It's Our Community in Sheffield explored how to reform health and social care from the grassroots.

Author: Simon Duffy

Recently we ran It’s Our Community - a one day conference organised by Citizen Network and the Neighbourhood Democracy Movement - part of Sheffield’s Festival of Debate. For many it was the largest event they had attended since COVID and we managed to fill the Victoria Hall in Sheffield with people and groups from across the North of England (plus some friends and allies from elsewhere, including Ireland, Finland and Scotland).

We had some great feedback about the event, although I will still need many weeks to recover from the stress of organising it. It left me with even more respect for friends like Joe Kriss of Opus Independents who coordinated over 70 events at the Festival this year!

It’s Our Community is the name of our on-going project to rethink health and social care policy. COVID reminded us of two vital truths:

These are simple truths, but we often seem to forget them. Certainly, in England, although we’ve experienced many positive developments in health and social care over the last 50 years, we still struggle to remember these basic facts. There seem to be powerful gravitational forces pulling us away from the right path: money, bureaucracy and a fear of change.

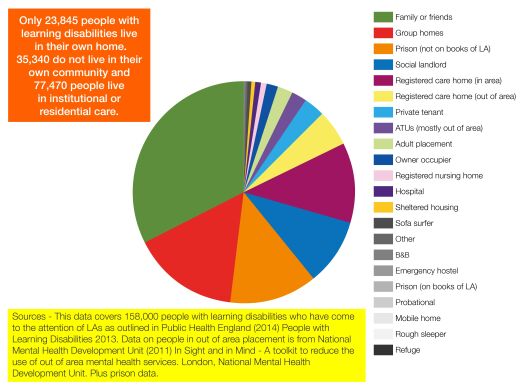

Perhaps the biggest positive change we’ve seen is the closure of the long-stay institutions. This has benefited many people with learning disabilities, mental health problems and older people. However what often replaced those large institutions was a tremendous growth in some different kinds of institutions. For example If we look at the data for people with learning disabilities in England today we discover that there are more people in institutions now than there were in the early 1970s (the peak period for institutional care). Many of these people are put in prison for minor offences.

Since 2010 the ongoing policy of Austerity has made this problem much worse. People face growing personal poverty, many families are in crisis, local community services have been stripped away and so people end up stuck in hospital, exported from their communities into care homes and increasing numbers of children are taken into ‘care’ (Saffer et al. 2018). The personal consequences of this policy are horrible and the economics is crazy. We are exporting people from our communities, wasting our money on careless care while failing to invest in the skills and talents of local people. The worst solutions absorb more of our money, making it even harder to invest in the right things (Duffy, 2019).

Alongside this we seem incapable of moving power and responsibility where it needs to be. Instead of encouraging communities to look out for each other, we rely on inadequate systems of regulation and control (Burton, 2017). Centralised services grow, local services are cut. Reorganisations always seem to further reduce meaningful democratic accountability. Typically, in cities like Sheffield, local neighbourhoods are given no voice and there are no truly local democratic structures by which citizens can control or scrutinise local services. This is not just bad for local people, it is also bad for the staff that work in these systems.

There have been some important victories, direct payments and, later personal budgets, have given some disabled people control over their own support and allowed investment in local people. There are good alternative models like the personalised support of iDirect, the networked support of KeyRing, micro-provision encouraged by Community Catalysts and the peer support enabled by groups like PFG Doncaster or Sheffield Voices. But these good practices are still too rare. The norm is for money to go into institutional care and often into businesses that extract profit, not just from the community, but from the whole country.

I stress the economic madness of this policy because I think GK Chesterton is right when he observes:

“…the optimist sees injustice as something discordant and unexpected, and it stings him into action. The pessimist can be enraged at wrong; but only the optimist can be surprised at it.”

I hope that we can increasingly come to understand that the policies we’ve been pursuing are not just bad, they’re irrational and doomed to failure. We must do better.

But what does better look like?

We are still gathering together much of the evidence from the day and we have further work to do in this project ahead of the next UK General Election. Our goal is to offer all political parties a better, more progressive vision for health and social care, and to see if we can address some of the long-standing social injustices faced by people receiving care and support and their families. However I will share some thoughts, based on what I heard at the conference.

Perhaps the strongest message, from across the whole event, was the determination to end the false hierarchy that suggests services and public authorities know best and that we—citizens and communities—must await permission to act. This is not about reversing the hierarchy. We need good public services and good government; but even when we have these good things that doesn’t mean that the role of the citizen disappears, for there are many good things that services can never and will never provide.

A lovely symbol of the abundance and freedom of citizenship was Suey, who is a fitness and dance instructor from Netherton. During the pandemic she went from street to street, encouraging people to get up and dance. This was not just good for health, Suey was bringing people together and creating community. In this same spirit Suey led the whole of the Its Our Community conference in exercises.

