The journey away from the institution demands we think more deeply about the world we need to create.

Dr Simon Duffy gave this keynote speech in Barcelona at the 28th Annual Forum of FEDAIA (Federació d'entitats d'atenció a la infància i l'adolèscència) in 2024. In this talk he explores the forces that created institutional thinking and structures and the importance of thinking deeply about how to reverse these forces today.

The individual and groupings of people, have to learn that they cannot reform society in reality, nor deal with others as reasonable people, unless the individual has learned to locate and allow for the various patterns of coercive institutions, formal and also informal, which rule him. No matter what his reason says, he will always relapse into obedience to the coercive agency while its pattern is within him.

Idries Shah

It is an honour to be here in Catalonia - a place that is well known as a global innovator in care and human rights - thank you for inviting me to speak to you.

For me, it is particularly exciting because you are thinking about deinstitutionalisation in new ways, in deeper ways and across many different fields. This is important work that will have a global impact. The energy for deinstitutionalisation, which emerged in the 1960s, has died down in many parts of the world. This is not because we’ve solved the problem of the institution. Sadly, in many places, we’ve settled for solutions that are not good enough. So thank you for taking on the challenge. For working on the bigger changes, we need.

This work is not just about care. It is the work we need to do to face many of the environmental, social, economic and democratic crises of our time. If we can work out how to live as equals, working together to ensure everyone can participate, contribute and grow, then we will equip ourselves to face these other big problems.

The image below is my local institution: Ecclesall Bierlow Workhouse. This is a picture from the 1840s a few years after this Workhouse was built. I live about 200 metres further down the hill. And the hill is important because the Workhouse was built on the hill of industrial Sheffield - the city that invented stainless steel - this picture makes the Workhouse look very pretty. And it has a grand exterior. But it was used to threaten the workers of Sheffield - this is where you go if you lose your job, lose your parents, become too disabled, ill or old to work. Inside the Workhouse it was designed to be miserable - this was all built into the 1834 Poor Law - to make sure nobody would be tempted to stop working.

Other kinds of institutions were also being invented in the early nineteenth century. For example, Lisa Appignanesi, in her book Mad, Bad and Sad - her history of women’s experience of psychiatry - writes:

“Indeed, in 1826, when national statistics began tone available, under 5,000 people were confined throughout England out of a population of some eleven million. This is a mere handful if one considers that by 1900 the beds in just two London asylums, Colney Hatch and Hanwell, numbered 4,800, and the figure of public asylums nationwide was 74,000.”

And this growth didn’t stop with the nineteenth century. For people with intellectual disabilities, the peak period for the institution was 1970.

We know that this isn’t how society should be. But what should we be doing instead?

The problem is that when we talk about deinstitutionalisation - focus is a obviously negative. De - institutionalisation - means we want to stop doing institutionalisation. So what is actually wrong with the institution? If we understand this we can begin to work out what we really need to be doing instead.

One of the confusing things about talking about deinstitutionalisation - is that the word institution is actually a word that carries both a very positive and a very negative meaning - at least in English.

The Latin root word is statuere and it means to establish, create, decide and to lift up or erect. So an institution is something that we’ve created, built up or erected. In general, to create an institution is not a bad thing. Human institutions are an important result of human creativity and our social development. There are many good institutions.

When we talk about deinstitutionalisation we are not talking about all institutions, we are talking about a special group of institutions: for example, care homes, special hospitals, asylums, prisons, concentration camps and worse.

And if we think about what makes these institutions unusual then I think it is primarily that these institutions are anti-freedom:

In fact, as the poet Joseph Brodsky - who had been institutionalised by the Soviet state put it:

…in prison at least you know where you stand. You have a sentence - till the whistle blows. Of course, they can always tack on another sentence, but they don't have to, and in principle you know that sooner or later they're going to let you out, right? Whereas in a mental institution you're totally dependent on the will of the doctors…

So if we know that these kinds of institutions kill freedom, let’s assume that freedom is one of the essential things we need to support. What follow is one story of what that can mean in practice.

