Individual service design is the creative development of high quality supports to achieve full and active citizenship.

Individual service design is the creative development of high quality supports to achieve full and active citizenship, using the full range of possible resources.

Early champions of Individual Service Design include people like Beth Mount and others who began to challenge standardised services for people with learning difficulties. Instead they began to use person-centred planning to generate supported living solutions - ways of supporting people that enabled them to live a full life and which didn't try to make fit within fixed service models. In the UK Peter Kinsella led the movement for individualised support for people with learning difficulties in the 1990s. Later on organisations like inclusion Glasgow and Partners for Inclusion and others put Individual Service Design at the heart of organisational design. This led to the further development of Personalised Support.

The proper function of Individual Service Design is to support people’s citizenship. Good service design is the creative process by which we organise support that suits our life. Creativity arises from the tension between the positive aspirations of the person and those around them and real-life constraints. By challenging, adapting to or transforming these constraints it is possible to create decent, personalised support and enable active citizenship.

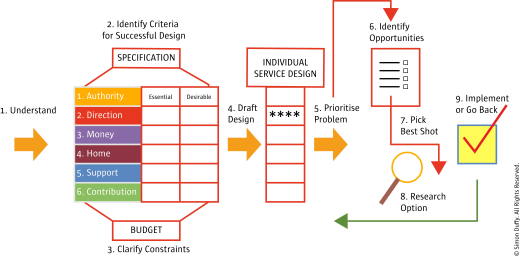

The process is often complex, iterative and will rarely follow a standardised path. However the following steps demonstrate some of the key challenges of Individual Service Design:

A good service design is built on a good understanding of 4 very different things:

Creativity is stimulated by an understanding of the criteria of success, the precise goal. In fact (using rather unattractive language) we might say that a good design is going to be tested by how well it achieves the individual service specification. The specification identifies what is either essential or desirable for a successful design.

Once you have a coherent account of what would be right then you must review their circumstances in order to define the initial constraints within which you will be working. Constraints are not bad, they are natural and inevitable. Where we find a constraint we must try and make that constraint work for us by asking “So if that is fixed how do we still achieve our goal?” Necessity really is the mother of invention.

But it is also vital that we do not imagine constraints that are not there or imagine that the fact that we don’t know how to do something is a constraint. Our own ignorance should not be treated as a constraint and we will only stop being ignorant if we learn to do something we’ve not done before.

The service specification defines the problem you are trying to solve within the given constraints. The service design is your attempt to solve that problem. The ideal service design will therefore:

If you can draft a service design which meets both of those criteria then you are doing well. Your only major challenge is to then implement that plan. However, in practice, it is not always the case that you know how to meet all the specification; in which case it becomes necessary to identify both the likely shape of the design and the unresolved issues that require further work.

Using your draft service design you now need to work out which issue to tackle first. There is no one component that should always be treated first. Possible criteria include:

It is far more important to decide to focus on one thing than it is to focus on the right thing, or worry how to define the right thing. If you focus on the wrong thing then you will find out. At that point you will just need to go back and try another tack.

In order to generate options it is important to both clarify constraints and to explore possible opportunities. To make this process as effective as possible you may find it useful to both generate a shared list of known constraints and unexplored opportunities. The richer your understanding and the broader the group who are generating these lists the more effective the exercise.

The process of brain-storming - coming up with lots of ideas quickly without worrying about which are the best ideas - is almost always an effective means of exploring a large number of possible opportunities. Notice however that this requires discipline; it is easy to get lost in evaluating the one idea without first generating your list of options.

The next step is to review the possible opportunities in order to identify those that are worth further research. As at step 4 it is not necessary to make the right decision here; for if you make a mistake you can simply come right back and try another approach.

Possible criteria for selecting the most likely opportunity include:

Sometimes the service design may throw up genuine conflicts or contradictions. If this happens it is possible to help the individual to recognise this and seek some compromise by helping the individual think about what is most important to them. It can be useful to spell out contradictory options, list positive and negatives for the person and then let them choose.

Unless you are lucky enough to have all the key decision-makers in the room then exploring your most likely opportunity will probably involve going and talking to somebody else or finding out information from somebody else. This should not be seen as a disadvantage. In fact it is the very need to go out and talk to others, especially others who do not come from the service world, that indicates you are attempting to do something both creative and good. If the solution lay immediately at hand then it could be the kind of easy but impoverished solution that services readily arrive at.

The key is to work out how best to research the possible opportunity to stimulate the response you want. Research may not be the right word, for it suggests that what you want to do is rather passive or academic. Instead your role may be more like that of a good salesperson, a networker or a persuader.

Be sure that you know who it is that you need to persuade and make sure that you have a good case. Ideally you want all the key decision-makers on board with you. Ideally you are trying to give somebody a problem that they are ready-made to solve. Bankers like to lend money. Lawyers like to write contracts. Public authority’s like to believe they are saving money. Play to their strengths and offer them problems that they will find satisfaction from solving.

Each plan or decision you come to will involve work, research or further actions. Creativity arises out of the combination of thought and action and you need patience and commitment to be creative.

Once you have brought together the principles of the service design and the resources that appear as constraints or opportunities then you must decide the best way forward:

Clearly this process of making decisions about service design is complex. For each individual the order in which problems are solved can change and there is little likelihood that you can resolve these matters in one go. But in reality this process is not actually difficult to go through and any errors tend to be self-correcting.

This process is also much closer to the ordinary process of making big life decisions that we all go through. We do not sit in a room, look at some information about ourselves, and then decide how everything in our lives needs to be organised. We do it bit by bit, focusing on the things that seem to make the most sense to solve first.

The publisher is The Centre for Welfare Reform.

Individual Service Design © Simon Duffy 2010.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

Person-Centred Planning, Personalised Support, Inspiration