David Towell reviews Stephen Unwin's book examining changing attitudes towards people with learning disabilities.

Review of Beautiful Lives by Stephen Unwin

Reviewed by David Towell

Stephen Unwin is a scholar, writer and theatre director - you might say an expert with words. Stephen's son, Joey, now a young adult, is said to have ‘severe learning disabilities’, communicates a lot not least with his father, but doesn't have much use for words, still less books like this one dedicated to him. The juxtaposition between these two ways of being in the world provides one driving force for this book (also available in an easy read format).

The text is multi-layered, exploring the personal, the historical and the political...and their connections. Unwin's success in life has been characterised by high intellectual achievement. Getting to know his son for whom this is not going to be so important raises fundamental questions then about what is important: his title invites us to think afresh about different kinds of beautiful lives. This is the personal.

But Stephen is a scholar with a deep interest in literature. He had the energy to locate this question within a historical study of how societies (mainly in the UK but also in North America) have understood ‘learning disabilities’ and with what consequences for the people so identified. This is a complicated story summarised in his sub-title - how we got it so wrong. He argues forceably that in 2025 we are still getting it so wrong!

In turn, this leads to the political: what is to be done? What values and vision might better motivate future progress? How in the second quarter of the 21st Century can we achieve the radical social changes required to enable all of us to share positively in our common humanity? Understandably responding to these questions remains work in progress.

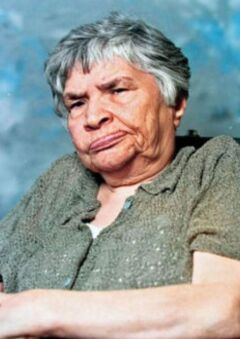

Judging by all the testimonies to this book, there is going to be no shortage of reviews. To make mine distinctive, I have elected to provide a commentary grounded in my personal experiences and more significantly, those of my sister Pat (pictured) - who like Joey never found much use for words. Pat's story started earlier but as an introduction, let me tell you about three days in May 1945. On the 8th May, we celebrated the end of the WWII in Europe and began a massive programme of national renewal. On the 10th, I was born and in due course became a major beneficiary of this post-war reconstruction. On the day in between, Pat - then aged eight - was admitted to institutional care, where she was to remain for 51 years.

I have told my version of our story in a book Brian Rix edited to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the family advocacy organisation, Mencap. My focus was on how her experiences and my experiences of her helped to inspire the social movement that sought the closure of institutions and a life of equal citizenship for all disabled people: in Unwin's terms, making the personal political.1 The goal of this movement was summarised in the slogan An Ordinary Life. I have told this story too.2 Pat, through childhood illness, acquired what were described as ‘profound disabilities’. As was the custom at the time, when her brother arrived, our parents were recommended to give up the ‘burden’ of her care to the state. Thus began her very long institutional career including many years in two of the places Unwin discusses, the Royal Earlswood and Normansfield (by then renamed) ‘hospitals’. It took far too long but in 1997 the latter was closed and she moved to an ‘ordinary house in an ordinary street’ (technically a ‘staffed group home’) with five other Normansfield residents, where she lived for the rest of her life. At the age of sixty, she had her own bedroom for the first time. Her photo above was taken by a professional photographer whom the staff commissioned as part of celebrating the new home. Pat was not into selfies and she is not posing here: nevertheless it conveys some sense of the dignity, tranquillity and attentiveness that she brought to later life.

Let's move to the wider history. ‘History of what?’ you ask. Ambitiously, Unwin starts this exploration in ancient Greece and Rome. In truth however, we don't know too much with certainty from these times and indeed for many of the following Centuries where typically people with ‘learning disabilities’ didn't seem to attract much interest. But it is more complex than this. I keep putting this terminology in inverted commas because it is both a recent innovation (the relevant U.K. 1971 White Paper was called Better Services for the Mentally Handicapped; the famous 1944 Education Act made provision for students who were ‘educationally subnormal’); ‘learning disability’ seems to be mainly a British invention and even here people so labelled tend to prefer ‘learning difficulties’. They are also likely to remind us to ‘Label jars, not people’.