But do we talk about citizenship? Do we expect and encourage citizenship? Are we organised to support and celebrate citizenship? I don’t think so. Too often in the language of power we hear citizens being turned into patients, residents, service users, consumers or recipients; in other words, we turn the active into the passive, we don’t see the multiple gifts that each of us brings, instead we convert each other into an impossibly long list of needs waiting to be met.

Perhaps one thing we should stress in our work to grow flourishing communities is to remember that, if everyone is a citizen, this includes people working in the system. Even if the forces at work in the system seem to encourage paternalism and passivity the staff working in the system are still citizens too. They live in neighbourhoods which may or may not be flourishing; they know very well the limits imposed by system.

Awakening our sense of shared citizenship may help us all act with greater courage and urgency.

Some of the vibrancy of the day came from the people who turned up from different neighbourhoods in Wigan, Doncaster, Bury, Liverpool and Sheffield. These were people who were thinking about their places, their neighbourhoods, as real living and breathing communities - not just marks on a map.

This is the passionate force for change and justice that we are trying to support with the development of the Neighbourhood Democracy Movement. It is only if we pay attention to the truly local dimension of things that we can discover what democracy and equality really mean. If we leave everything to the system then everything will be decided by ‘other people’. Sometimes these people have good intentions; but sometimes they seem to be people who are only motivated by deep cravings for power, money or fame. Can we trust these folk with our communities? Do these folk know anything about our neighbourhood, our street, our neighbours or us? No.

Growing new patterns of community power isn’t easy. The UK is a highly class-bound society and power and decision-making has been largely left to a narrow elite who attend the same schools and universities. Although the UK calls itself a democracy it has set the bar for democracy very low indeed. As Andy Burnham, Mayor of Greater Manchester told us recently, at our Basic Income in the North conference, when he was in government he found that most of the big decisions were made by about 75 people in Whitehall. Is it surprising that so many communities feel politics and politicians are irrelevant to them?

The future lies in real democracy. People coming together, thinking, talking, deciding and acting together. This is what democracy means and it doesn’t require us to vote for politicians. When researching the reforms that Barnsley have been leading for the past decade one of the biggest messages from citizens was that they were turned off by party politics and that they didn’t want party politics anywhere near their local communities (Duffy, 2017a). This is an important message.

We’ve got a long way to go. Currently many neighbourhoods have no structures to help people come together. Many are not even recognised as real places by the system, even when everyone in that community knows that their community is real. So maybe the first step is for us all to start talking about our neighbourhoods, organising around them, gathering people, information and challenges and starting to find solutions that build on the passions and strengths of our neighbourhoods.

For instance, for a typical neighbourhood of 4,200 amazing, diverse and talented people there is:

Do we feel those resources are really being used to best effect?

What strikes me about this is that if we start thinking about care as something that happens at a neighbourhood level then very little of what we currently do makes sense:

A flourishing community is a place where we invest in each other. We learn the skills we need to look after each other, to bring up our children and to take care of each other as we get older. A flourishing community must be an inclusive community where everyone is welcome, nobody’s skills and gifts are neglected and where we help everyone to live a life well-lived.

Personally, having previously put a great deal of effort into giving life to the idea of personal budgets, my attention has now shifted. I still think personal budgets are really valuable, but even more important is peer support. I think people gain more from being connected to other people, to learn, to share and provide mutual support, much of which can never be covered by a personal budget.

I’ve seen the power in peer support in many different places:

This kind of peer support is born out of shared experiences, often experiences of injustice, ill health or exclusion. But it liberates people because it connects people at a deeper level. Peer support is not a transaction where one person does good to anther person; peer support changes both people, it creates a real experience of equality and it helps people understand their gifts and value.

It is also extraordinarily productive. The data we gathered in Halifax and Doncaster demonstrates that peer support does things that public services can never do on their own and can never purchase from anyone else. Peer supporters also creates a collective understanding of what is really necessary. People build on their lived experience, but they also gain the freedom and strength to say what really matters. Peer support keeps us honest and it must be central to how things change.

The conference also shone a light on the great work that some services are doing to support people to be citizens. Friends from Imagineer, Lives Through Friends, Radical Visions and New Prospects all shared stories of how thoughtful well designed support is support that connects people back to family, friends and community. This work is still not widely understood; too many services are described as ‘community services’ but their consistent feature is that they make community contribution harder.

A great example of work to support citizenship is provided by iDirect, who use Individual Service Funds and carefully tailored support to enable people to leave the kind of institutional care associated with scandals like Winterbourne View (Fitzpatrick, 2010; Smith & Brown, 2018). Hatty’s story for example shows the importance of really listening to people and families and supporting people to live in a way which fosters the relationships that really matter. With the right support, and despite having severe schizophrenia, Hatty lives successfully in the community.

