Resource Allocation Systems (RAS) have become too complex. Barnsley and The Centre for Welfare Reform are exploring a radically simplified version of the RAS.

Author: Simon Duffy - with special thanks to Kathryn Smith and Barnsley Council

In order to give someone an Individual Budget there needs to be some kind of Resource Allocation System, that is some set of rules that helps people define a budget that is sufficient to meet their needs - before the person begins to plan. Unfortunately these systems are now becoming too complicated. The Centre for Welfare Reform and ibk Initiatives has begun to develop a new and radically simplified approach in partnership with Barnsley Council.

The first published RAS was developed by Simon Duffy in 2003, working with Wigan Council, and it filled one side of A4. This model was based upon on earlier work in Scotland where the RAS was based upon a professional judgement of sufficiency - what amount of money is enough to effectively meet a person's needs. However the RAS has continued to change since 2003; unfortunately it seems to have become increasingly:

Given the cost, confusion and difficulties of greater complexity it may be surprising that the RAS has become increasingly complicated; but there are at least 3 reasons why this has happened:

1. Failure of trust - setting a budget in advance means trusting both front-line professionals and citizens with information about what is reasonable. If we don't trust people then we will try to compensate by asking more questions and by reducing any reliance on judgement, experience and common-sense.

2. Centralised control - increasingly the RAS has been seen as a new mechanism for shaping and protecting spending in public bodies. As the ambitions about personalisation have grown so to has the desire to centralise decisions about the RAS - moving them away from the front-line and towards senior officers.

3. Phoney rationality - using questions, points, weighting systems and sampling methodologies lends an air of rationality to the internal mechanisms of the RAS. It is easy to feel that something so complicated must be more rational despite the fact that there has been no evidence that we need these more complex systems.

The appearance of rationality is often deceptive - more complex doesn't mean more reasonable. In particular it is very damaging to front-line workers and citizens to feel that important decisions about people's lives are now being made on the basis of obscure mathematical formulae that are decided 'up there'.

So we need some fresh thinking.

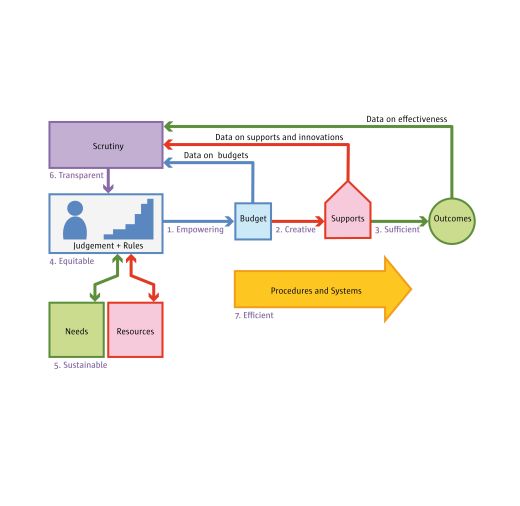

We could reduce the complexity of the RAS if we paid more attention to the purpose of the RAS. As the figure below suggests - it is not algorithms, formulae or 'rules' that determine whether a RAS is fair or reasonable - it is whether the RAS gives people enough money for support so that we can achieve the desired outcomes - in this case - to meet our needs.

What is more important than questions, points and weighting is whether the RAS focuses on:

Any system that helps answer those four questions will provide an adequate RAS; and ideally it should do so in a way that citizens and professionals can easily understand.

It is particularly important to remember that the 'indicative' quality of any Individual Budget means that the first guess provided by a citizen or a professional will still be tested by trying to develop a suitable service 'within' that budget. If it proves impossible to provide a suitable service within that budget this does not mean the RAS is wrong - it simply means that - in this case - the initial judgement must be amended. And this can be done by agreeing a new budget at a different level. It may be that the desire to 'get it right first time' has also driven the desire for a more complicated RAS - but instead it may be more sensible to allow for a degree of human judgement and common-sense instead of pushing for more complexity.

We have set out a possible new model below. This model avoids complexity and, it seems to us at least, has many other possible advantages over other prevalent RAS models. It still needs testing and further work. But it is published here - in its early form - because we believe too many places and too many people are struggling with unworkable systems - it's time to try something new.