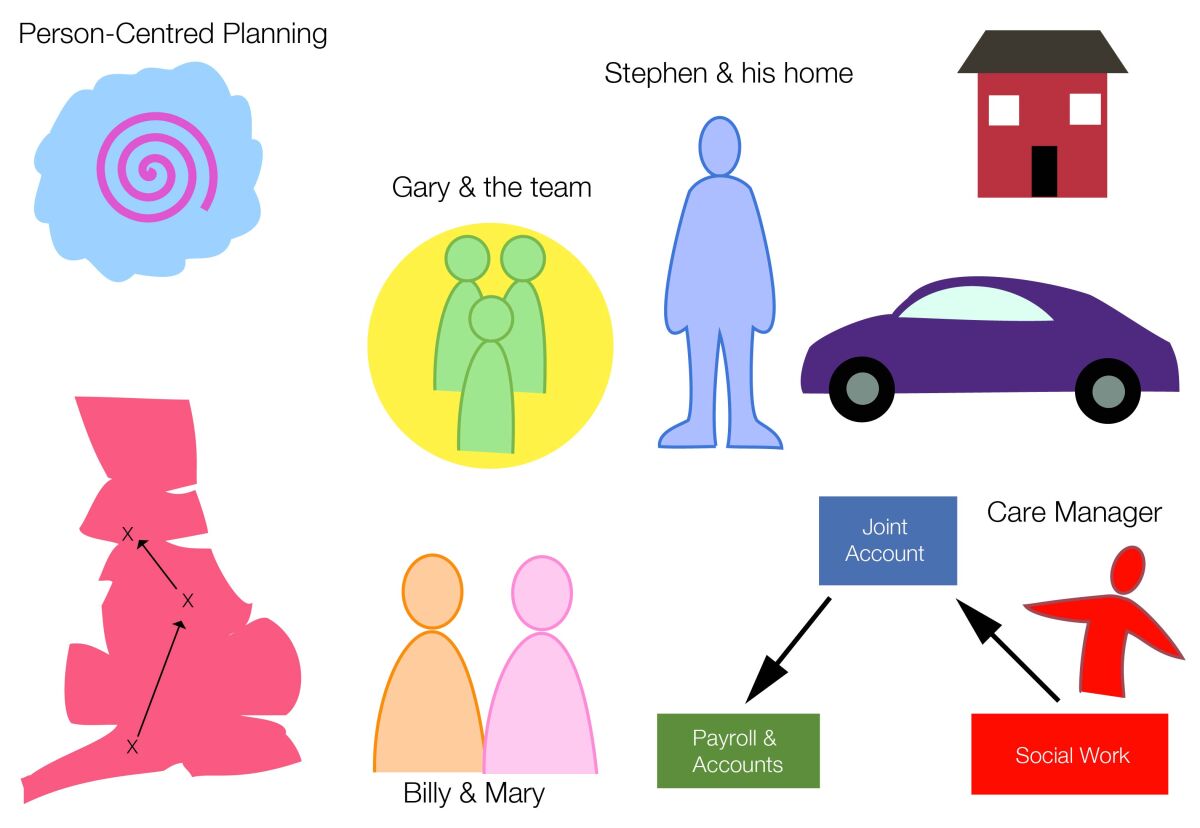

I want to start with a story from my personal experience. During the 1990s my life was largely dedicated to helping people with intellectual disabilities leave institutions, build their lives in community and take more control over their own support. Stephen’s story is typical both of how institutionalisation continues and what better alternatives look like. Stephen comes from Scotland and has autism and he didn’t cope well with the school system, so he was excluded. The only alternative specialist school was hundreds of miles away, in the South West of England. When his school years came to an end the private business which ran the his school then proposed that he move to a college in the North of England - in fact not far from where I live today. All of this was paid for by the Scottish Social Services Department where Stephen came from and where his family still lived.

But Stephen was lucky. His Mum and Dad visited the college and complained to the Social Services Department that the place where Stephen lived was an institution. This service cost £150,000 per year (and that is the 1999 price). They demanded Stephen return home.

At the time I was living and working in Scotland and leading efforts to create a system called self-directed support - that means people controlling their own funding - or in the case of people like Stephen - working with the people who loved the person the most. In his case this was Mum and Dad, and also his brother, Gary. In fact Gary had moved with Stephen and got a job at the residential school where Stephen lived, so he could learn about autism and make sure his brother was okay.

I suggested that the family be given a budget - 50% of what the institution was spending - and the freedom to design support that would work for Stephen. In the end this means that Stephen:

