Simon Duffy outlines some of the important elements that need to be considered in order to develop welfare reforms in the spirit of justice.

Author: Simon Duffy

The 1945 welfare state was designed to reduce social injustice, and it was very effective in doing so:

These are important achievements and, as the UK continues to grow in wealth, technology and skill there is no reason to think that we cannot continue to build on this powerful and positive inheritance. But in the early years of the twenty-first century it is possible to identify two kinds of challenge that demand our attention:

The problem we face is to both build on the 1945 inheritance, with all its strengths and achievements, and yet imagine something that must go beyond and improve on that settlement, recognising we now live in different times. Yet this kind of change - change to the fabric of the welfare state naturally meets resistance.

People and professionals have many quite reasonable fears:

Introducing positive change in this environment is very difficult and there is always a danger that the meaning of the change gets lost. It is easy to be caught up in the latest craze, a new government programme or funding initiative. We lose sight of the real goal.

And that goal must be justice; and it is be worth reminding ourselves what justice really demands. In particular justice requires:

Arguably, the current design of the welfare system does not always manage to support this kind of holistic understanding of justice (Duffy, 2016a). Too often the welfare system falls back on a procedural or bureaucratised understanding of justice - treating people in a standardised way - rather than actually encouraging the creation of the kind of fair society we want to live in.

For ordinary citizens the fundamental foundations of justice are:

It is not just citizens who benefit from this kind of justice. Professionals, public bodies and civil society as a whole needs a framework of justice in which to thrive.

I have argued elsewhere that we can identify 3 interconnected strategies for promoting genuine reform in a spirit of justice:

1. Increase citizen control

When citizens directly control resources they can ensure that the solutions they identify not only meet their own needs but also increase the ability of themselves and of others to contribute to the community (Duffy, 1996). Direct payments, personal budgets and similar arrangements not only lead to better outcomes for the person they tend to:

2. Unlock community capacity

There is an enormous capacity for contribution locked in our communities but held back because of low expectations, a benefit system that penalises voluntary action and the lack of suitable roles and leadership (Duffy, 2016b). When this capacity is unlocked we see that people are willing to provide:

3. Move resources upstream

Public services have slipped into a role that is inadequate and insufficiently focused on empowering. Too many resources are lost in institutional services that waste the talents of both the people supported and the professionals supporting them (Duffy, 2016c). In the future resources and attention will need to move upstream:

But if these are the strategies for positive change and greater social justice what is the role of the wider public service system?

Currently the public service system, and the policies and laws which reinforce it, are still largely framed by the old model - where services are gifted to people by the state and it is the job of the state to manage that process by setting policy imperatives and then structuring, financing and regulating all those who are expected to deliver those services.

Services focus on their own goals. There is rarely any attention paid to the wider community’s resources or even the resources provided (or not provided) by other parts of the public sector. Each part of the system becomes a world unto itself. It is worth examining some of these other parts of the welfare system.

1. Citizen entitlements

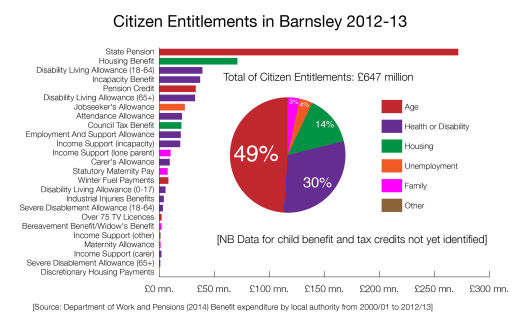

For example, the most important source of public funding in Barnsley is the pension and benefits system and yet this is rarely considered when discussing the health and social care systems. This system of citizen entitlements saw £647 million pounds invested in Barnsley through its citizens (see Table 1) from the DWP.

