Hanne-Maria Leppäranta demonstrates the powerful impact of personalisation on the practical day-to-day work of a social worker.

Author: Hanne-Maria Leppäranta

It all started with a horse.

Before I started working as a social worker, I was a full-time caregiver for a disabled family member, my son, for four years. During that time, I became proficient in modifying our services to better suit our needs.

For example, my child was not eligible for personal assistant. Our local welfare office for the disabled would have judged him unable to direct an assistant because he is too young, unable to speak and has a developmental disability. But he wanted to ride, and needed help with changing bus lines and following teacher’s directions during the riding lesson. I’m very allergic to horses, so I was unable to assist him. I solved the problem by choosing to use my caregiver’s vacation days (3 days in a month) for three vouchers with value of 100 euros each. The vouchers were valid for several service providers which offered personal assistance services for 2-3, 5 hours for one voucher. I hired an assistant for my son through a service provider, and he took riding lessons for three years. Technically, I was having a vacation every time my son had a riding lesson. One can - and should - ask whether is it reasonable to use up vacation days to make up for not fitting in service criteria. But the path to change interpretation of law is through court, and life often requires a faster solution. Enter the service personalization.

During my social work studies, I worked in several different fields, including a psychiatric hospital. Social work in a hospital setting in Finland usually means that you get to have a good, confidential relationship with your client, but you have to get very creative to produce results. Both features are based on same two facts. A social worker in a hospital can’t make decisions, and she doesn’t have a budget for acquiring services. Commonly the work consists of helping the client to fill applications for Kela, Finnish Social Insurance Institution. But there are cases which require more, and I feel that a social worker should be able to offer something better in difficult situations than simply referring the client to webpages he can find on his own. To help a client, one has to look outside the traditional field of available services. For example, if the sickness allowance is already used up but the client feels he is unable to work, is job alternation leave an option? Job alternation leave is an arrangement where a worker gets allowance for giving up his job for an agreed length of time and the employer hires an unemployed youth as a replacement. The worker gets time off and a financial compensation for wage loss from employment services, and the youth gets working experience and a salary. The end result is much the same. The client does not work, and gets money to live on, but the name of service is different.

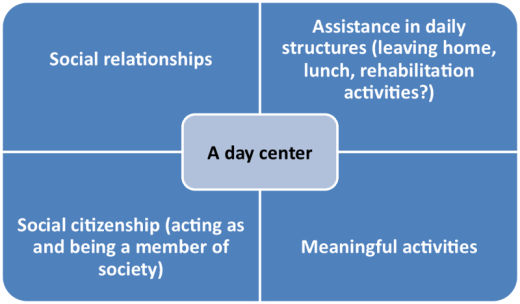

The same approach works on most services. Take a day center, for example. When a social worker recommends a day center for a client, what are we actually recommending?

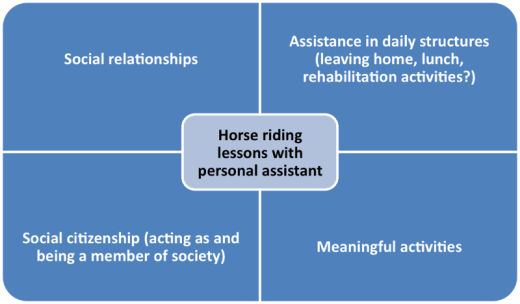

If these are the values which make up the service “Day Center”, I could achieve the same goal by switching the service like this:

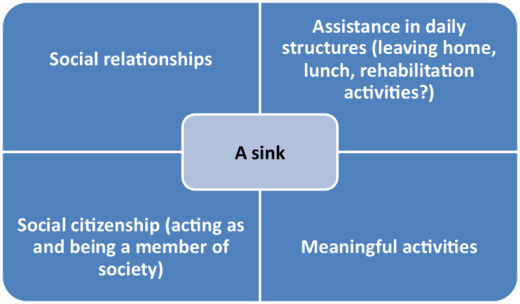

Or, if we take the idea a bit further?

Yes. It’s a sink.

I enjoy working with autism spectrum clients, and one of my clients was a young man moving out from assisted housing unit to his own apartment. After the move was over, my assignation was to help him to move forwards with his rehabilitation and find a path back to working life. First step is usually finding a work try-out placement. He, however, told me that he was unable to think about work try-out because he was having serious anxiety due to a problem with one of his special interests. I believe that when working with the people on autism spectrum, any issues concerning their special interests should not be underestimated, but taken at face value. I inquired about the issue, and he told me that he collected feathers. He had several thousand feathers in his apartment sauna, but not enough space to wash, dry and organize them for storage. The local bird watching society didn’t have enough room, either.