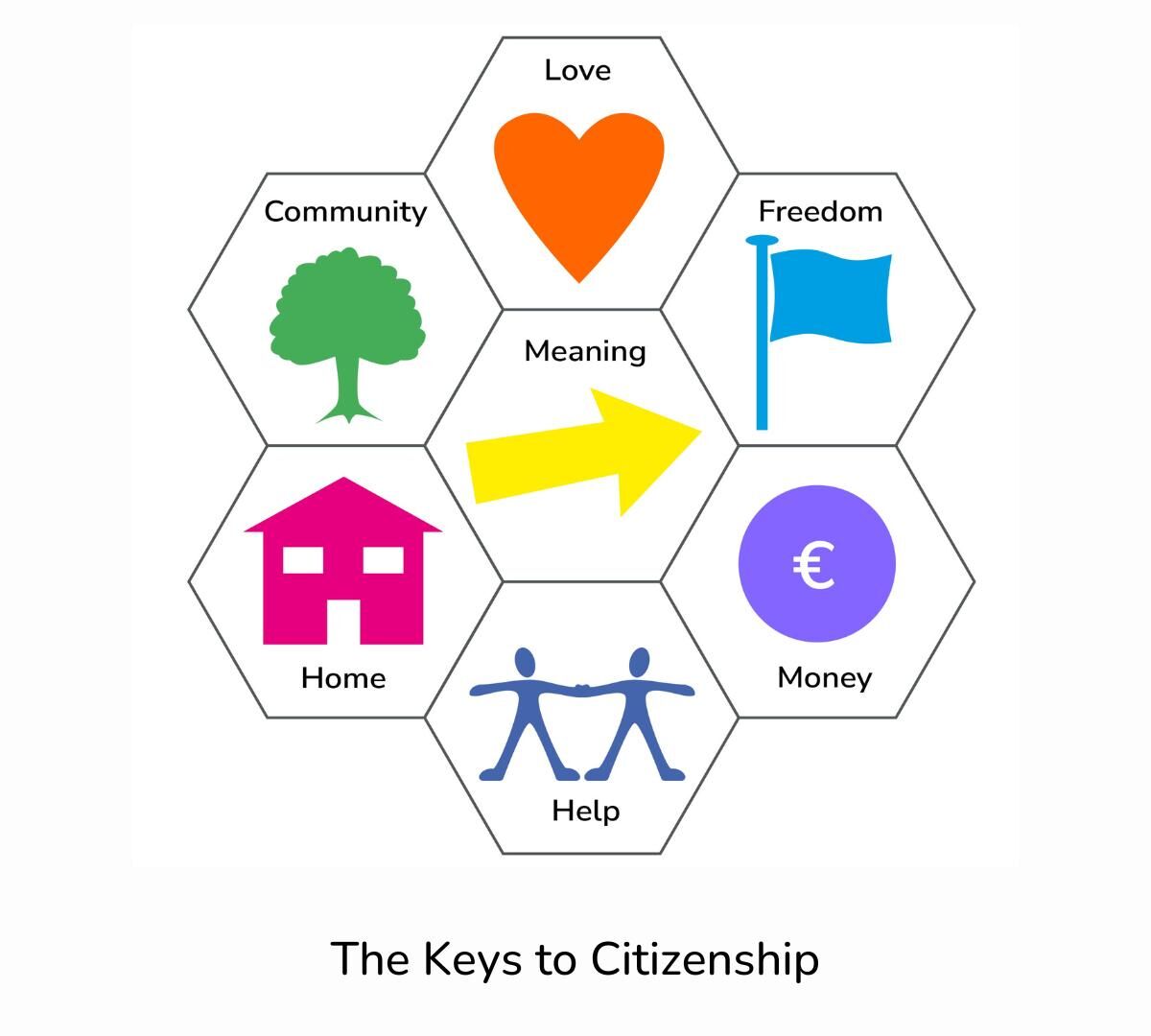

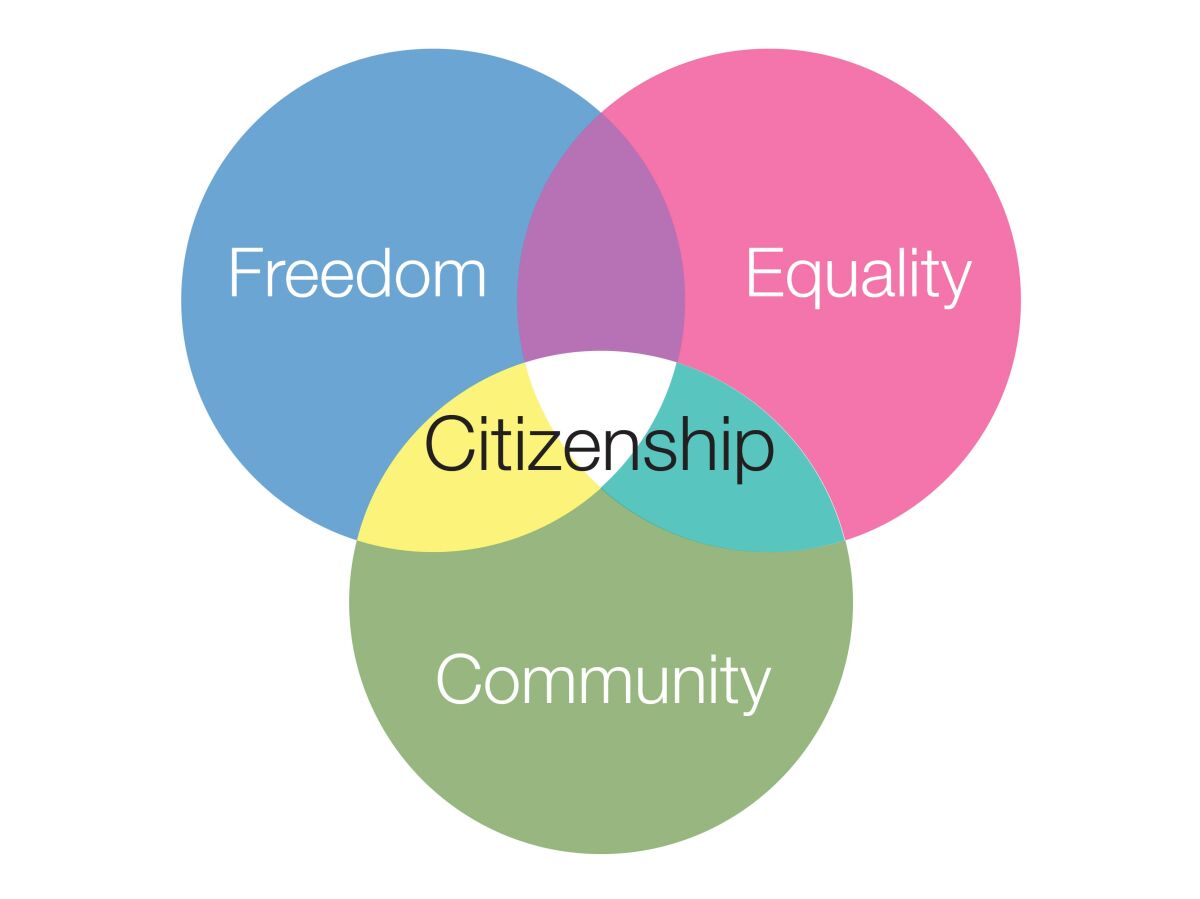

What Stephen’s story indicates that freedom is not just freedom. Freedom is an important dimension of our everyday citizenship. It helps us build a good life in partnership with those around us. After helping many people leave institutions I developed this idea as the seven keys to citizenship to share what seems like the most important dimensions of our citizenship.

1) Meaning - We all have our own gifts and dreams. We all have our own journey to make in life. We each need the chance to create our own unique life which is meaningful to ourselves. To live without meaning is not to live.

2) Freedom - We all need to be heard, to have our own voice, to take risks, make mistakes to have rights and to be able to make critical decisions about our life - in the small and the big things. Without freedom the human spirit dies.

3) Money - We all need enough money to survive with dignity, to be able to take the practical steps necessary to build a life for ourselves without relying on charity from others. Money is essential to our independence.

4) Help - But we all need help, to give help and to receive help. A good life is made up of a constant flow of assistance given and received. Without help we float like disconnected particles. A good life is lived together with others.

5) Home - We all need a home - not just a bed and a roof - but a real home. We need to be able to be safe and secure; we need to have our own things around us; we need to be able to invite others to visit or to live with others.

6) Community - We all need to share our gifts with the community. Community life can only flourish if it welcomes the gifts and contributions of all its members. The more people are excluded from community the more the community starts to die.

7) Love - We all need love. We all need friends, relationships, family and we all need to feel some love for ourselves. Love is the force for goodness, life and development.

