Simon Duffy outlines an alternative path for achieving meaningful integration between heath and social care.

Author: Simon Duffy

Much of the talk about health and social care integration is confused and its supposed benefits are dubious. We forget why the systems were developed differently in the first place and we forget the different roles they play in people’s lives.

Ultimately all public services are reunited at the door of No. 10. After this it is the job of Government to intelligently divide things into some logical, if always slightly arbitrary arrangement. We can’t have a Ministry of Everything responsible for the integrated delivery of all public services.

There are of course important points of contact between different public services. But it is not clear that new forms of integrated governance make things better, for with each new piece of infrastructure come new complexities. For example, health and social care integration is now central to social policy in Scotland; but in practice this appears to have only led to further complex structural change, involving the creation of new statutory bodies, linked back to both local government and to the NHS. According to some leaders in Scotland integration is actually very damaging, undermining work to advance disability rights and focusing on a narrow health agenda.

Not that integration in England makes any more sense. Lansley’s NHS reforms led to radical disorganisation and confusion across the NHS. Recent talk of integration in England seems to mean no more than an effort to cross-subsidise social care, using NHS funding, as local authorities are devastated by severe centrally imposed cuts. These kinds of non-reform are not new; they have been introduced and reintroduced over the last few decades. They are merely forms of structural and financial re-engineering; they will never lead to any long-term meaningful change.

Health and social care integration is often promoted as the key to greater efficiency, but when it is conceived in terms of shifting money or organisational boundaries, it becomes just another meaningless reorganisation.

Moreover, if we look forward to the challenges of the twenty-first century, we can see that these organisational forms of integration are irrelevant to the real opportunities and challenges of the future. The critical challenge is for public services to work differently with communities and with citizens. It is this capacity, which lies latent within our communities, that is the key to innovation and improved public services, not the technical or structural changes that are internal to public services (Duffy, 2013). It is the interface between people and the welfare state that we should focus on, not the interface between different public services.

Barnsley is one place where there is a real chance of shifting the focus of integration on to the right questions. Barnsley have worked hard at system integration, but they have also been pioneering in other areas too. For instance, Barnsley were early champions of personalisation and the use of self-directed support in social care. Today most of the adult social care budget is now controlled by individual citizens - designing their own support in ways that make more sense to them. However this change has also started to influence many other elements of how Barnsley think and works.

In particular Barnsley has focused on:

All three of these strategies are important, however in this short article I am just going to focus on the first strategy - enabling citizen control.

Barnsley is made up of over 230,000 citizens - children, women and men - people of different faiths, and none, different ethnicities and different backgrounds, interests and personalities. Together they are the citizens of Barnsley.

It is natural that public services will often focus on the needs of citizens. But there is a significant risk that a needs-only focus will encourage us to treat individuals as passive objects, requiring only assistance from the state. Citizens do not just have needs, they also have rights, desires and their own projects. Instead of treating needs and wants as two separate things it’s important to see that in a fair society needs should be met in ways that are consistent with self-development and well being.

In other words, if you simply meet my needs then you will tend to define my needs for me, and in the light of the resources that are available to you. But if you enable me to define and meet my own needs then I will be able to create new solutions that are more consistent with my own identity, development and resources. Maslow’s well-known hierarchy of need can be adapted to make this clearer:

Figure 1. Two different approaches to Maslow's hierarchy of need

Understanding this distinction is critical to take forward innovations like self-directed support. If a citizen’s entitlement is treated as if it were merely a new mechanism for existing public services meet the needs of the individual then it will become just another unnecessary complication in our public service system. There will be no room for citizens to shape their entitlements to meet their own needs in their own way. Instead, understood properly, the budget should be treated as an entitlement that the citizen can control to get the support they really need.

It is this model that also helps explain why citizen control can be a powerful mechanism for improving the efficiency of public services. When citizens control resources and direct support then they are better able to build on their own real wealth (Murray, 2010). Our real wealth is made up of the following:

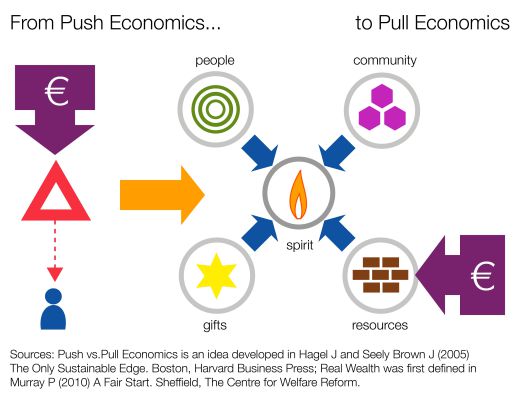

When people have control of resources they can integrate them with their real wealth in order to create better outcomes, with greater efficiency. This is a shift from push economics to pull economics: instead of public services spending money on things that they hope will be important to people they enable people to spend money on what is actually important to them.

