place someone in an appropriate service and so reduce any immediate risk they face can reduce their ability to work with citizens, families and communities to design better solutions (Rhodes, 2010).

There is also strong evidence that support can be offered to families so that women and children do not need to go to prison and that the cost of sending someone to prison is much higher than the cost of providing appropriate support. But the prison system is funded from Whitehall, so there is a weaker incentive for local areas to invest in these preventive measures (Hyde, 2011).

Figure 1. Moving investment upstream

Moving resources upstream will require a new kind of deinstitutionalisation. What, in Barnsley, is called inverting the triangle. Inverting the triangle means shifting the focus away from long-term and institutional provision and towards enabling people to stay healthy and well in their communities. The Barnsley model distinguishes:

Inverting the triangle does not just mean shifting resources and attention upstream away from institutional services, it means changing the whole philosophy of care. Everyone is assumed to be capable of managing their own care and support - but some people will need significantly more assistance or resources. Supporting autonomy and citizenship becomes a core value at every point in the system.

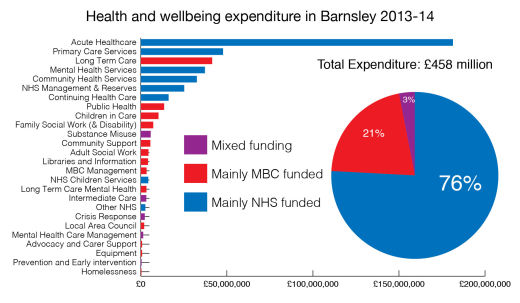

But the size of this challenge cannot be underestimated. Most expenditure for health and wellbeing is NHS expenditure (over 76%), and most of this expenditure is committed to acute services, with hospital and mental health services using nearly 50% of the total budget. Even community services and primarily health care services are primarily focused on employing professional staff. Very few resources are spent upstream or in engaging citizen and community capacity.

We get some sense of this by looking at the data for Barnsley as set out in Table 1 and Figure 2.

| Public service type: | Spend (£ millions): | Distribution: |

| Acute healthcare (NHS) | 181.33 | 40% |

| Primary care services (NHS) | 47.81 | 10% |

| Long Term Care (MBC) | 41.44 | 9% |

| Mental Health Services (NHS) | 37.24 | 8% |

| Community Health Services (NHS) | 32.57 | 7% |

| NHS Management & Reserves | 25.22 | 6% |

| Continuing Healthcare (NHS) | 16.15 | 4% |

| Public Health (MBC) | 13.57 | 3% |

| Children in Care (MBC) | 10.28 | 2% |

| Family Social Work (includes disability) (MBC) | 7.20 | 2% |

| Substance Misuse (MBC & NHS) | 5.75 | 1% |

| Community Support (MBC) | 5.55 | 1% |

| Adult Social Work (MBC) | 4.44 | 1% |

| Libraries and information (MBC) | 4.21 | 1% |

| MBC Management | 3.35 | 1% |

| NHS Children Services (NHS) | 4.33 | 1% |

| Long Term Care mental health (MBC) | 3.26 | 1% |

| Intermediate Care (MBC & NHS) | 3.19 | 1% |

| Other NHS | 2.66 | 1% |

| Crisis Response (MBC & NHS) | 2.31 | 1% |

| Local Area Council (MBC) | 1.99 | 0% |

| Mental Health Care Management (MBC & NHS) | 1.4 | 0% |

| Advocacy and Carer Support (MBC) | 0.77 | 0% |

| Equipment (MBC) | 0.75 | 0% |

| Prevention and Early intervention (MBC & NHS) | 0.45 | 0% |

| Homelessness (MBC) | 0.39 | 0% |

| TOTAL | 457.61 | 100% |

Table 1. Health and Well-being Expenditure in Barnsley 2013-14

Figure 2. Health and Well-being Expenditure in Barnsley 2013-14

It is also very challenging to make this shift when resources are tight - yet this is also when it is most important to make the change.

So it may be helpful to identify some key principles going forward:

One of the most interesting approaches for promoting innovation at the local level is the Local Area Coordination concept - first developed in Western Australia - but now being used in Scotland, England and Wales (Broad, 2012). This model involves embedding workers within small local communities - where they work with people who would be at high risk of needing costly or institutional services. Instead the Local Area Coordinator encourages people to connect and to solve problems by building on local resources.

This is not the only strategy for better prevention, early intervention, information and sign-posting. However it is a commitment to strategies such as these that will be vital. This is less about ‘commissioning innovation’ and much more about helping people craft local innovations - which make sense in their communities.

The critical question will remain:

Do we have the capacity to move resources towards better solutions upstream?

There will be no extra funding for innovation or change. Positive change will need to be transformative - it will need to make better use of existing funding. However this means changing how resources are used - this doesn’t just mean money - more fundamentally it is about people - the professionals currently working in the existing system. They must be engaged as part of the solution, they must themselves start to work upstream, and train others to do so. Otherwise the system will be locked into its current pattern.

Alakeson V (2014) Delivering Personal Health Budgets. Bristol, Policy Press.

Broad R (2012) Local Area Coordination. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Crisp N (2010) Turning the World Upside Down. London, RSMP.

Duffy S (2012) Peer Power. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Duffy S (2016) Citizenship and the Welfare State. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Halpern D (2005) Social Capital. Cambridge: Policy Press.

Health & Wellbeing Board (2013) Summary Financial Information.

Health & Wellbeing Board (2013) Joint Financial Planning and the Better Care Fund.

Health & Wellbeing Board (2013) Pioneers in Integrated Care and Support - Expression of Interest.

Hyde C (2011) Local Justice. Sheffield, The Centre for Welfare Reform.

Rhodes B (2010) Much More To Life Than Services. Peterborough, Fastprint Publishing.

Titmuss R M (1970) The Gift Relationship. London, George Allen & Unwin.

University of Leeds (2013) Stronger Barnsley Together - Proposal for Strategic Evaluation.

Wilkinson R and Pickett K (2010) The Spirit Level Why Equality is Better for Everyone. London, Penguin.

The publisher is the Centre for Welfare Reform.

Heading Upstream: Deinstitutionalisation & Public Service Reform © Simon Duffy 2016.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

local government, nature & economics, Neighbourhood Democracy, politics, England, Article