| Name: | Value (£mns.): | Kind: |

| Attendance Allowance | 20.7 | Disability or Illness |

| Bereavement Benefit/Widow's Benefit | 2.1 | Family |

| Carer's Allowance | 9.6 | Disability or Illness |

| Council Tax Benefit | 20.2 | Housing |

| Disability Living Allowance (0-17) | 5.7 | Disability or Illness |

| Disability Living Allowance (18-64) | 39.3 | Disability or Illness |

| Disability Living Allowance (65+) | 32.6 | Disability or Illness |

| Discretionary Housing Payments | 0.1 | Housing |

| Employment And Support Allowance | 19.6 | Disability or Illness |

| Housing Benefit | 71.1 | Housing |

| Incapacity Benefit | 37.2 | Disability or Illness |

| Income Support (incapacity) | 19.1 | Disability or Illness |

| Income Support (lone parent) | 10.4 | Family |

| Income Support (carer) | 2 | Disability or Illness |

| Income Support (other) | 1.3 | Other |

| Industrial Injuries Benefits | 4.18 | Disability or Illness |

| Jobseeker's Allowance | 23.3 | Unemployment |

| Maternity Allowance | 1.26 | Family |

| Over 75 TV Licences | 2.18 | Age |

| Pension Credit | 33.2 | Age |

| Severe Disablement Allowance (18-64) | 3.4 | Disability or Illness |

| Severe Disablement Allowance (65+) | 1 | Disability or Illness |

| State Pension | 271.8 | Age |

| Statutory Maternity Pay | 7.7 | Family |

| Winter Fuel Payments | 8.3 | Age |

| TOTAL | 647 |

Table 1. Benefit expenditure in Barnsley (2012-13)

This analysis shows that £647 million in benefits comes into Barnsley, but this is not even comprehensive, for it excludes tax credits and child benefit, which are now managed by HMRC. [It seems that a side-effect of the peculiarity by which benefits are now organised - divided between the HMRC and the DWP - means that we can no longer easily map the regional impact of some benefits. Taking separate tables from HMRC my estimate is that tax credits brought £127.88 mn. into Barnsley whilst Child Benefit brought in £46.1 mn. If anyone can point me to clear and coherent data on these matters I'd be very grateful.]

Overall the benefit system is also confused and stigmatising. It is estimated that about 10% of benefits go unclaimed (Duffy and Hyde, 2012). If people received their full entitlements then and extra £65 million would be available in Barnsley. The system also makes it harder for people to do paid work or to do the voluntary work of citizenship (Duffy & Dalrymple, 2013).

But the system is also intimately linked to health and wellbeing. As Figure 1 illustrates £195 million of the entitlements claimed in Barnsley are health or disability related (30% of all entitlements) and this figure is greater than all spending on acute medical care. However it is also noticeable that these health and disability benefits are particularly confusing and are broken up into at least 12 different funding streams.

Figure 1. Citizen Entitlements Barnsley

So this money is an important resource for disabled people and people who are in ill health, and it goes directly to people themselves, cutting out waste and inefficiency. However there are now plans to transfer Attendance Allowance to local government in order to subsidise the adult social care system. This is to move resources in precisely the wrong direction - away from people and into the system.

It is also noticeable that changes to citizen entitlements (called 'welfare reforms' but hardly improvements) are increasingly based on using private contractors, funded from Whitehall to run assessments and work readiness programmes. Instead of using existing health and social care resources to efficiently assess the system is wasting money on profit-making organisations. Money and expertise again moves away from the local and towards the central.

2. Local council spending

In addition local authorities control other important streams of funding, technically outside health and wellbeing, but which will have an important impact on their community. For example, the total expenditure of Barnsley Council is described in Table 2 and totals £665 million.

| Spend (£ mn.) | Income (£ mn.) | Net (£ mn.) | |

| Central services | 53.6 | 24.9 | 28.7 |

| Culture & related | 14.8 | 2.3 | 12.5 |

| Environment & regulation | 26.8 | 6.7 | 20.1 |

| Planning | 19.2 | 7.1 | 12.1 |

| Children & education | 268.4 | 227.0 | 41.5 |

| Highways & transport | 33.9 | 2.8 | 31.1 |

| Housing | 162.6 | 146.5 | 16.1 |

| Adult social care | 86.0 | 37.6 | 48.4 |

| TOTAL | 665.4 | 454.8 | 210.6 |

Table 2. Barnsley Council Expenditure (2012-13)

However it’s important to note that much of this funding is ring-fenced and is not under the direct control of Barnsley Council or the citizens of Barnsley. Most of the money spent on schools is defined and managed by the Department of Education, not by the local council. Funding for housing includes Housing Benefit which is also included in the benefit expenditure and is not controlled by Barnsley.