Figure 2. Why self-directed support is efficient

Unfortunately self-directed support is often confused with consumerism. Despite the available evidence, many policy-makers continue to incorrectly believe that the improved efficiency of self-directed support has to do with ‘markets’ and consumer choice. This is inaccurate. In order to make the best use of self-directed support it is necessary to avoid some of the mistakes that undermine its effectiveness:

Barnsley MBC has had significant success in using personal budgets in social care. At the end 2014 77% of adult service users had some kind of personal budget, that is 1,897 people out of 2,464. Within this there are 400 direct payments and 6 Individual Service Funds (ISFs). In addition there were 80 direct payments for children, and 20 for continuing healthcare packages (CHC).

Barnsley MBC also runs a support service for people to develop their own support packages, with assistance for people to plan and organise support. There is also a local system for recruiting, training and employing personal assistants as well as an online service for people who wish to buy their support online.

This means nearly all of the Long Term Care funding for Barnsley (9% of all health & wellbeing expenditure) has been converted into individual budgets. This is a very significant change. But there will be new challenges and opportunities for Barnsley as it explores the relevance of self-directed support in other areas:

If funding in these areas can be effectively individualised and control shifted either to the individual, to families or professionals working closely with the individual, then this would increase the scope of self-directed support in Barnsley by 200% and would mean that about £125 million (nearly 30%) was being controlled by citizens, rather than by commissioners.

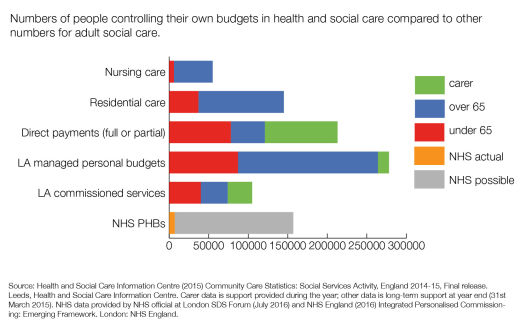

When we look at the national data we also seem the same pattern. Personal Health Budgets (PHBs) are being developed to offer more control to people needing long-term care. But why create a whole new system when there is already one in place for personal budgets?

Figure 3. Progress on Self-Directed Support in England

To date Government sponsored efforts to create ‘integrated’ budgets from multiple sources of funding have all tended to fail. Each system is unwilling to give up real control to the citizen or to the other partners. But, as the figures above indicate, there seems to be no good reason for having more that one system of self-directed support for Barnsley.

Although any such system will need to include a range of options and flexibilities, there is surely a good case for putting self-directed support at the centre of the integration and creating:

Ultimately the following funding streams are all likely to be convertible into personal budgets:

It would surely be very wasteful and stressful to have different systems for each of these arrangements. For example, it would lead families with complex needs to manage several different budgets, with different rules and negotiating with different professionals. This seems like an unnecessary mistake. Self-directed support provides an opportunity to integrate support in the most immediate way - through the leadership of the citizen and family. There is no obvious reason to have multiple systems of self-directed support.

One policy challenge hangs over this whole issue. For some critics fear that Personal Health Budgets will put us on the slippery road to privatisation and the use of insurance principles. Quite rightly such critics point to the immoral use of means-testing in social care as an example of what might creep into the NHS. So, there seem then to be three alternatives before us:

I suggest Option 3 is the only credible and progressive option and the Centre will work to advance this option in the coming years.

Alakeson V (2010) Active Patient - the case for self-direction in healthcare. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform

Block S, Rosenberg S, Gunther-Kellar Y, Rees D and Hodges N (2002) Improving Human Services for Children with Disabilities and Their Families: The Use of Vouchers as an Alternative to Traditional Service Contracts. Administration in Social Work, Volume 26(1)

Cowen A Murray P and Duffy S (2011) Personalised Transition: A Collaborative Approach to Funding Individual Budgets for Young Disabled People with Complex Needs Leaving School. Journal of Integrated Care, Vol. 19 Iss: 2, pp.30 - 36

Duffy S (2011) Dying with Dignity. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Duffy S (2013) Imagining the Future: Citizenship. Glasgow, IRISS.

Murray P (2010) A Fair Start. Sheffield, Centre for Welfare Reform.

The publisher is the Centre for Welfare Reform.

Real Integration of Health & Social Care © Simon Duffy 2016.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

health & healthcare, social care, Article