Cormac Russell argues that welfare reform in isolation of the enlargement of the commons is naive and counterproductive.

Author: Cormac Russell

Cormac Russell is one of the leading champions of citizen and community as the solution for many of our social problems. Here he explores the relationship between the welfare state and community. He argues that neoliberalism is further undermining our commitment to community and that it is only by attending to the conditions of our active citizenship that we will properly redefine the role of the welfare state.

1. The Welfare State is an important extension of our human community’s capacity to care; not a replacement for it. Communities produce care (full-stop) and the systems or service world should simply be the support to that care where required, a resource to carers and not the source of care.

2. These ideals have become confused in the last 150 years by different social service models, to the point where community care has become systematically outsourced, commodified, monetised and accordingly displaced from its rightful place of origin: the commons, and dislocated into institutional space. This has undermined citizenship, democracy and our commonwealth, and created the construct that John McKnight aptly calls the 'Careless Society’.

3. The view that our welfare is determined by our community assets, not institutional programmes, underpins the ethic of deep democracy and is the only viable antidote to Neoliberalism. It’s a view that is confirmed by the great preponderance of epidemiological evidence (not ideology) regarding our primary drivers towards wellbeing, which include our individual agency, our associational life and our economic and environmental circumstances. It is a view that brazenly defies the attempts of the marketplace to keep us dissatisfied, so that we consume more.

4. While it is critical that we urgently find a new expression of the Welfare State, one that is an extension of us, not a replacement for us. We must grow that expression from inside communities, out. Welfare reform in isolation of the enlargement of the commons is naive and counterproductive. The enlargement of the commons is a necessary prelude to a new expression of the Welfare State, not a by-product of it.

5. Our institutional systems have reached the limits of what they can do to secure our welfare. Actively getting behind personal budgets and Basic Income, we (as citizens not employees of organisations) can reclaim the ground from where 'welfare' is produced: our commonwealth. This must be our primary focus, the 'builder’s stone' on which the supportive functions of the state can be redefined and refunctioned.

6. The above five points do not preclude a functioning Welfare State where healthcare services, social care and social protections are properly funded. Instead it defends them by standing shoulder to shoulder with them, recognising that there are three domains from whence welfare is produced:

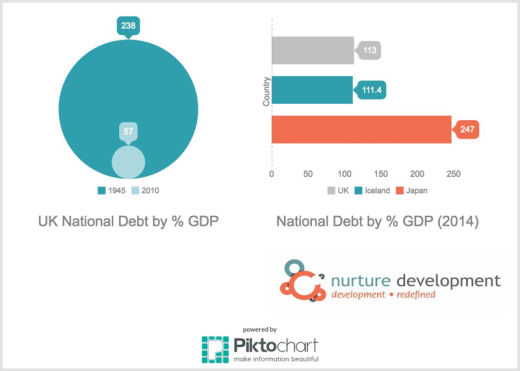

According to Barry Kushner and Saville Kushner(1) when the welfare state as we understand it today was introduced in the UK at the end of the second world war, the national debt peaked at 238% of GDP. Still, as well as introducing the welfare state, the National Health Service and council housing were also introduced.

In stark contrast, recent austerity measures were introduced at a time when national debt was running at 57% of GDP (2010), lower than Italy, France, Germany, Japan, and the U.S.(2) The debt was not the actual or actuarial reason for austerity; neoliberal hegemony was, and continues to be. Hence nothing that has been stated above should be misconstrued as an apology for cuts, rather it argues for a renaissance of the welfare state which can mount a credible corroding argument to neoliberalism, true to the original spirit and ideals of its founding architects.

David Boyle’s engaging piece in the Guardian Professional (2014) aptly captures those ideals:

“When William Beveridge released his famous blueprint for the welfare state at the end of 1942, his assumptions suggested that the cost burden would reduce over time because welfare spending would progressively reduce need.

As we now know, he was wrong. It wasn’t just him; the same mistake was made in most welfare states. The problem wasn’t that Beveridge failed to slay his ‘five giants’ – ignorance, want, squalor, disease and idleness – but that they came back to life in every generation, and had to be slain all over again. Every time at increasing expense.”

In an attempt to offer an explanation for the current malaise Boyle goes on to say, rightly in my view:

“The difficulty was that Beveridge’s welfare services developed in a direction he never intended: over-professionalised; dismissive and suspicious of the neighbourhood networks which had underpinned people’s lives for generations; undermining informal advice and support; allowing the ties of mutual support to atrophy.

Services developed the attitude that high-tech equipment, sophisticated processes and professional knowledge is somehow all that is required to provide help to the grateful, passive multitude. Two generations later, those informal networks of support have been corroded.”

Today, it's the corrosion of those informal networks, alongside hyper-individualisation, consumerism and austerity that have combined to form a perfect storm. A storm that will further devastate low income communities and those who are most marginalised from society and the economy.

I have previously argued that we have alternatives to the demeaning welfare arrangement we currently provide. Ironically to find exemplars for such alternatives, we must again return to the end of the Second World War and this time closely examine the structure and ethos of The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, known informally as the G.I. Bill. Here we see what happens when governments treat people like heroes, not spongers. The former enables people to be of value in their economies and communities and the latter misrepresents people as untrustworthy drains on the systems and the tax payer’s money. There was a time when ex-service men and women were putting down payments on houses, had resources to start up their own businesses and return to education on their own terms. Those times are long gone. They were replaced with services, and more recently even those services are being cut.

A significant amount of the money spent attempting to help people with professionally diagnosed ‘needs’ and ‘problems’ has prevented those people from sharing their gifts and living a life of their choosing. Hence denying them of their most basic needs/rights for belonging, autonomy, competence and security, and therefoer creating far greater and more impenetrable problems than they originally presented with. Is this not neoliberalism wearing the mask of love?

Ethical helping professions, instead of asking people ‘what is the matter with them?’ ask, ‘what matters to them?’ The former reveals the need for programmes, the latter reveals a yearning for life, and a huge reservoir of sleeping gifts.

Powerful citizens accept no less from those who serve them, and their neighbours. They also understand that if they do not do what is best done in civic space then it will not get done. Hence the functioning Welfare State at best is an extension of us; not a replacement for us.

Cormac Russell is Managing Director of Nurture Development and a faculty member of the Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) Institute at Northwestern University, Chicago.

References:

1. Barry Kushner, Saville Kushner, Who Needs the Cuts? (London: Hesperus Press, 2010, Pg.39)

2. Ibid.

The publisher is the Centre for Welfare Reform.

The Welfare State is an extension of us, not a replacement for us © Cormac Russell 2016.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

local government, politics, social justice, Article