If a client is not in condition for a work try-out placement, the alternative option is usually a day center. My client did not want to go to a day center. He told me that he didn’t want to make handicrafts and chit-chat with other people. He did fine with social interactions as long as they concerned actual, practical issues but he found purely social occasions very unpleasant.

I had an offer from local day center. To buy their service for my client, it would cost 135 euros for a day. And he didn’t want it. What he actually wanted was a place to arrange the feather collection. I asked him what kind of place it should be, and he told me there should be a sink and lots of table space. So I spoke my supervisor, who arranged me a chance to visit executive board meeting. I prepared figures, and made a short presentation on how we could assist the client and save money by personalizing my client’s services. Essentially, I asked if I could please have a room with a sink instead of a day center service.

I got the sink, and a trial budget for a year for personalising services for clients in need. I rented a classroom from local school during the winter holiday, and my client put his feather collection in order. The issue was solved, and we were able to move forwards. While I’m writing this, he is working in a work try-out placement which is a very good fit for him professionally, and excellent result for social services’ point of view. I compared the cost of his previous services (living in assisted housing unit which offered help also during evenings and weekends) to personalised services. The costs of assisted housing were 56 000 € for a year. We spent 17 394, 45 € on his personalised services in twelve months. The trial was successful and the next year’s budget included money for personalising services.

Naturally, it depends much on your superiors and whether they are open to new things. I have been very lucky in that regard, but I believe that there are few things which help. The recipe is

Courage + Preparation + Story

Courage. It is not easy to go there and ask for something unconventional when the person you are trying to win over is a complete stranger four or five steps higher in the workplace hierarchy. Also, even if you get permission from your managers, trying to arrange personalized services for your client can be a very interesting experience in society where tools like personal budgets are not yet available. People might not necessarily believe that you are a real person or working where you claim. Prepare for that. It does get easier with time after you have built up a reputation as the person who gets all ‘odd’ assignments. Having that reputation is a mixed blessing, and it might not be what you want. I’ve found mine rather amusing, but I have a sarcastic bent. I had a social work intern who sighed and said that his internship of nine weeks had destroyed his paradigm of social work entirely. He had learned the traditional route from appraisal to offering a service, and the common principles of working with the clients. In university, he had been taught to maintain eye contact and ask open questions, but my autism spectrum clients found eye contact uncomfortable and open questions diffuse.

Preparation is essential. Social workers tend to lose arguments when their reasoning relies solely on values which are hard to measure. If your main argument is ‘quality of life’, or ‘what is best for the client’, you need tangible details to support your claim. Otherwise your argument is just an opinion, based on your own professional or personal judgement, and it might not carry a lot of weight. Without proper argumentation to back you up, the outcome depends more on your personality and standing than the client’s needs, and that is never an ideal situation.

A real life example. There was a client who went to a day center, but the client, his family and the social workers felt that he did not get enough assistance in the day center and needed a personal assistant. Usually, a day center staff is responsible for providing assistance, but in the client’s case, it was not enough. We had to find a way to prove the need, and show how the client’s situation was different compared to others in the day center. After discussing the situation with the client and his family, I spent two days in the day center, just sitting there and writing down how his day progressed and how often he needed help. I took minutes on how long he had to wait for assistance, if he got assistance, and how long it took. Based on my notes, I wrote a report and compared the combined minutes to number of workers and clients in the day center. From the data, it was obvious that the client needed more help than other clients in the day center, and the other clients were not getting enough assistance because the staff resource was tied up to one client. With the data, we were able to argue the need for personal assistant successfully.

(For people using this technique, I recommend taking more than one surveillance day. The presence of an observer makes everyone try their best, and even though it is nice, it does not give realistic picture of situation. In this particular case, there was significant difference in my numbers between day one and day two. Three days might have been even better, but it was not possible with my workload at the time).

So you have courage, and the numbers to back you up. The third ingredient in my recipe is a good story.

A story does not mean you should come up with a fairytale or colored tale of your client. Stick to the truth. But borrowing the idea of elevator speech from the corporate world is not a bad thing. You should know your client well enough to be able to tell your managers what does he want? Why he wants it? How it would help him? Your superiors do not have time to go through the client’s history from last ten years, but they will usually give you five minutes.

The background preparations you have done give numbers, but they don’t give the incentive. Generally, people are inclined to do good things when they are given an opportunity and a reason to do so. This includes your superiors. As a social worker, it is your job to pass your client’s story to them, and provide the reason. It might sound commercial, but break it down like we broke down the idea of service in first chapter. When you speak on your client’s behalf, trying to promote a solution he wants and needs, you are, in fact, advocating for social justice.

