The UK's housing market is over-inflated and even progressive policies like basic income cannot solve this without other reforms.

Author: Malcolm Henry

Over the last decade interest in the concept of universal basic income (UBI) has been slowly gathering pace. Since the Covid-19 lockdown and its consequential interruption to the incomes of most households interest in UBI has transformed into widespread advocacy.

The logic of UBI in comparison with the hotch-potch of salary and business support schemes that are being implemented in the UK and elsewhere is inescapable. Most people need money right now to pay the bills and the UBI is the most effective and efficient way of ensuring that no-one is left wanting.

UBI enthusiasts can see the prospect of their dream coming true as our economies – so utterly reliant on wage-earning – struggle to come to terms with lockdown. But a hasty introduction of UBI without fully understanding its effects on some essential components of our economy could undermine its effectiveness and provide its opponents with ammunition.

UBI will significantly increase the disposable income of the population as a whole, providing the productive economy with lots of opportunities for new business. However, not all of these opportunities will be beneficial to us, individually or collectively.

Some of the things that we spend our money on are essential to life, and the markets for some of these essentials are effective monopolies because of the infrastructure that’s required to deliver them – electricity, gas, water, etc. Even with regulation the people who control these markets are adept at inflating prices whenever there is an opportunity to do so, and UBI is a golden opportunity.

At first glance housing might appear to lie beyond the reach of such avaricious monopoly but we have to look beyond the bricks and mortar to see who controls prices in the housing market.

Land Registry and ONS data show us:

These rates of increase represent a gargantuan amount of money. Where has it come from?

To put £1,499 billion into perspective, the UK money supply (M4) at the end of 2019 was approximately £2,500 billion, which means that around 60% of the value of all of the money in the UK economy is owed in residential mortgage repayments.

Given the UK population’s addiction to the property market it is highly probable that a significant proportion of the additional disposable income from UBI will exacerbate the existing problem of house price inflation.

A proportion of the population in receipt of UBI will use the extra disposable income to invest in residential property – moving to a bigger/better home; buying a holiday home; investing in buy-to-let. Such investments will inevitably be geared – the spare UBI cash being multiplied threefold or more by mortgage providers.

The supply of residential property is limited by the number of people who want to move house and the number of new houses that are being built. Any increase in demand will certainly lead to an increase in asking prices.

Banks will happily respond by issuing mortgages that cover the inflated prices, encouraging more people with disposable UBI income to enter the market and contribute to further house price inflation. The more that banks lend – value and quantity – the more income they get from fees and interest.

The net result will be higher housing costs for everyone who rents or who has to move house due to a growing family or relocation.

But there will also be a negative effect on the rest of the economy. Money that could be used to support productive activity will be sucked into the coffers of mortgage providers and landlords and largely lost from general circulation.

For an economy to thrive money must be available and mobile. UBI is probably the best method of ensuring that a base load of money passes through every corner of the economy every month but its effectiveness will be severely compromised if a significant quantity of it is diverted into housing costs.

The continuous inflation of housing costs will also exert pressure to continuously increase the value of UBI payments which will create difficulties in the UBI funding mechanism.

If UBI is to work as its proponents imagine then there is a range of essential goods that will have to be protected from inadvertent or opportunistic price inflation. Housing is a prime candidate for such protection.

Controlling the price of housing is, technically, relatively straightforward given that the primary driver of inflation is the provision of mortgages.

Every residential property on the market must have an up-to-date home report prepared by a chartered surveyor. The report includes a Valuation which is the surveyor’s best guess at the market value of the property. It also includes an Estimated Reinstatement Cost for Insurance Purposes. This is how much the building would cost to replace (like-for-like) if it was destroyed. The market values of residential properties are inflated directly by mortgage providers responding to and encouraging demand. The insurance values are inflated indirectly because builders can charge more for their work when mortgage providers are pumping up the market value of the finished article.