So now we do understand something very important. We know that the purpose of our work is to help people build a life of citizenship. The test of our success is that if people are living as citizens.

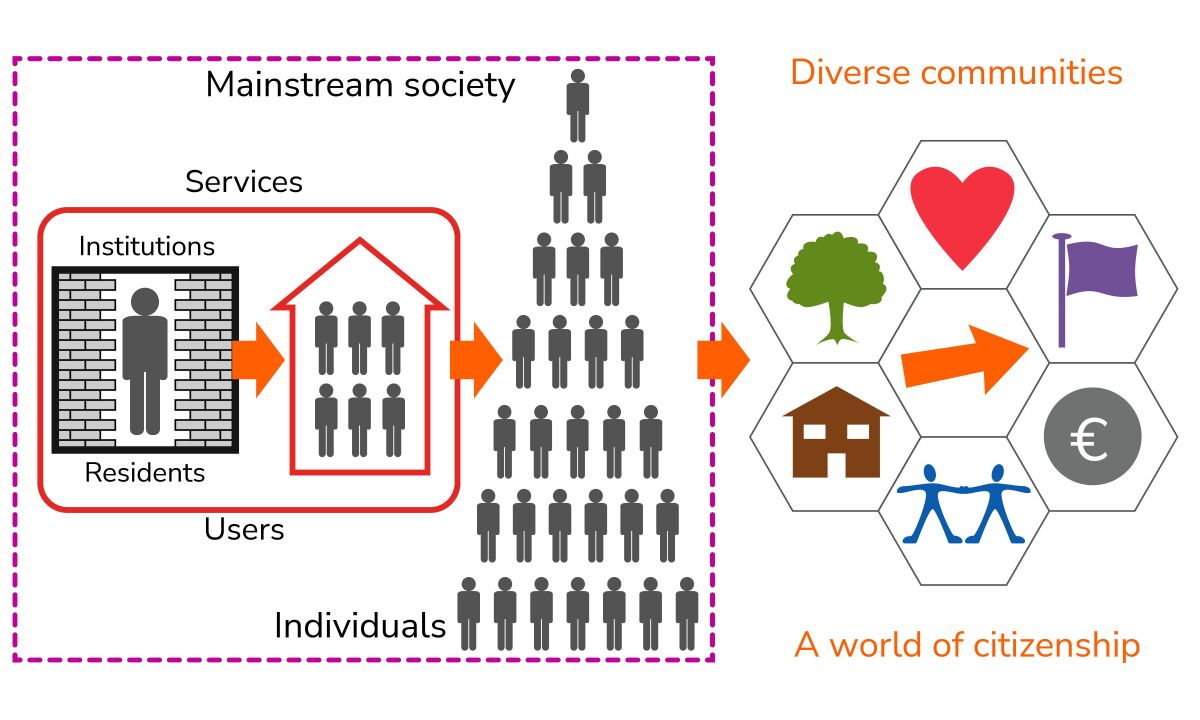

This is important because I think the history of deinstitutionalisation suggests that this is a hard lesson to learn. Often deinstitutionalisation programmes lead to the closure of large buildings, but people find themselves still living in a regime - in the community - but that is still controlled by other people. A regime of control can survive the closure of a building. Instead of a life of citizenship people get:

I think that the fundamental problem is that we are often still operating according to the broken values of the society that is generating institutionalisation, exclusion and social control. The purpose of life is our life not just to fit into mainstream society.

I think that what we are learning is that deinstitutionalisation demands we are willing to challenge the values of normal society:

This might not seem easy. It raises profound questions, not just about services, but how we all live together as fellow citizens. But while it is not easy, it is exciting and important.

This is the work you are doing. Bringing the true meaning of citizenship to life.

Another mistake we can make is to confuse the institution with the people who work in the institution. They are not the same thing.

Institutions do increase the risk of abuse, violence, sexual assault, theft and other crimes. But this is because a regime of control increases people’s vulnerability to abuse. But we must not exaggerate these risks or stigmatise staff who work in institutions.

To a very large degree the people who work in the institutions are good people, trying to do their best, in a system that makes it very difficult to do your best. However I have often observed that the people often get the blame, not the system.

This is very ironic because we should know that the problem with institutions is that they are powerful systems that mould and shape everyone who comes into their forcefield: children, families, adults, receivers of care, givers of care.

I have friends who led major deinstitutionalisation programmes in England from the 1980s and they often regret the way staff were treated and rather dehumanised in this process of deinstitutionalisation. If we believe everyone can live outside the institution then this means the staff too can overcome institutionalisation.

Here I would like to talk about something which, at least in the English-speaking world, it has become very difficult to talk about: professional boundaries.

This is a very difficult to topic to approach, because there are two genuine concerns. We worry that if staff become too involved with someone they may abuse their power or lose their objectivity. On the other hand we also worry that if staff are treated as friends people will lose the chance to build their own friendships and relationship. These are genuine problems.

But on the other hand, in my experience, good support or care is always a form of love. It is an attitude of love which opens our heart and minds to what people are really saying, what people really need and to a concern for the person’s true interests. And what people need to develop and grow is always love.

So I think we need to all think more about the meaning of love and relationships in our work.

