Part One in a new series of articles looking at Britain's crumbling education system.

Author: Gary Hammonds

Britain's education system is in disrepair, in a new series of articles, Gary Hammonds explores how we got to this point and how we can fix Britain's education system.

The central assertion of this series of posts is that the system of education in England ‘requires improvement’. That language, co-opted from the language of Ofsted inspections and reports, is central to the argument: the choice to marketise and privatise the education system, and the establishment of means of surveillance and control typified entirely by Ofsted, is entirely the problem. Each will be a standalone piece, but this article functions as an introduction for anybody with the time and inclination to read the whole.

This is not an argument that disparages teachers. Far from it: the argument, broadly, is that the political class has failed to create the necessary conditions in which the teaching profession’s efforts can best result in high-performing children and young people. This is also certainly not an argument that disparages those children and young people themselves. Instead, it argues that those who would most benefit from, and who would be most easily reached by, systemic improvement, are those that the current system ignores.

It is also not a defeatist argument. Inherent in the ‘requires improvement’ phrasing is the idea that things can get better. Starmer’s government and Phillipson’s Dfe have made some strides, notably the commitment to overcoming material disadvantage through the free breakfast club scheme. These efforts, amongst others, are to be welcomed. And there is an ongoing curriculum review, which seems encouraging, and ongoing discussions around Ofsted reform, which seem less so. But sadly, too much of this is tinkering around the edges of a fundamentally broken system. The system has evolved piecemeal over an incredibly long period, as is often the case in British politics.

What is required for such a disjointed and broken system is someone willing to expend political capital, really gripping and reshaping it. Nobody yet appears willing to do so.

Nigel Lawson said:

“Genuine educational reform is a particularly unattractive prospect for any government… It upsets all those with a vested interest … [but the benefits] will not become apparent within the lifetime of even the longest-lived administration.”1

He was, and remains, right. This truth explains the shoddy nature of some policy work in this field, with short-sighted politicians chasing electoral gains or personal political capital. That said, there have been numerous instances of politicians brave enough to do what was right, even when that was difficult, and when the incentives to do so were moral and long-term rather than tangible and immediate. In short, we need to aspire to good policy rather than good politics.

