How can we help people to take control in a system of self-directed support.

Author: Simon Duffy

This short article was written for my friends in Spain who are working to develop systems of self-directed support. They are at an early stage; but already they are thinking deeply about what these changes really mean. They understand that self-directed support and personal budgets will not transform our lives or our communities. But they are systems that can make such a transformation easier - but the work remains to be done - and the work is ours - all of ours.

Self-Directed Support is not a tightly defined model. Instead it is a broad term used to describe a system of interconnected parts that together enable people to organise their own support. There are different systems in different countries and no system is obviously the best.

The system should be flexible enough to work for everyone, whatever their needs, their age, family, circumstances and objectives. Not only does it need to be flexible enough to work for everyone it also needs to help people lead diverse and creative community lives. One system for many people, but one system for many outcomes.

Given this it is perhaps natural that there are competing ideas about how best to help people take control of their budget and their support. These competing ideas can also be the objects of passionate loyalty. Here are just a few different models (my apologies for any I’ve missed):

There are many different models, but what does the data show?

Well as far as I can tell there is evidence that all of these kinds of system are very helpful; but there is no evidence that one system is much better than another. In this situation I think we need to be very careful about picking favourites. Maybe we would be better to think of this more as an ecosystem where all of these kinds of things are positive and helpful, but what we want to encourage, is not one solution - but rather, ongoing innovation, learning and social change.

Certainly it would be helpful to have more research in this area. But the existing research is often quite problematic. Researchers never really make significant efforts to distinguish the impact of the different elements of self-directed support. Instead researchers tend to bundle those elements together and then evaluate the impact of the whole system.

So, what should we do?

Well here are three ideas.

First we can treat ourselves as experimenters. Let’s not decide in advance which is the best system. Let’s not try and pick our favourite model. Instead we can treat the whole support system as made up of different variables whose impact we can evaluate. Let’s stay awake and keep learning.

If Spain is developing new approaches to allow people to do things differently then encourage people to learn from each other. Where possible gather data, but also expect many results to be dependent on context. Some people will benefit from different systems, depending on their circumstances. What might work well for someone with an intellectual disability with a strong and supportive family may be totally unrealistic for a woman fleeing abuse or for an older person who has become socially isolated.

We don’t need one solution. Plurality is positive.

Let’s not get locked into any one system. Strong commitments to particular systems, in a situation of uncertainty, are more likely to lead to mistakes that are painful, expensive and time-consuming.

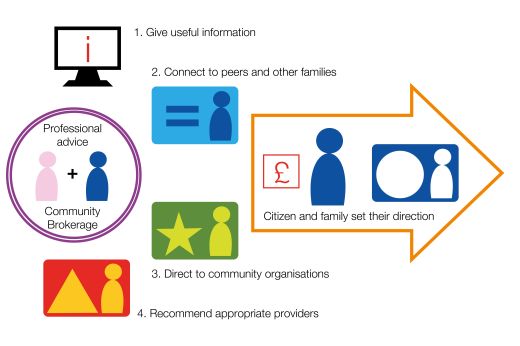

A few years ago my colleague Kate Fulton and I wrote a paper called Architecture for Personalisation where we tried to explore how to use the political options available to enable people a range of different support options. We called this broad system of possible supports Community Brokerage and we encouraged municipalities to use all the resources available to them. You can get an idea of what we outlined in the attached graphic (see Figure 1).

I am sure that this won’t apply perfectly in Spain, this model is developed in the context of the specific English context. But I am sure that in Spain you can apply the same kind of philosophy to explore how to maximise the available options.

Figure 1. Community Brokerage

This is also a political issue. Not party political - but professional political. An approach which says some people can help people plan and organise assistance and some people cannot has two obvious consequences. First, you limit the available assistance and make it harder to get people the assistance you need. So you slow down the growth in self-directed support.

But, second, you also run the risk of raising up the status of one group of professionals (or may be non-professionals) and pushing down the status of others. Effectively you will be saying to some people:

“You are not trustworthy or skilled enough; you must let other people do that work, your job is just to do some more limited work.”

In my experience this only creates bad feeling, resistance and serves to undermine the process. We need to release more capacity to provide the right kind of help and to work in an equal partnership with the person with disabilities. Creating higher status roles for some, and lower status for others, doesn’t seem like a good strategy for encouraging positive social change.

There are some things in life which are best handled by relatively simple and repetitive processes. We don’t want to have to improvise at every moment. We want reliable trains, energy services and financial security. So it is natural to start looking for the right model that we can standardise and role out.

But life is and should not be standardised. In fact a good life is always improvisation, bringing together our gifts and needs and engaging creatively with the opportunities and constraints that life brings our way. At its best self-directed support unleashes creativity within and around each person. We do not a world where are few people are the artists and the rest of us are merely spectators. Nor do we want a world where people believe that they cannot be creative and don’t feel they have the means within themselves to live the best life they can.

So let us think about what might inspire creativity in self-directed support. Here are just a few ideas:

We need to design our approach around an assumption of capacity, not incapacity. Professional input and assistance will be necessary for some people, especially in a crisis, but we don’t want to organise on the assumption that professional support is the only kind of support.

Most of all our belief in the value creativity should be a value that underpins all of our work. For this belief is closely connected to our view that every single person is full of potential and is capable of creativity and can make a positive contribution. These are the values of inclusion and of equal citizenship and they create the most important platform for the changes we need to make.

None of this is to suggest that offering people good support to plan and organise support is not important. It is important. Just setting up a system of personal budgets on its own will not lead to the changes we hope for. But if the values and skills of creativity are important then let us treat the necessary values and skills as important for everyone, not just for some special group.

Bartnick E & Broad R (2021) Power and Connection: the international development of Local Area Coordination. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform.

Brandon D & Towe N (1989) Free to Choose: An introduction to service brokerage. London: Good Impressions.

Duffy S (2007) Care Management and Self-Directed Support. Journal of Integrated Care, Vol. 15 No. 5, pp. 3-14.

Duffy S & Catley A (2018) Beyond Direct payments: Making the case for micro-enterprise, Individual Service Funds and new forms of commissioning in health and social care. London: TLAP

Duffy S & Fulton K (2009) Should We Ban Brokerage? Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform.

Duffy S & Fulton K (2010) Architecture for Personalisation. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform.

Fulton K & Winfield C (2011) Peer Support. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform.

Keilty T (2020) Adventurous Social Work? Using resources differently with Look After Children and their families - some early lessons from the Scottish pilot sites. Glasgow: In Control Scotland.

Leach L (2015) Re-Imagining Brokerage. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform.

O’Brien J (2001) Paying Customers are Not Enough: The Dynamics of Individualised Funding. Lithonia, RSA

O’Brien J & Mount B (2015) Pathfinders: people with developmental disabilities and the allies building communities that work work better for everyone. Toronto, Inclusion Press.

The publisher is Citizen Network Research. How to Make Control Work © Simon Duffy 2022.

Self-Directed Support, England, Spain, Article