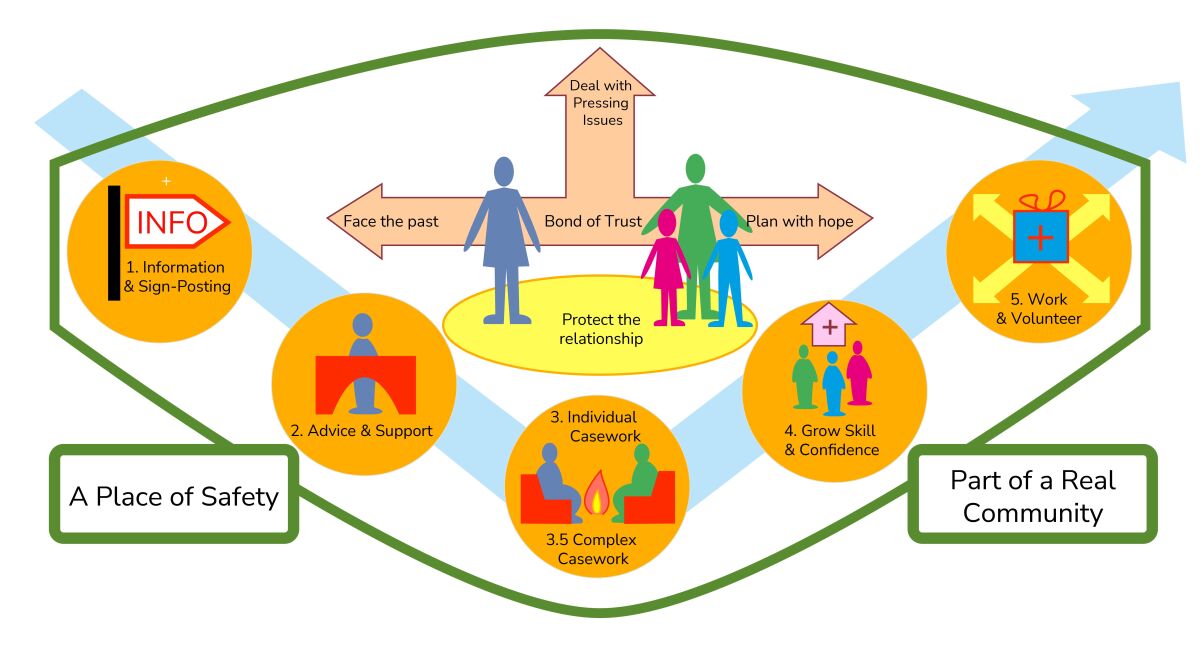

One of the biggest influences on my own thinking was learning about the work of WomenCentre with my friend Clare Hyde. Together we wrote a book about WomenCentre and its powerful work to support women and families.

They feel very strongly that the best way to support many women is by working as women, supporting women. In other words, putting gender at the heart of the work. Visiting WomenCentre and studying its very effective methods for supporting women - led me to understand more deeply that who provides us with support can be very important, in several ways.

WomenCentre is a service, led by women, which provides many forms of support to women across Halifax and Huddersfield - two towns in the North of England. But at the heart of their work was their work with the women and children who faced the most severe problems. These were women who could be seen as living in Hell - facing not just one problem, not just two problems, but multiple problems: victims of abuse, victims of violence, in trouble with the police, homeless, addicted to drugs or alcohol, suffering severe mental illness and physical illnesses. As a man who had spent most of my working life working with people with intellectual disabilities it was a shocking lesson in how other groups in society are also suffering prejudice and harm.

What was also shocking was that the public services could not cope with the complexity of people’s needs. The mental health service would pass women to the drug and alcohol service, who could pass women to social work, who would pass women to the homeless service. So on and so on. Many of these women were seen as too complex to be supported by funded public services. Instead only the WomenCentre would stand by these women and help them to solve all of these problems at the same time.

The model they used had evolved over several years and it combined a range of different options, but at its heart was a three-way relationship between women - women going through hell - women in paid work helping them with multiple problems - women who had been through hell and who shared their experience and gave hope to those suffering most.

Is this not a sophisticated and organised form of love?

In fact the staff at WomenCentre often saw their work as advanced mothering - giving women the powerful love of a mother - often women whose lives had deprived them of that powerful form of love.

So far I have argued that deinstitutionalisation must be a journey towards greater citizenship, for all of us. I’ve also suggested that we will need to recognise the force of love in this work, and being open to new forms of support and organisation.