In North America, ‘developmental disabilities’ and ‘mental retardation’ are commonly used instead. The United Nations (notably in the 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, UNCRPD) refers to ‘intellectual disabilities’. Words matter... and even terms initially adopted with reforming intent may become imbued with negative connotations often imported from earlier times. Unwin draws our attention to the use of the word 'idiot' in modern parlance. Our North American friends campaign vigorously against use of the ‘R word’.

These words are also located in wider disciplines. For a couple of Centuries now medicine had taken an interest in ‘learning disabilities’ and even though these are not illnesses, the ‘medical model’ has typically identified the problem as some kind of ‘deficit’ in the person. This is clearer when we consider an alternative view developed here by Mike Oliver and colleagues, usually called the ‘social model’. This identifies difficulties experienced by disabled people as mainly arising from barriers in the way society is organised: the 'treatment' is to remove the barriers. The UNCRPD follows the latter approach in asserting that universal human rights require that state parties remove the barriers and improve the support for disabled people so that they enjoy these rights on an equal basis with others.

Viewed over a longer time perspective, as Unwin skilfully does, we also need to explore the ways people are described and regarded in their social, cultural and economic contexts. Looking back over the last two Centuries and more, he identifies four main currents in how our culture has understood and valued people with ‘learning disabilities’, each summarised in a single word: Innocents, Menaces, Humans and Citizens. As these words imply, this is by no means a history of steady progress.

Going back to the 18th Century, there was some acceptance of ‘Innocents’ in their communities and some compassion for their poverty. Unwin quotes a poem by Wordsworth (1798), The Idiot Boy, which offers an affectionate portrait of a young man with no speech who nevertheless is capable of learning and contributing; most importantly he is the focus for strong maternal love. Of course, Wordsworth was a romantic poet.

This spirit of acceptance was badly disrupted however by what followed. The next two Centuries were full of social upheaval driven by the industrial revolution, the growth of capitalist production and new currents in science and philosophy. As a consequence, the ‘idiots’ I just described were increasingly regarded as a ‘social menace’, needing to be segregated from society and stopped from reproducing. In particular, Darwin's insights into evolution were twisted into misleading genetics and a eugenics movement that sought to protect the strength of the 'race' from dilution. Unwin reveals a surprising number of our national leaders had eugenic sympathies well into the 20th Century.

Thus began a period of rapid institution building in Britain (for example, required by the 1808 County Asylums Act and the 1886 Idiots Act) so that every County had its ‘pauper lunatic asylum’ and increasingly some of these began to ‘specialise’ (I use this word loosely) in people with ‘learning disabilities’. Normansfield was one of these and certainly began with a paternalistic but caring philosophy. (There is still an elegant Edwardian theatre on its site.) However there as elsewhere - and also well into the 20th Century - growing numbers of residents and policy neglect generated a tragic decline in standards, finally brought to public attention by a series of scandals and resulting public inquiries in the 1970s. Normansfield was also the focus for one of these. If Pat could speak, she would have a very interesting - and disturbing - story to tell.

As I say, Unwin uses Humans and Citizens as key words for his account of developments since 1945. In the Humans section, he seeks to show how new ideas and new practices challenged the history of treating people as less than fully human. In Citizens, he goes further in the recognition that people with ‘learning disabilities’ share the same human rights as all of us. At the same time, he makes clear that neither the eugenics nor the scandals have yet gone away.

In the event, the population of people sent away to institutions continued to grow up until the 1950s, peaking in England and Wales at nearly 60,000 - many in places housing 1,000 residents or more. (Of course, this was only a small proportion of the million or more people identified as learning disabled, the great majority of whom continued to rely mainly on family support. Accordingly it is still very common for parents in later life to struggle with the question, ‘What happens when we are gone?’) The reformers - the An Ordinary Life movement being an important example - aspired to ensure that everyone could live with dignity and in the conditions in which they could thrive as family members, students, neighbours and members of their local communities. Unwin identifies many of the leading innovators and their work; surely there were many more including very many who were essential to making things happen locally.