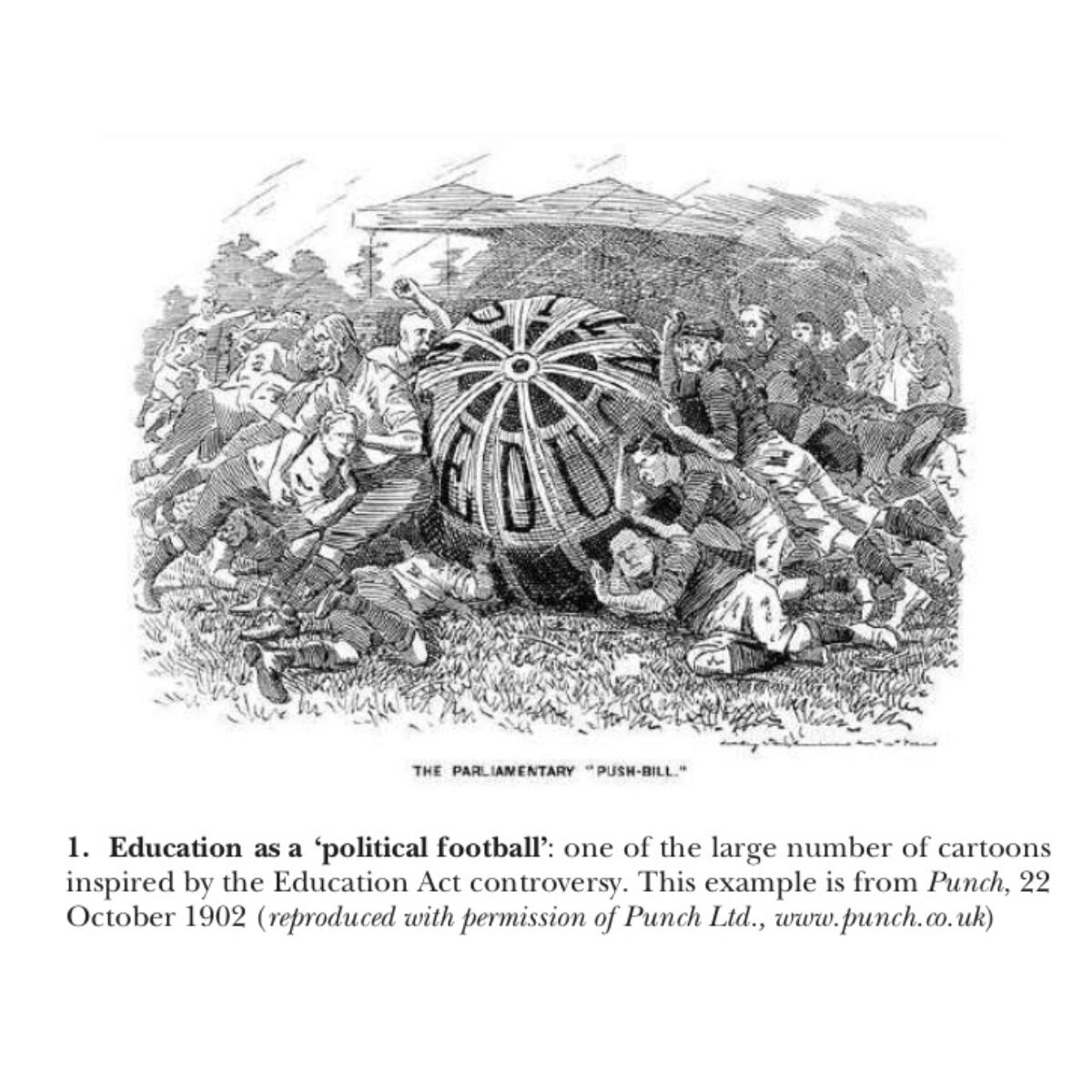

Illustration: Punch, 22 October 1902

Before improvements can be made to the system, a full understanding of why that system is as it is must be secured. This makes up the next post. There is a sketch of English education policy history which tracks developments up to 1988. The sketch ends there because 1988 undid the post-war consensus, dismantled the welfare state, and set English state education off in an entirely different direction2, pursuing:

The New Labour government, the coalition government, the subsequent Conservative governments and the present Labour regime have not deviated in any particularly principled terms from the 1988 Education Reform Act. This marked the turning point where the post-war consensus was rejected, and defines the system we currently face.

Before improvements can be made to the system, a proper diagnosis of its present shortcomings is essential. This makes up the following posts. There will be a crossover between these loose groupings, but the failures highlighted cover:

In its most condensed form, the argument is that education should create a population which is knowledgeable, skilful, and happy. The current arrangements are failing to deliver.

Before improvements can be made to the system, policy proposals need to be carefully considered with regards to moral purpose and practical implementation. Posts will include some such reflections and policy recommendations, but are ultimately designed instead to properly frame the thinking in that space.

This is not an argument for the return to some fictionalised and romanticised halcyon days. Rehashing political debates from the 1970s and 1980s serves no purpose. We need to take stock of the current lay of the land and move forward.

Education is a public good, communally owned. It has been, despite this relatively non-contentious declaration, surrendered to market logics and corporate purposes. It has been atomised, individualised, and is conceptually driven by competition. It is a neo-liberal project, controlled with the tools of New Public Management. The logics of markets, the approaches of business, and the interests of private capital – not one of these is an appropriate mechanism for handling public goods and services.

Schools, colleges and universities are a vital part of the civic ecology in England, and there is a need for a properly social democratic advocacy of them better fulfilling their potential roles in a highly functional society. This series is an attempt at such advocacy.

1. The View From Number 11: Memoirs of a Tory Radical;Nigel Lawson, Biteback Publishing, 2011.

2. Coalition Education Policy: Thatcherism’s Long Shadow; H. Stevenson, FORUM 53, 2011.

The publisher is Citizen Network. Britain's Crumbling Education System. Part One: Requires Improvement © Gary Hammonds 2025.

education, Inclusive Education, politics, England, Article