Introducing legislation that restricts lending by a financial institution for the purchase of residential property to a percentage of its insurance value will, in most sectors of the market, eliminate mortgage-driven house price inflation and curtail inflation driven by the building industry.

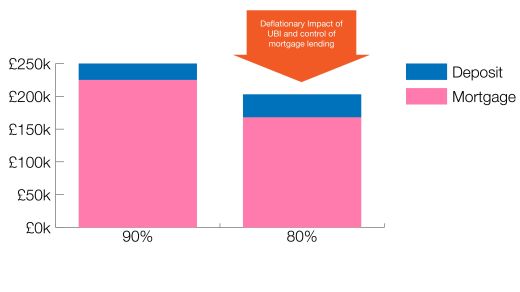

The market value of a house that I want to buy is £250,000.

The insurance value is £210,000.

Currently I can get a mortgage for 90% of £250,000= £225,000.

I have £25,000 saved for the deposit so I can pay the market value of £250,000.

Mortgage lending is restricted to 80% of the insurance value = £168,000.

I have saved my UBI for a few months so can add a further £10,000 to my initial £25,000.

The maximum I can pay for the house is £168,000 + £35,000 = £203,000.

Transition from the current inflationary system to a non-inflationary one will require some adjustments to be made in the contracts between mortgage providers and their existing customers.

For each property the difference between the market value when the mortgage was issued and the current insurance value will have to be calculated. Where this figure is positive the principal of the mortgage will be reduced accordingly.

The customer will only be liable to pay the balance of the principal up to the current insurance value, and only the interest on that portion of the principal.

The provider will be permitted to write off the liability for the portion of the principal above the current insurance value. The Treasury will compensate the provider for the interest on the written-off portion of the principal.

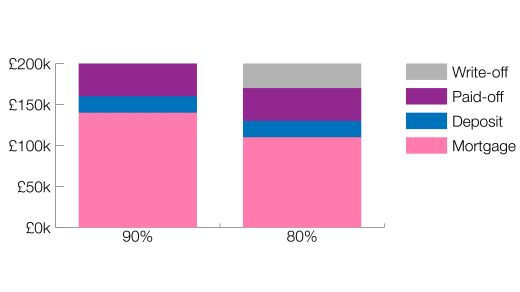

The market value of your house when you bought it was £200,000.

You paid a deposit of £20,000 and took out a mortgage for £180,000.

Since then you have paid off £40,000 of the principal of the mortgage, leaving £140,000 outstanding.

The current insurance value of your house is £170,000.

Our new legislation reduces the mortgageable value of your house by £30,000 (i.e. £200,000 minus £170,000).

Your provider writes off £30,000 from the principal of your mortgage leaving you with £110,000 still to pay.

You pay interest only on the remaining £110,000.

The Treasury pays interest to the mortgage provider on the £30,000 that has been written off.

Both customer and provider will see a nominal reduction in their capital worth but the reduction will be universal across the housing market so there will be no relative loss when someone is selling to buy a new home.

The mortgage customer will benefit from reduced repayments and earlier outright ownership of the property.

The mortgage provider will benefit from guaranteed interest payments from the Treasury for the portion of the principal that has been written off, eliminating risk of default.

If the proposed legislation includes provisions to restrict residential rents to a percentage of the insurance value of the property the transformation from a system that encourages inflationary bubbles to one that is UBI-friendly will be complete.

Mortgage-driven house price inflation is already a problem in many of our communities, excluding those on lower-incomes from the housing market and artificially pushing up rents.

The debt repayment burden on these inflated mortgages, and the consequential inflated rents, are a drag on the productive economy, removing money from circulation that could otherwise be helping our communities to thrive.

The introduction of UBI will be an opportunity to address these problems by implementing a solution like the one outlined above, protecting the integrity of UBI and releasing the productive economy from the burden of excessive housing costs.

The publisher is the Centre for Welfare Reform.

Popping the Housing Bubble © Malcolm Henry 2020.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

Basic Income, housing, tax and benefits, England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Article