Further measures on car use must be taken now in order to meet the UK’s overall net zero emission target by 2030.

Author: Philip Adams

In a previous article Electric vehicles - good or bad, we provided readers with an introduction to the benefits of using an electric car. It concluded that, by using the improved technology of electric cars and displacing cars with internal combustion-engines, their emissions of CO2 that are contributing to climate change could be reduced.

This article goes further - to show that a change to electric car use is not enough if we are to meet the country’s overall net zero emission target by 2030, nor to reduce traffic congestion. Further measures concerning car use must now be taken. These measures can be best understood by considering electric cars within the full process of transport decarbonisation and the role of car sharing. The process is represented in similar ways in Figures 1 and 2, immediately below and later.

Transport, with 28% of all emissions, is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the UK.

Figure 1. How to decarbonise transport

The purpose of transport is to get to an activity or a place to achieve a particular task or objective. Historically, transport planning has been supply-driven and reactive. That has meant that the response to traffic increases was to supply more roads. By attempting to meet an ever-increasing demand in this way, our desire for mobility has created even more traffic, more energy consumption and a less liveable and wasteful environment. This is the point made in the ‘armchair’ quotation.

The average annual kilometres travelled per person in the UK in a car/van is 11907 (down from 14802 since 2002); 2333 on foot; 1255 by train; 595 by bus; 80 by bike and 80 by motor bike).

From top to bottom, in order of preference, each band of the inverted pyramid in Figure 1 represents ways of decarbonising transport. The key question represented by the pyramid is: can the need to travel be reduced? This may refer to the length of a trip, or to the frequency with which a trip is carried out. Both will reduce emissions. Therefore, reduction in the need to travel is the first step to consider before deciding what mode of travel is best and before improving the efficiency of the mode of transport or vehicle.

A large majority of UK Climate Assembly members favoured a better type of planning, known as localisation, to avoid unnecessary emissions. Localisation requires that new housing can only be built where good public transport links are included, along with good local services such as schools, post offices, shops and health centres.

In 2018, 61% of trips and 77% of the distance covered in England was by car. 10% of car trips were for less than 1.6 km (a mile). Out of the 800 trips covered per person that year only twenty-three were walks

Where the avoidance of journeys is not possible, using a less damaging, friendlier, form of transport-going by train or bus, walking or cycle are the preferred alternatives for necessary journeys. Friendlier means choosing a mode of travel that emits fewer emissions per traveller kilometre by using less fossil fuel energy.

To carry out a friendlier journey, it may be necessary to shift from one mode of transport to another, or to combine several of the modes shown in the pyramid. For example, taking a bus instead of driving a car to the rail station or, even better, walking there. In such cases, the closer each mode is to the top of the triangle the better, for reducing emissions. Therefore, only when unnecessary journeys have been dispensed with, and the ‘friendliest’ travel modes have been selected, may it be justifiable to consider car sharing or improving the efficiency of the vehicle itself by changing to electric.

In recent years people in the UK have been flying more both domestically (20% of total) and internationally (80%). Aviation accounted for a quarter of transport energy demand in the UK in 2017 and 7% of greenhouse gas emissions. Much of this is avoidable. In the short term we must improve aviation fuel’s use per passenger kilometre and stop non-essential freight movement by air, pending the introduction of electric or hydrogen planes. In France, non-essential short-haul internal flights have been banned, where train alternatives exist, in a bid to reduce carbon emissions.

74% of UK households have a car. The UK’s 31.9 million cars and 4.2 million light goods vehicles account for 66% of transport emissions and 50% of all transport energy. Each household owns an average of 1.2 cars. When used for commuting, the average occupancy is just 1.16 persons.

Whilst average annual car ‘mileage’ in England reduced almost 20% from 2002 to 2019 with a decline in CO2 emissions, 2019 saw the third consecutive yearly rise, so the absolute tally of transport emissions has not reduced. The increased proportion of petrol cars, and ‘sports utility’ vehicles, being heavier by some 30kg is the reason for the rise.

Until recently much attention was paid nationally to improving the energy efficiency of the internal combustion engine because it is just 17-21%, compared with the 90-95% of a pure electric car.