If we went further with this analysis it would be interesting to understand what other forms of public expenditure were being made in Barnsley:

On the basis of the estimates provided here:

It is also interesting to compare these figures to overall public spending in the UK, which is about £675 billion. If public spending were distributed evenly on the basis of population then we would expect to see public expenditure in Barnsley be equal to £2.5 billion. However, on the basis of my calculations above that figure is £1.7 billion, which means that there's about £0.8 billion unaccounted. Of course some of this may be legitimately being spent elsewhere or on services missing from this account. But this is a very large figure.

All of this raises profound issues about the centralisation of power in Whitehall and the opaque nature of public finances. The population of Barnsley is only a little smaller than the population of a small country like Iceland. Yet it has no significant control over its own resources nor does it seem to get a fair proportion of national resources. There is much talk of the possibility of radical devolution, but given that the Uk is the most centralised welfare state in the world it seems unlikely that this will be easy.

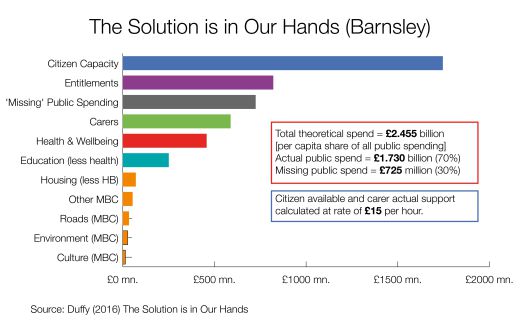

4. Total capacity

Whether or not Barnsley has been deprived unfairly of its proper share of public expenditure it is clear that there is still an enormous capacity within Barnsley itself, in the form of all those citizens who do provide care and support to others or in those who might be volunteering and contributing to the community in other ways.

By my calculations (Duffy 2016b):

These are crude estimates. Looking at all this data together Figure 2 provides an overview of the resources that a place like Barnsley has got available to it. And what these estimates indicate is that the potential for creating communities which are stronger, more nurturing and more just is very real.

Figure 2. Resources available in Barnsley

The centralisation of welfare spending within the UK is a complex problem with a long history. Given that it is perhaps not surprising that there are many overlaps between different funding sources or that responsibilities are sometimes unclear. In the long-run it might be helpful to explore with national policy-makers:

The supposed plan to devolve power to local communities may help. But much depends on important details of how the funding settlement is designed and what control Whitehall retains over the regulation and objective setting process. Past experience suggests that local power is hard won and rarely handed down from Whitehall without no strings attached.

Ultimately positive change is likely to be a mucky process. Local leadership will need to emerge and local leaders will need to collaborate to create the right conditions for coherent change. A new settlement will need to be negotiated between the local and the central, and this raises profound questions about our constitutional arrangements.

To end I just want to consider what some of the elements of local strategy might be for rethinking the meaning and organisation of the welfare state at a local level. Here are my suggestions:

The solution is in our hands. We can create a more just welfare system and more welcoming, vibrant and fair societies. But we need to look again at the resources available to us. For too long we've been fixated by given service systems and government controlled funding. We have the resources we need, but we must unlock them to ensure that people can give of their best.

Duffy S (1996) Unlocking the Imagination. London, Choice Press.

Duffy S (2014) Counting the Cuts: what the Government doesn’t want the public to know. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Duffy S (2016a) Citizenship and the Welfare State. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Duffy S (2016b) Calculating Community Capacity. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Duffy S (2016c) Heading Upstream: Deinstitutionalisation & Public Service Reform. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Duffy S & Dalrymple J (2014) Let’s Scrap the DWP. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Duffy S and Hyde C (2011) Women at the Centre. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Wilkinson R and Pickett K (2010) The Spirit Level Why Equality is Better for Everyone. London, Penguin.

The publisher is the Centre for Welfare Reform.

The Solution is in Our Hands © Simon Duffy 2016.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

health & healthcare, local government, politics, social care, Article