“It’s not going to work because our town is much smaller.”

Whenever I give a lecture about personalising social services, the people coming from small municipalities claim that personalising services only works in a bigger city because there are more options available. I disagree.

When it comes to personalised service, there are no ready-made options. That is the meaning of ‘personal’.

When people turn to personalised services, their needs are highly individual. I don’t think there is a service provider who conveniently offers feather arranging rooms, anime card roleplaying groups for people with speech disability, or a rehabilitation program for resisting orange stickers. In health care field, the possibilities are more limited because the nature of needs is different and the system works via qualifying professionals on what they are allowed to do. There is a bit more leeway in social services. Personalised social services are created by finding someone, describing the issue, and asking if they can help.

I had a client who had problem with buying groceries. He could use money, and unpack his items into refrigerator at home. He was very thrifty, and wanted to save money. From social worker viewpoint, a good characteristic. But he was on the autism spectrum, and got stuck on items marked with orange sale stickers. They were nearing the expiration date, and therefore price was lowered by -30% or -50%. He bought everything which had a sticker, and was unable to appraise if it was possible to eat them before they became inedible.

In a small town with one or two grocery shops, it would be very simple to ask permission from client and then have a talk with shop staff. “If you see John coming with a cart full of discount sticker items, could you ask nicely if he is going to eat them all in two days?” A polite reminder might eventually do the trick.

But in larger city it’s not working so well because there is no community. It’s a bit too much to ask a dozen shops and their every cashier to remember who John is. Making it work with larger group of people would likely require his picture placed as a memory aid on the checkout point, which is not acceptable in terms of his privacy. We ended up hiring a neuropsychiatric coach to help him work on the issue, but working with a shop would have been better option. For shop, it would be a good customer service and a regular customer, not too much extra work. For client, a bit of help he needs, and more time to practice the skill than we could offer through a coach. It could be a permanent arrangement, until he no longer needs it.

One of my clients had made a similar arrangement on his own. He is an active athlete, who uses a wheelchair and trains at a local gym twice a day. The gym is essentially his day center service. Because he can’t get into gym through the front door, he calls the staff in advance and they help him inside using the freight elevator at the back door.

Having a smaller community might be actually helpful for developing a personalised service. Finding a roleplaying group focused on anime card games from a small community might be out of reach, but you could look for one online, especially if speech disability does not include problems with writing. Or integrate the service by making the roleplaying group a community college course available for all interested people in the region. Then it could benefit a larger group of people, and offer the added benefit of integration for the client. Most things are possible, if you just ask, and asking is always easier when you already know who is in charge of community college course planning.

“My case load is too heavy to think of personalization.”

Two social workers with the same number of clients might have very different caseloads. If the social services are able to fulfill the need for support, the contact with a client might be as little as updating the service plan once a year. But a demanding case might take up as much time as three or four easier cases. I’ve found that those hard cases are often clients who feel their needs are not met.

Personalisation can be used to lessen the workload. Clients who are satisfied with their situation are generally very easy to work with. It is true that personalization requires more time, and a different approach in the beginning. But it is a tool to build trust between social worker and a client. Unhappy clients look for help from several different places and people. They also are less satisfied with social worker’s decisions, and file more complaints. Communication between social worker and the client might require more time and effort.

Building a good relationship with a client does not necessarily mean you have to come up with a complicated, strongly personalised plan for his services. I usually apply for a personalized service when I feel I know the client well, and I have a good grasp on his situation. Personalisation comes into picture when I know why the mainstream services don’t work for the client, and what he wants.

You can start with little things. I had a file where I had written down each client’s preferred way of communicating. Whether they wanted e-mail or text messages, phone calls, letters or meetings. I didn’t send letters to a client who said his letters always got lost in the mail. We used secure e-mail instead. If I knew my client had problems with understanding, or memory, I sent him a text message because he could show it to others and ask for help, or read it as many times as necessary. It is a small bit of personalisation which is possible regardless of one’s field or position, but it made my job easier because I could trust the client had gotten my information. It’s no use to send letters if the client says he doesn’t like opening his mail.

Start with something small. Test it. Ask people what they want. You might need to ask several times. Think creatively, and don’t stop at the last entry on your local service provider list. How would you do this, if you were trying to solve the same problem in your personal life, and not as a social worker? If your client was your friend, or a family member? Look at the third sector, and communities, and use your common sense. If your 19-year-old client wants something to do, creating a schedule from a free, local clubs and groups meant for young people might work just as well - or better - than a day center or a specialised service.

Have courage, and joy in your work.

The publisher is the Centre for Welfare Reform.

Practical Social Work is Personalised © Hanne-Maria Leppäranta 2017.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.