This model was developed for disabled children - there would be differences for adults and for people with different needs - but these different systems would be easy to develop by working in partnership with citizens and front-line professionals.

Assessment - Budgets are set after the statutory assessment which is captured in a reasonably comprehensive and holistic report. The social worker (or other lead professional) then makes a judgement based upon their assessment of what would be a fair allocation for the family to reflect their circumstances and the needs of the disabled child. If an existing assessment is already mandated then it makes most sense to build on this and not demand additional assessments as part of determining the individual budget.

Entitlement - The lead professional clarifies what the family is entitled to receive - from Level A to Level L:

| Level | Individual Budget | Expected Number of People | Total Spend at that Level | Support |

| A | 0 | 50 | 0 | sign-post |

| B | 0 | 30 | 0 | sign-post and extra support |

| C | £500 | 30 | £15,000 | grant |

| D | £1,000 | 20 | £20,000 | grant |

| E | £1,500 | 20 | £30,000 | grant |

| F | £2,000 | 20 | £40,000 | = low level home care |

| G | £3,000 | 20 | £60,000 | = 1 night respite pm |

| H | £4,500 | 5 | £22,500 | = 1 night pm, plus care |

| I | £6,000 | 3 | £18,000 | = 2 nights |

| J | £8,000 | 3 | £24,000 | = 2 nights, plus care |

| K | £12,000 | 2 | £24,000 | = 4 nights |

| L | £15,000 | 1 | £15,000 | = 4 nights, plus care |

| Exceptional | £30,000 | 1 | £30,000 | complex package |

| Totals for Team | 205 People | £298,500 |

Planning - Families should then be able to use their budget flexibly to meet their needs. For grants the funding is agreed and payment made ASAP. For Individual Budgets families must provide a simple plan describing how they intend to use their budget - if this looks sensible then professional can get payment paid to an agreed schedule (the default would be monthly). All of this should be possible without the use of panels or undue bureaucratic delay.

NB - It also may be better to start giving clear renewal dates for all budgets, with short-term individual budgets being renewed more quickly than budgets where there is a long-term expectation of on-going need.

Ground rules - Families must know that they can safely plan up to the agreed level without having their plan picked over. Families must also know that if their plan is over-budget it will need further discussion and may not be agreed. There needs to be a strong incentive for co-production and the opportunity for families to get better value from the same level of budget. The system would not stop individual budgets being set at levels not specified in the table - and this would be for some agreed reason.

Disputes - Families must know that they are entitled to challenge their allocation and how to do so.

Expected Number of Users - The figure showing the expected rate of uptake of a certain level cannot be used to fix allocations. It is only used as a reminder of typical patterns of need and supports the professional team to manage their whole budget. It is useful because it allows for different approaches within different teams and it helps to keep responsibility for making sensible judgements at a team and professional level (not at a corporate or centralised level).

Equivalency - The Level of a budget must be sufficient to purchase a suitable service that is sufficient to meet the needs of the disabled child and family in the view of the social worker. It cannot be right to set a budget at a level unless you have good reason to believe that this level is reasonable and that someone could get their needs met with that budget. Clarifying an equivalency in this way is not meant to discourage innovation - quite the opposite - but it does help avoid legal challenge, because it shows that the budget does reflect some real model of how a need might be met.

The opportunity for the family is to meet those needs in a way that is even better for them as a family that the system would have done. Moreover, as new standards for good support are set by self-directing families then these levels and their equivalences will need to be reviewed and changed. These levels are not fixed, they are snapshots based on the state of knowledge about how best to meet needs at a point in time.

Legality - although UK law on the right to support is weaker than it should be it is still vitally important that we build on all the guarantees it provides - for children and for adults. This approach may make it easier to clarify how an eligible need is being defined and what level of resource is being treated as appropriate to meet that need. More complex approaches to the RAS seem in danger of inserting new - but legally unfounded - principles into the allocation of the budget.

This model has not been tested yet and it has been designed with a specific team in mind. It still needs testing and is NOT a local policy. It is published on the principle that it is better to share good ideas so that they can be improved. Please feel free to adapt this model and to try it locally. Please let The Centre know if you have any success or find you can make any useful changes.

Published by The Centre for Welfare Reform.

Simplify the RAS © Simon Duffy 2011.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

education, local government, Resource Allocation Systems, Article