Of course, radical change needs public pressure and this period saw (in 1946) the formation of the family advocacy organisation that became Mencap and the emergence (in the 1970s) of self-advocacy groups in which people with ‘learning disabilities’ came together to rightly proclaim ‘We are People First’. At the turn of this Century (2001, i.e. 30 years on from the Better Services White Paper), the New Labour government was persuaded to produce a fresh statement of national policy, Valuing People, which sought both to learn from, and generalise the progress made since 1971.

Coming up-to-date, Unwin looks more closely at the extent of progress, for example in relation to education, health, housing, social care and employment, concluding that in contemporary Britain we are still falling way short of these policy intentions; indeed, that in the light of austerity, social division and the pandemic, the lives of people with ‘learning disabilities’ may be getting worse. One very striking statistic speaks to this assessment: their life expectancy on average remains 14 (men) - 18 (women) years less than their peers.

The fifth part of Unwin's book comes to the crunch: what is to be done? He uses the book title for this section, Beautiful Lives. I think we know that achieving radical change requires, at its simplest, a vision of a better future (and powerful arguments that justify this vision), a system-wide strategy (informed by a compelling theory of social change) and wide public support.

More than 40 years ago, we adopted An Ordinary Life as a slogan to drive our agenda (of course, recognising that very many people, Pat included, were a long way from anything close to this description). This phrase was both a simple definition of desired outcomes in people's lives and a description of the conditions that would make these outcomes possible.

An Ordinary Life as a vision has recently been re-energised by a family advocate, Tricia Nichol, who has upgraded the slogan, thinking of her own children, to Gloriously Ordinary Lives. Self-advocates and families now work together with professionals in a national advocacy association, Learning Disability England. They too have a vision expressed as the Good Lives Framework. And other important innovators (Wendy Perez and Simon Duffy) have recently published Everyday Citizenship, based on Wendy's life experiences.3 The global association of family organisations like Mencap is called Inclusion International.

To these variations on a theme, Unwin has added Beautiful Lives. Of course it is inspired by his positive experience of Joey and the wish to honour his individuality, joyfulness and free spirit. But he also wants to establish this as a broader goal:

I want people with learning disabilities to be able to live how they want, supported where necessary, but autonomous wherever possible, liberated at long last from labels and categories, free, even, from the very identity of 'learning disability' itself. They should be able to pursue their own 'beautiful lives' in whatever way they want, safe, happy and free.

I think that the An Ordinary Life activists would be happy with this direction of travel although I have an open mind on the most useful formulation for our times.

The complementary question is about ‘how?’. Unwin offers at least a partial account of why we are still getting things so wrong. As an expert in culture, his central idea is that our society privileges (what passes for) intelligence and this discriminates against those less endowed in this dimension. (The distinguished American philosopher, Michael Sandel, has written a much wider critique under the title, The Tyranny of Merit. Its subtitle is What's Become of the Common Good?) Clearly also, capitalism privileges (what passes for) productivity and self-sufficiency. I read this analysis as Stephen Unwin's invitation to all of us who share his vision to come together in a revitalised movement for radical change.

Let's return to my sister, Pat. She died in 2012 at the age of 75. At her funeral, we played Delibes’ Flower Duet. Staff supporting her said she loved this. I don't know how they made this discovery but the music is indeed beautiful. Pat had a machine that projected coloured lights in her bedroom. We used this projector in the church so we could all share something else she loved. Most impressive, more that eighty people showed up to say good-bye. Many had been paid to support her. Of course, she had never spoken to any of them. But something about the tranquillity and attentiveness you see in the photo had brought us all together to celebrate her humanity. Everyone belongs.4

1. David Towell Brothers and Sisters as Change Agents in Brian Rix (ed.) All About Us. Mencap, 2006.

2. David Towell Towards An Ordinary Life: Insights from a British story of social transformation, 1980 - 2001. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 2002. 1-9. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bld.12454

3. Wendy Perez and Simon Duffy Everyday Citizenship: Seven Keys to a Life Well Lived. Red Press, 2024.

4. The Belong Manifesto Beyond Words, 2018. https://www.booksbeyondwords.co.uk/belong-manifesto

The publisher is Wildfire. Beautiful Lives: How We Got Learning Disabilities So Wrong © Stephen Unwin 2025

Beautiful Lives Review © David Towell 2025

Deinstitutionalisation, Inclusion, intellectual disabilities, England, Reviews