Simon Duffy wonders why progress to inclusion seems to have stalled and sets out the case for personalised support.

Author: Simon Duffy

Many years ago I had my eyes opened to the wonderful diversity of the world by people with learning disabilities and their allies. Over the years my friends, particularly Wendy Perez, Gary Bourlet, Simon Cramp and advocates like John O’Brien and Pippa Murray have challenged my thinking and helped me to see the value of a world where everybody matters.

The first step to inclusion is to leave behind tired prejudices. We don’t have to believe that clever people are better than other people. We don’t need to value one kind of beauty. We don’t need to keep chasing money and power. We can choose love, acceptance and diversity. These values may not be dominant - but they still exist deep within us - because we each know our own frailty, vulnerability and need for love and meaning.

These ideas continue to inspire a worldwide movement to advance the cause of inclusion for people with learning disabilities. But this movement rarely gets attention from the mainstream media or from policy-makers. Although people with physical disabilities have been successful in challenging and breaking down many of the major barriers in our way, the benefits of change don’t always seem to reach other groups.

People with learning disabilities, people with mental health problems, older people, people with chronic illnesses and many other groups are still treated as if they are too disabled to be empowered, too different to be included and too vulnerable to be free. For instance, if we examine spending on public services, the vast majority of funding still goes to subsidise institutional and segregated care. Sometimes the names of these services have been ‘modernised’ but in reality institutional power often continues inside ‘supported living’ services or ‘day activity programmes’.

We have, however, seen at least two important breakthroughs for the cause of inclusion. First we have seen, around the world, the advance of innovations like personal budgets, individualised funding or self-directed support. And it is not just people with physical disabilities who are benefiting from this change. Many other people, especially when they have support from peers, friends or family are finding that they can take control and can contribute to their communities - not only ‘like anyone else’ - but often better than anyone else. People with disabilities and their families are often super-citizens - transforming their world and the world around them.

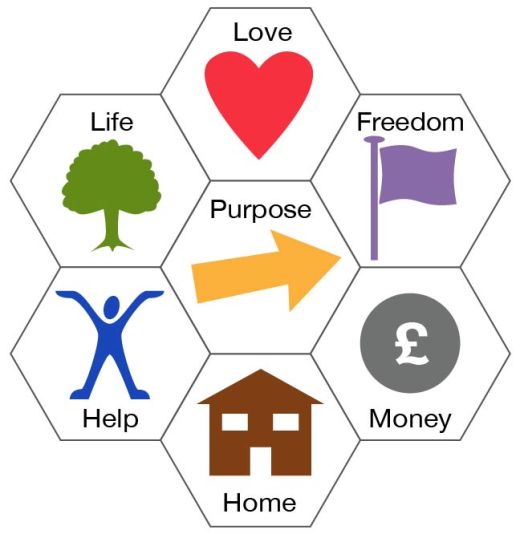

Second we have seen some professionals and service organisations start to change how they work. They recognise the authority of the person and their family and they work to enhance the person’s ability to live as a full citizen. Although this is jargon I still refer to this kind of support as personalised support and it usually has these characteristics:

This kind of personalised support does exist. I have seen different versions of this around the world and it has survived as a way of working for well over 20 years - often despite cuts in funding and damaging government policies. The best organisations have continued to cherish and support citizenship and to master the creativity necessary to support people who others have failed, abused or institutionalised.

7 Keys to Citizenship

The question that continues to trouble me is why it has been so hard to extend these ways of working to more people. Treating people as individuals, respecting them and working in partnership with them, is not just the right thing to do - it is incredibly effective even on the terms set by the current system. People are safer, healthier and happier. Yet this has not been enough to move things forward.

I suspect that this must have been what it felt like in the days before the great big institutions closed. There were many people then who knew that good support could be offered in the community; there were many people then who knew that institutions were bad for people. But it still took decades to close the big institutions and in many countries these big institutions still exist.

So, how can we take the next step towards inclusion?

How can we move from a few examples of good practice to major social and economic change?

These are big questions, requiring complex answers. Personally, while I may have some ideas, I still cannot fully comprehend the degree of institutional resistance which people with learning disabilities and other disadvantaged groups face. It’s almost as if we just don’t want to do the right thing.

However I think we can act and we can move forward. One simple action that we can take - in an increasingly interconnected world - is start to notice where good things are actually happening. One block to change is that the best stuff seems invisible. And if people can’t see something they tend not to believe in it. For this reason the Centre has decided to try and help move things forward by mapping and measuring international progress on personalised support.

We have published a survey which we are going to run for several weeks and which will help us track who is doing personalised support, for whom and where.

http://bit.ly/Personalised-Support-Survey-2016

This information will help us create a real map of innovation and allow us to begin to identify the best path for progress. It will be a clunky and imperfect process to begin with. But once we have identified organisations on the journey to personalised support, we can connect, learn from each other and help understand the barriers we face and how to overcome them.

Please, if you are part of any organisation big or small that is trying to advance inclusion and citizenship - whether for people with learning disabilities or for other groups - take this survey. Let us know how you are doing so we can all begin to appreciate the progress we’ve made and the progress we still need to make together.

The publisher is the Centre for Welfare Reform.

Next Steps on Inclusion © Simon Duffy 2016.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

disability, education, intellectual disabilities, mental health, social care, Article