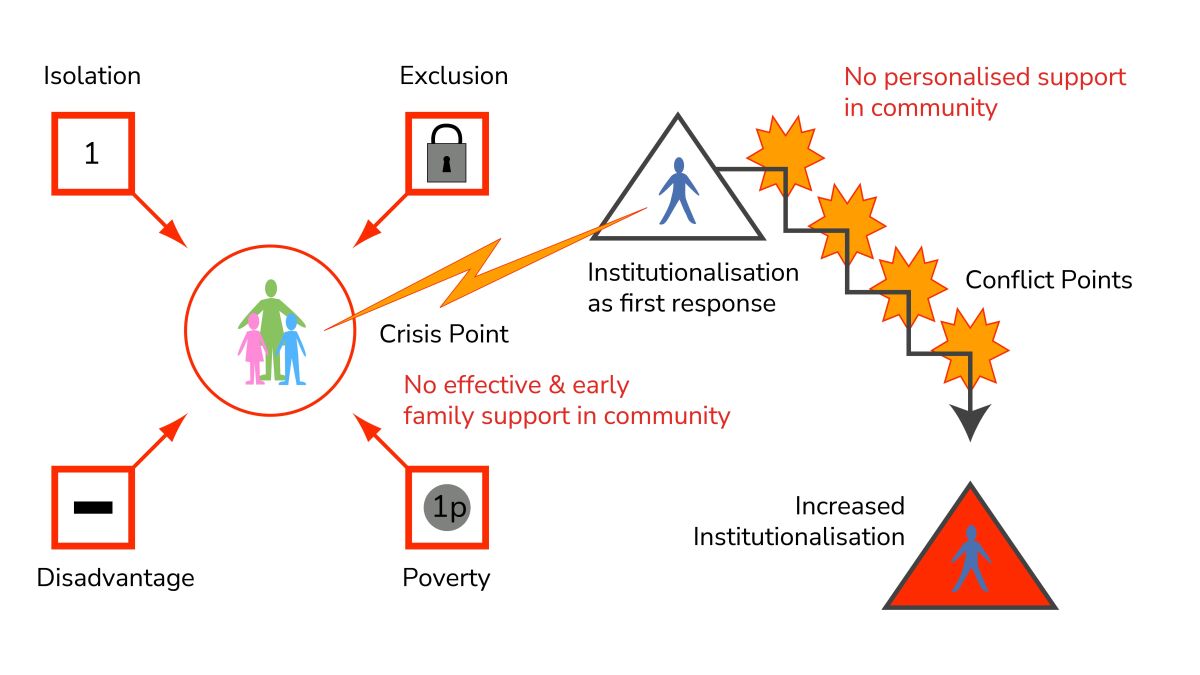

But now I’d like to think a little more about the forces that seem to keep institutionalisation in business. Back in 2011 there was a big scandal in England - the Winterbourne View scandal. A television company sneaked a film camera into a private hospital and revealed that the children and young people with autism and intellectual disabilities were being abused and humiliated by the staff.

Now in theory these places should not exist. England has supposedly closed all its institutions in 2010. But in fact, while the old institutions closed many smaller, private institutions were set up - specialising in people who were seen as more challenging. There are about 3,000 people, usually young people, in these institutions, and the number has not reduced despite many government announcements and strategies.

Shortly after the scandal I met many of the families whose children had been in Winterbourne View. Two things struck me: The families said Winterbourne View was the least bad institution that there children had been in. Think about that.

But also I found that every family’s story of how their child was institutionalised was almost identical. Each family had faced a crisis, an illness or problem which meant that they needed some extra help. But instead the only support their child was offered was a place in a group home. When the child got angry and upset at this change they were moved further away from their family into a more institutionalised services. And repeat. Until they ended up in institutions hundred of miles form their home - costing on average more than £170,000 per year (2012 prices).

Clearly, even though the big institutions are closed the system is still institutional. It generates institutional solutions.

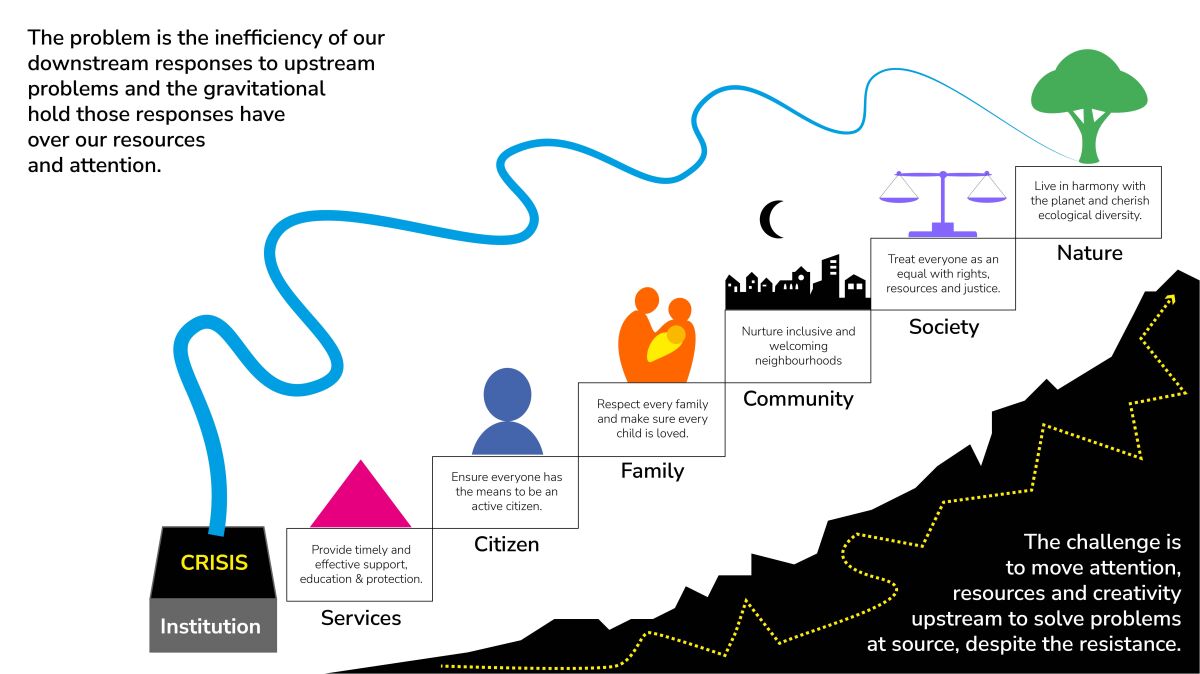

There are in fact many factors driving the kind of modern institutionalisation I’ve just described, but in this graphic I’ve tried to capture some of these factors and I’m suggesting that some factors are more upstream, more fundamental than others. In practice it is hard to change the factors that are further upstream, but we can tackle these factors if we apply good value, imagination and if we work together to learn what works.

1. The example from Winterbourne View points to obvious failures in the quality of support and service available. There was no personalised support to enable the person to stay with their family or find a community solution to their needs.

2. Beyond that there is a failure to recognise the rights and citizenship of all the people involved. Individuals and families were offered no control over their own destiny. The system took control over them.

3. There was no recognition of the rights and need of families. The needs of the family were ignored and they were not supported so that they could continue to support their child.

4. There was no effort to create community solutions. Instead money and energy was moved away from the community. Effectively wasting the communities resources on extractive solutions, weakening the community’s ability to solve solutions in the future.

5. That there is no recognition of the social injustice, inequality and lack of democratic accountability built into the system. For instance we would all be stronger we had a secure basic income to meet our basic needs.

6. Even further upstream is our divorce from nature. If we remember the history of the institution the basic reality upon which it was built was the fact that ordinary people were forced off the land, losing all the economic security the land gave them, and moved into a precarious existence, working for early capitalists and often working on resources taken from colonies and slave economies.