Kate Fulton, one of the founders of Citizen Network and CEO of Avivo in Western Australia also shared some of the innovative work they are doing to treat staff as citizens, to reduce middle-management and move support staff into self-managing neighbourhood teams (Basterfield & Fulton, 2019). This model builds on the work of pioneers like Buurtzorg, but takes some of these principles even further.

Some of our recently published research on the NHS also suggests that health professionals are craving to reconnect to community. A smaller scale NHS, linked to real communities, is also the pathway to less hierarchical management, less bureaucracy and more joy in your work (Baksi et al. 2023). A recent policy proposal from Tim Keilty describes clearly how we can stop the madness of sending people away from their communities because of so-called "challenging behaviour" (Keilty, 2022).

Perhaps also we should be learning from developments like Nuka, in Alaska, which transforms the power relationship between community and healthcare professionals (Harrison, 2015). If public services are really going to serve the public shouldn’t we we exploring how we make them accountable, not to Whitehall, but to the communities they exist to serve?

We were lucky to be joined at the event by people working in local government and the NHS who are really trying to make significant change happen. Places like Barnsley and Doncaster are on a journey to discovering what the role of government really needs to be. We’ve got a long way to go with decades of harm to undo; but progress is possible.

In my opinion one of the key policies that needs to change is the extensive use of procurement and competitive tendering to spend our money. The current system was developed by the Thatcher government and after 40 years we now have all the evidence we need to know it doesn’t work (Duffy, 2017b). Current procurement systems:

We need to examine the basic architecture of public services in the UK and ask ourselves what we can do to promote citizenship and community. Good government would put much less emphasis on doing things for people and much more on learning what is working and helping everyone to do better.

If we start to treat each person and each community as an innovator and then we explore how to network their learning to speed up positive change we will do much more to tackle social problems than if we keep imposing one model on every person and every community. Embracing our diversity is the key to respecting our rights as equal citizens.

We live in confusing times. We can see that so much is wrong, and yet we also know that so many of the solutions we need are in reach. But mostly the powerful seem to be saying “Hold tight, don’t worry, trust us.” Yet then they seem to be incapable of taking any of the actions demanded by the seriousness of the challenges we face.

But for those of us who want to see change there are several paths to take.

We can dig deeper and work out what to do, right now, in our neighbourhoods or in the peer groups we are part of. The good news is that this will always be fruitful and that there are always things we can do. So we must do this.

We can also share a vision of a better world: tell stories, share examples and build practical structures to help us do all that work better, faster and stronger. This is what we are trying to do at Citizen Network and within the Neighbourhood Democracy Movement—get stronger by getting connected and getting organised.

But my personal hope is that we can also tackle some of those systemic problems that hold us back. I think there are politicians, local government officers, doctors, administrators, teachers and many more public servants who have not forgotten that they are citizens too. Perhaps working with them we can start to turn away from the failed solutions of the past and start to invest in people and in community. This could make the work of citizens so much easier.

In the coming months I hope we can do more to make some of these better paths a little easier to see and move along.

Baksi A, Sinha A & Singhal P (2023) Health Care Services In Crisis. Sheffield: Citizen Network Research

Basterfield S & Fulton K (2019) Rethinking Organisations. Perth: Western Australia individualised Services

Burton J (2017) What’s Wrong with CQC? Sheffield: Citizen Network Research.

Duffy S (2017a) Heading Upstream: Barnsley’s Innovations for Social Justice. Sheffield: Citizen Network Research.

Duffy S (2017b) The Failure of Competitive Tendering in Social Care. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform

Duffy S (2019) Close Down the ATUs. Sheffield: Citizen Network Research.

Duffy S & Hyde C (2011) Women at the Centre. Sheffield: Citizen Network Research.

Duffy S (2021) Growing Peer Support. Peer-led crisis support in mental health. Sheffield: Citizen Network Research.

Fitzpatrick J (2010) Personalised Support: How to provide high quality support to people with complex and challenging needs - learning form Partners for Inclusion. Sheffield: Citizen Network Research.

Harrison S (2015) Relationship Based Care In Action. Sheffield: Citizen Network Research

Keilty T (2022) Building the Right Support. Sheffield: Citizen Network Research

Mahmic S & Janson A (2018) Now and Next: an innovative leadership pipeline for families with young people with disability or delay. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform.

Saffer J, Nolte L & Duffy S (2018) Living on a knife edge: the responses of people with physical health conditions to changes in disability benefits, Disability & Society, 33:10, 1555-1578 DOI: 10.1080/09687599.2018.1514292

Smith S & Brown F (2018) Individual Service Funds: A guide to make self-directed support work for everyone. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform.

Vidyarthi V & Wilson PA (2008) Development from Within. Herndon: Apex Foundation.

The publisher is Citizen Network Research. The Path to Community © Simon Duffy 2023.

Citizen Network, community, Inclusion, Neighbourhood Care, Neighbourhood Democracy, social care, England, Article