How individual service funds (ISFs) can lead to new ways of supporting people in their own communities.

Author: Chris Watson

This article was first published by the Institute of Public Care (IPC).

There has been an explosion over the past few years in new types of locally based care, support and training delivered by personal assistants (both employed and self-employed), micro enterprises and umbrella organisations (who often act as matching and coordination agents for a fee).

These innovations have been driven by community spirit, entrepreneurialism, individual creativity and a desire to do things differently. To date they have mainly been reliant upon the flexibilities of self-funding or direct payment arrangements and are still relatively small scale in comparison to other more developed elements of the market providing only limited capacity.

This article explores how these new models of care could be grown by local commissioners to meet additional demand using individual service funds.

The already overstretched independent social care workforce, which was running at an estimated 110,000 vacancies (Skills for Care, 2019), is in many areas now under unprecedent pressure to maintain services continuity whilst also providing flexible, responsive and person centred support to a range of vulnerable adults living in communities.

In order to meet current and future demand for care and support the government has recently initiated its national Care for Others. Make a Difference recruitment campaign which aims to support care providers with filling their existing vacancies and with the overall effort to ensure the sector wide impact of Covid -19 is kept to a minimum.

Whilst this campaign is welcome (and many in the sector would say long overdue) some of the past structural issues with recruitment and retention have also centred around the sectors generally low pay rates (driven by the previous need to continuously reduce council’s overall expenditure year on year thereby holding down the hourly rate of care) and societies wider label that care work is a form of ‘unskilled' labour.

The recruitment campaign may well raise public awareness of the essential and complimentary nature of care in relation to the NHS but it does not solve the wider issue of the hourly rates paid to providers in some areas and subsequent low pay offer.

Presently, in most areas of England, health or social care direct payments are still the only vehicle available to people wishing to enjoy the additional flexibility and control of their support that is offered by employing personal assistants.

According to Skills for Care’s report on Individual employers and the personal assistant workforce (2020) there are now 70,00 direct payment users who directly employ their own staff resulting in an estimated PA workforce of around 135,000 people.

Alongside this workforce data the report also highlighted that PA’s:

Yet despite the obvious benefits to direct payment holders, in terms of stability of workforce and longer staff retention levels, according to the latest Adult Social Care Activity and Finance Report, England 2018-19 the uptake of direct payments remains low overall relative to commissioned services.

Figure 1. Number of clients accessing long term support at the end of the year, by support setting and age group, 2018-19

Some of the factors behind this may include:

Many of these issues are effectively embedded in systems, policies and practice and will require time and ongoing effort to fully resolve – making the rapid expansion of the personal assistant workforce less viable in some areas at present.

Recently the CQC has been working via the Regulators’ Pioneer Fund on a ‘sandbox’ project to explore the development of regulatory standards for personal assistants, micro enterprises and umbrella organisations (or bodies).

In particular its focus is upon ‘if and how’ to regulate umbrella organisations that:

These organisations have been developing organically in a number of areas around the country and have been creating a new type of self-employed workforce that is rooted in local community connections and that are based upon long term relationships between the person and their supporters. They also tend to use self-managed teams’ principles and methods and have a strong interest in community networking, and asset and strengths-based approaches to support.

It is the authors understanding that the sandbox work undertaken to date has been positive and is likely to yield a formal status for these organisations that will involve the adoption of a set of inspection standards becoming a validated part of the regulatory framework.

This shift from micro enterprises being seen as creative, but essentially fringe operators, to becoming accredited, mainstreamed and regulated bodies has already significantly improved the routes available for people to choose how they are supported.

At present there are an ever increasing number of micro enterprises offering a wide range of types of support to people living independently in the community via direct payments (Small Good Stuff is a national directory accessible here), services include:

Expanding the umbrella body model by pro-actively approaching local individuals and organisations to become sole traders or to become micro enterprises would provide additional capacity for new referrals coming into the system but also a swathe of the current population that had previously been averse to using direct payments for reasons outlined previously.

From a financial perspective Skills for Care’s research (2017) indicates that personal assistants enjoy a slightly higher rate of pay than the independent care sector average and those coordinated underneath micro enterprises can potentially achieve a higher rate again. For example, an umbrella organisation in Somerset charges the direct payment holder £17.10ph with £13.68ph going directly to the worker, which before tax and NI equates to an annual salary of £26,265 pro rata.

It is important to note, for fairness, that this doesn’t include some of the benefits of being an employee, such as annual leave or a pensions contribution, and in some areas where local authorities are already paying higher overall hourly rates to traditional domiciliary care providers the pay differential may be significantly less.

What is also interesting about this model from a commissioning perspective is that overall hourly costs can be broadly comparable with homecare agencies (potentially even less) but with more of the total hourly rate going directly to the worker. Micro enterprises and umbrella bodies tend to be smaller and have far lower operating and management overhead costs than bigger organisations, the neighbourhood basis of care delivery significantly reduces travel between customers and associated expenses too.

The neighbourhood basis of micro enterprises means that people are matched with workers who are geographically close to them, (generally within a handful of miles) this reduces commuting time and associated costs and may make it a more attractive option for people who want to work part time offering smaller slivers of their time around other commitments.

It is also likely that in most cases a higher percentage of the money spent on personal assistants and micro enterprises will be retained in the local economy. In larger organisations there is often a flow of money out to other areas for overhead costs such as head offices and centralised back office functions situated in other areas of the country. The micro enterprise approach fits well with the principles of the Keep It Local campaign of which several local authorities are now signatories.

It is not envisaged by the author that micro enterprises will take the place all of the other types of care and support that are currently being delivered - it is likely there will always be a place for a wide range of different organisational forms to maximise service availability and individual choice and control.

It is possible that these approaches can be used to augment existing arrangements and increase the range of creative support that is available. There is potential though, that in some harder to supply areas the neighbourhood basis of micro enterprises may offer the possibility of better continuity of support.

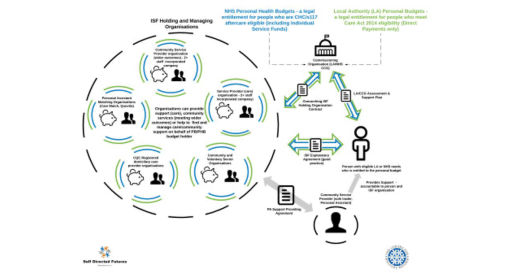

Individual Service Funds (ISFs) are a model of commissioning that allows people to engage with a wide range of different types of provider organisation in order to flexibly meet their assessed outcomes. To date around England ISFs have been used mainly in more traditional forms of delivery such as domiciliary care organisations and day centres.

ISFs offer an opportunity to present almost the same levels of choice and control to the recipient but without the bureaucracy often associated with a direct payment or with becoming an employer. Effectively this contracting model opens up the possibility of commissioners, working directly with a range of micro enterprises and umbrella bodies, in particular existing voluntary and community sector organisations, to expand the numbers of locally based personal assistants that are available to provide community based support and, in future post CQC approval, also regulated personal care.

The diagram below shows how this can work contractually:

Figure 2. ISF commissioning and contracting arrangements

For Citizens

For Communities

For Commissioning Organisations

References:

Skills for Care (2020) Individual employers and the personal assistant workforce. Skills for Care

Skills for Care (2019) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England. Skills for Care

The publisher is the Centre for Welfare Reform.

Growing New Models of Support © Chris Watson 2020.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.