This analysis was carried out on behalf of We Are Spartacus and estimates how the end of DLA will hit local government.

Author: Simon Duffy of the Centre for Welfare Reform, on behalf of We Are Spartacus

The replacement of DLA with PIP will damage local communities by reducing the incomes of people in poverty, reducing charging income for social care and increasing the numbers entitled to social care. An average area will lose £7.5 million, but could add further costs of up to £11.25 million.

The government intends to reduce spending on Disability Living Allowance (DLA) by replacing it with Personal Independence Payments (PIP) [1]. This changes will be phased in by 2018, by which time it will cut the incomes of disabled people by £1.5 billion [2]. This means that an average local authority, with a population of 300,000, will lose income that has been targeted at disabled adults of over £7.5 million. This will be a further blow to local economies. In addition it will inevitably have a further knock-on effect for the social care system.

A typical local area will find that 2,250 people will lose income that was helping them to manage the extra costs of their disability. This will have two affects:

It is common practice for local authority means-testing of disabled people to take into account benefits. So, as many of those who will lose DLA are currently entitled to social care, those people will currently be subsidising social care through their DLA income. This income will now be lost to the social care system.

DLA also helps disabled people to pay for the extra costs of travel, support and daily living and helps them to stay independent. Over 50% of disabled people currently live in poverty and DLA represents a vital element of a person’s income. When 2,250 people lose that vital income then many will become newly entitled to social care. This is because their income for support has been reduced and so it will become more difficult for them to meet their basic needs and they will thereby become eligible for social care through Fair Access to Care Services (FACS) - the regulations that define entitlements for social care.

It is important to note that PIP has been designed to reduce the incomes of disabled people (the fiscal target was set before any ‘reforms’ were designed). There is no evidence that it was previously over-claimed or claimed fraudulently. People on DLA are people with significant disabilities. Their loss of income is bound to increase the level of unmet need within the community and will therefore increase the pressure on social care.

It is also important to note that FACS is focused on the degree of risk to independence for someone within their current environment. Ideally it is sensitive to risk and mindful of context. PIP is focused on functional competence with regard to a set of activities. So there is no reason to believe that many people who have lost their eligibility for DLA will not thereby become eligible for social care.

This would mean that the saving would have disappeared but the costs would have simply moved from central to local government.

Of course the real context for local government is even worse. Local government will be cut by over 40% by 2015. Social care will be cut by 33% by 2015 [3]. These new cost pressures from the loss of DLA will simply speed up the breakdown of the social care system. Local government can only respond by increasing the level of means-testing in social care, raising eligibility or squeezing the level of personal budgets to unsustainable levels. This breakdown in the social care system will then put further pressure on more expensive systems - NHS, education and even prisons.

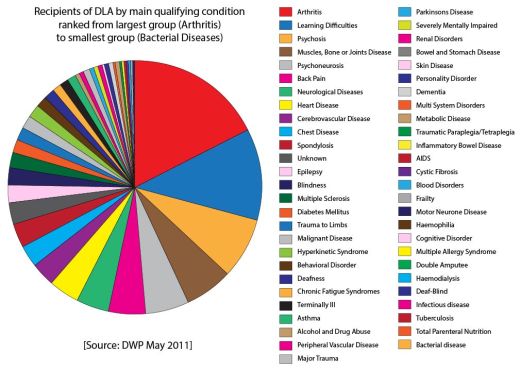

It is also important to remember that Disability Living Allowance is an important source of support for about 3 million people with significant disabilities. It has never been easily available and the conditions which lead to an entitlement include serious health problems and impairments. The following data slide represents the current pattern of entitlement.[4]

The table below describes the conditions of those currently entitled:

| Arthritis | 562390 |

| Learning Difficulties | 380250 |

| Psychosis | 245030 |

| Muscles, Bone or Joints Disease | 197440 |

| Psychoneurosis | 177940 |

| Back Pain | 150960 |

| Neurological Diseases | 150960 |

| Heart Disease | 125070 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 102920 |

| Chest Disease | 91250 |

| Spondylosis | 91060 |

| Unknown | 88520 |

| Epilepsy | 72350 |

| Blindness | 69630 |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 63680 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 58790 |

| Trauma to Limbs | 53300 |

| Malignant Disease | 51540 |

| Hyperkinetic Syndrome | 51510 |

| Behavioral Disorder | 45900 |

| Deafness | 42950 |

| Chronic Fatigue Syndromes | 38190 |

| Terminally Ill | 34890 |

| Asthma | 31780 |

| Alcohol and Drug Abuse | 21340 |

| Peripheral vascular Disease | 20850 |

| Major Trauma | 20220 |

| Parkinsons Disease | 18310 |

| Severely Mentally Impaired | 17080 |

| Renal Disorders | 16640 |

| Bowel and Stomach Disease | 15900 |

| Skin Disease | 15880 |

| Personality Disorder | 15180 |

| Dementia | 14850 |

| Multi System Disorders | 10840 |

| Metabolic Disease | 10270 |

| Traumatic Paraplegia/Tetraplegia | 9380 |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | 8740 |

| AIDS | 8000 |

| Cystic Fibrosis | 7160 |

| Blood Disorders | 5610 |

| Frailty | 1990 |

| Motor Neurone Disease | 1820 |

| Haemophilia | 1600 |

| Cognitive Disorder | 1390 |

| Multiple Allergy Syndrome | 1170 |

| Double Amputee | 1100 |

| Haemodialysis | 580 |

| Deaf-Blind | 570 |

| Infectious disease | 450 |

| Tuberculosis | 330 |

| Total Parenteral Nutrition | 320 |

| Bacterial disease | 70 |

| TOTAL | 3202900 |

| DWP Date 2011 | |

| Source: Guardian Data Blog |

[1] Kennedy S (2012) Personal Independence Payment: an introduction. London, House of Commons Library.

[2] DWP (2012) Personal Independence Payment - Reassessment and Impacts. London, DWP

[3] Duffy S (2013) A Fair Society? how the cuts target disabled people. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

[4] DWP (2011) Disability Living Allowance: how it breaks down. The Guardian Data Blog.

The publisher is The Centre for Welfare Reform.

Impact of PIP on Social Care © Simon Duffy 2013.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

Cumulative Impact, social care, tax and benefits, England, Article