This may sound bleak - but there is so much we can do. This is our work.

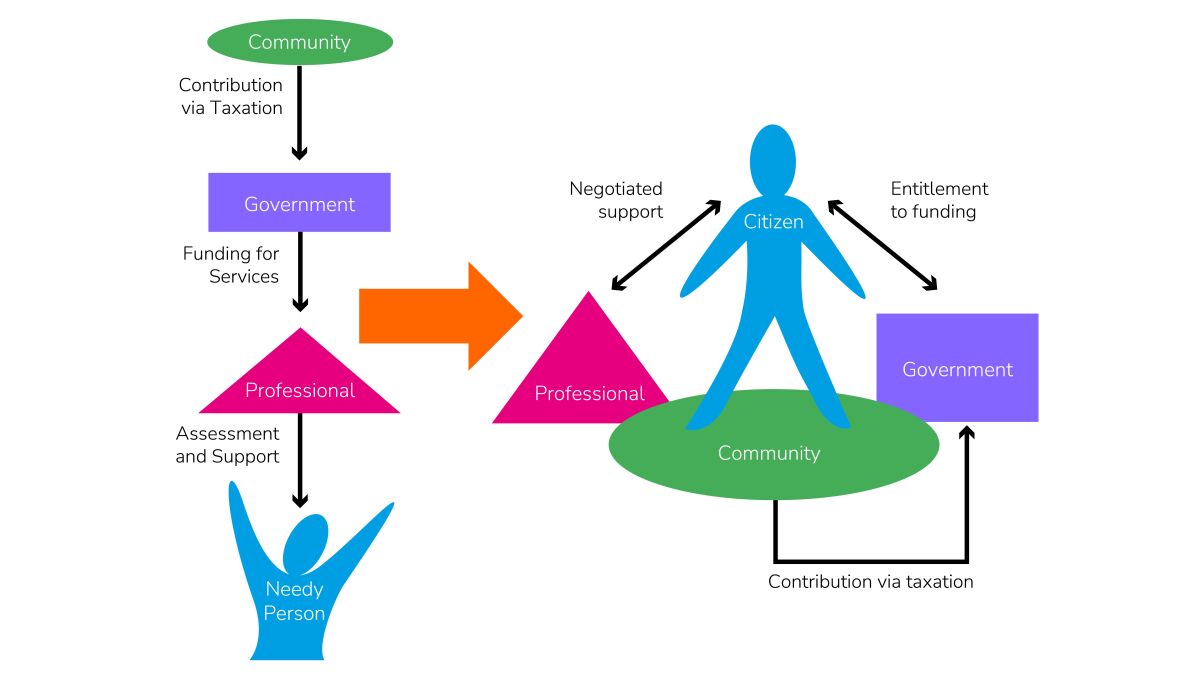

For example, for over 50 years more and more countries are rethinking how people can have control over their own support.

Instead of receiving services as a gift people can have entitlements that they can control.

Instead of services being fixed by decisions from above they can be reshaped in partnership with people and families.

Instead of treating community just as a tax payer we see community as the basic reality within which we build our lives.

Much of my own work has been focused on these efforts to reform funding and services across human services. In the last few years we formed the Self-Directed Support Network in order to help people in different countries learn and cooperate to increase the pace of change.

Stephen’s story was one example of this kind of approach, but there are many more and this approach works well in supporting families and children.

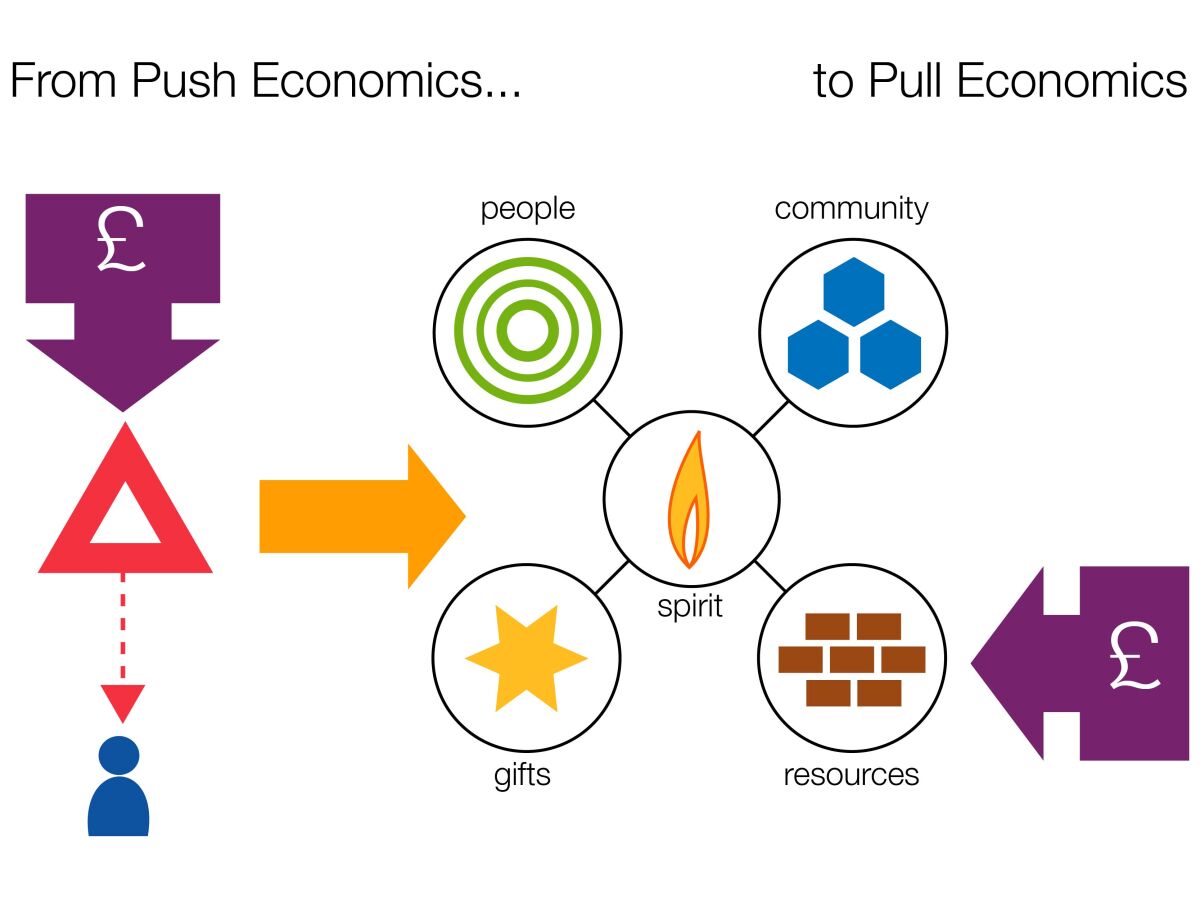

This approach to funding services is at its most powerful it is combined with a recognition that good things in life come through using our real wealth. Not just our money, but

Human beings are made to be resourceful, innovative and creative.

This mental model builds on the work of Dr Pippa Murray who described the real wealth of families in these terms.

But also the great advocate of inclusion, John O’Brien pointed out that we can distinguish two competing forms of economics here:

Push economics assumes that the system should spend money first, in the hope that it will have value. Pull economics assumes that people who have flexible control of money can craft much more efficient and effective solutions that build on their gifts and focus on their real needs.

There is overwhelming evidence of the effectiveness of self-directed support, including in work with children and families.

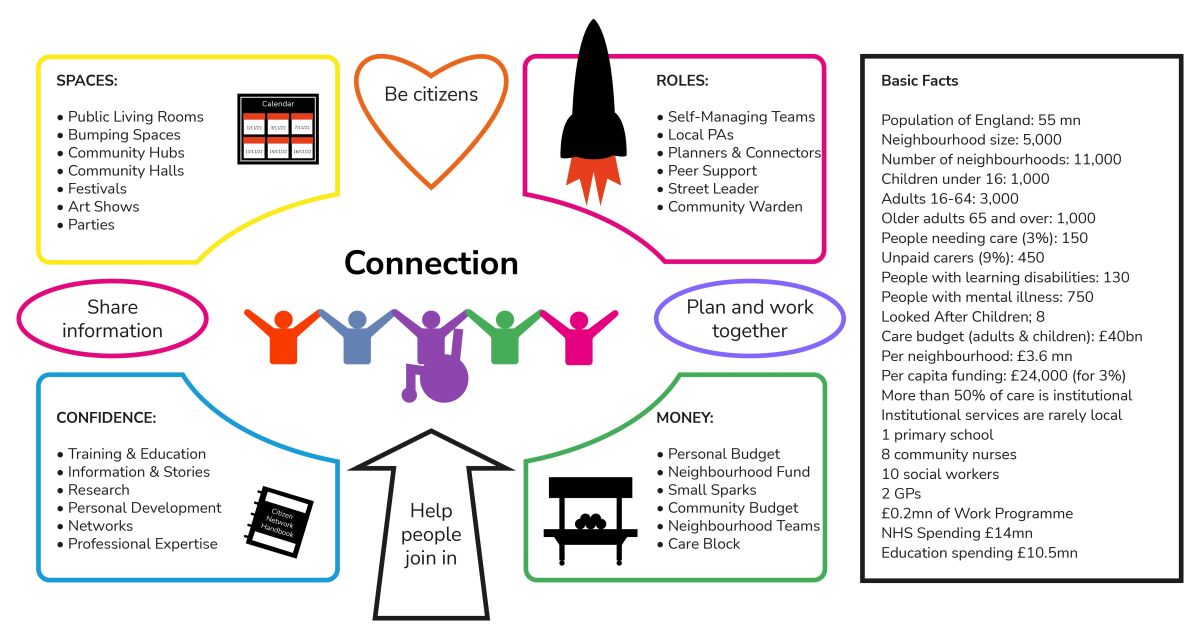

However today, the focus of my work is exploring the possibility that the next phase of innovation must be to explore what we can do to improve the small, human-sized communities that in English we call neighbourhoods or villages - which I think in Catalan might be called barris o pobles.

In fact I think that here in Barcelona you are leading much of this work with the development of Superblocks which reduce the strain on workers and increase the quality of care and community life by keeping people and resources locally. And I think there is so much that can be done by thinking differently about our neighbourhoods.

The framework in this slide is work in progress. I am talking to the communities close to me about how we can start to answer some of these questions. This isn’t just about one model or solution… its a new sustainable ecology for care. Taking a word from farming, it is about creating a regenerative approach that generates commitment, care and connections across the community.

I hope that this was not too much. I realise I have covered a lot of ground, very quickly.

I guess deconstruction can be messy.

But the fundamental thing, which it is clear that you already understand, is that the work is in front of us.

We can learn much from looking behind us, both the successes and the failures. But more important is a belief that we can find new solutions, better solutions, together.

We must keep our heads high and focused on the future we need.

A world where everyone is treated as an equal.

A world where every child will be surrounded with love and hope.

A world that understand that everybody matters.

Everybody has a contribution to make.

And it starts with us.

Today.

The publisher is Citizen Network. From Deinstitutionalisation Towards Neighbourhood Care © Simon Duffy 2025.

community, Keys to Citizenship, Neighbourhood Care, Neighbourhood Democracy, Self-Directed Support, social care, England, Spain, Article