Cars spend 80% of their time parked at home and 16% parked elsewhere. We should therefore already be considering the economic inefficiency of car ownership for that reason, before considering their impact on C02 emissions, pollution and congestion.

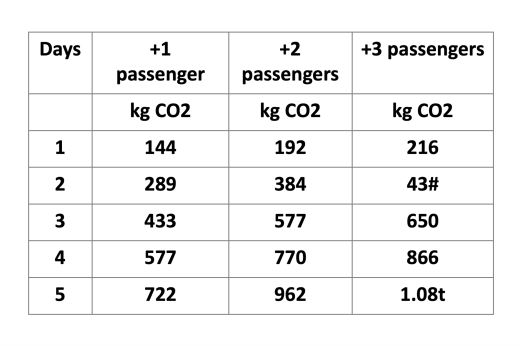

A greater proportion of local journeys should be made on foot or by bike, whilst longer distance journeys can be made by rail or coach, and car-sharing. Sharing journeys, even with internal combustion cars, can be beneficial as shown in the example in the table below. The preferred measure of efficiency for emissions reduction is CO2 emissions per passenger kilometre. This refers to a return journey of 11.3 miles (18.2km) each way. It is assumed that the one car being shared emits 171.1 g CO2 per passenger mile (106 g CO2/km) during single occupancy. And that 232 days are travelled per year.

It shows how increasing the number of passengers per journey, from 1 to 2 to 3, reduces the emissions per passenger kilometre with each increase:

Table 1. Reducing emissions by car sharing an ICE car

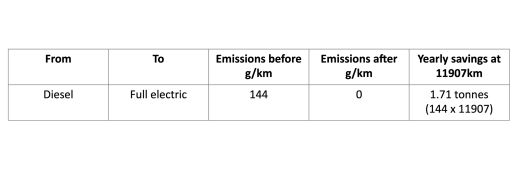

By replacing an internal combustion-engined (ICE) vehicle with electric, its improved technology will reduce emissions to zero. The reduction that can be achieved during the annual mileage of the average UK car driver (11907km) in a typical car is shown below.

Table 2. Reducing emissions by converting to electric

If the electric car is shared by others, who would normally do the journey in an ICE vehicle, there would be further savings, arising in the same way as for sharing ICE cars.

Emission reductions are also being achieved by lower carbon fuels such as E10 bioethanol in petrol and fitting pollution technology to ICE vehicles. Today, the order of preference (worst first) for choosing the vehicle’s fuel type is to use: 1. Petrol or diesel;2. Plug-in hybrid; 3. Hybrid 4. Electric rather than Plug-in hybrid; Hydrogen fuel cell technology rather than electric.

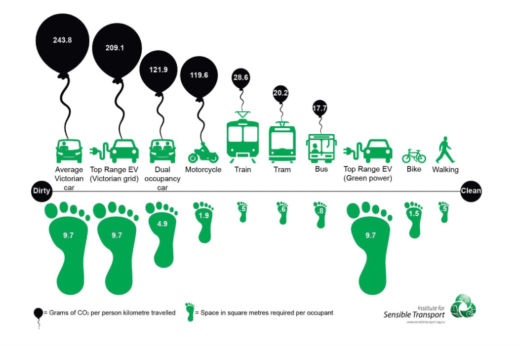

Figure 2. Decarbonising transport and reducing congestion,

Figure 2, from the Institute for Sensible Transport, contains two important messages about decarbonising transport modes and congestion, one above and another below the line.

From left to right it shows the worst-to-best modes of transport as far as CO2 emissions are concerned.

The size of the footprint indicates the space per person taken up by the mode of transport above it.

A fine plan for encouraging modal shift, mainly from car to car-sharing and car to public transport, is taking shape in south Wales to alleviate intolerable traffic congestion in the Cardiff to Newport area. The South Wales Transport Commission plan is encouraging employers to create workplace travel plans, remote working from flexible hubs, and installation of parking restraints at workplaces.

The change will be encouraged through a combination of infrastructure investment, policies such as affordable fares and integrated ticketing across all services and co-ordinated bus-rail timetables. Land use and planning will centre on public transport, not the motorway. Interchange points will mean that 90% of the populations of Newport and Cardiff will live within a mile of rail or rapid bus route. Early improvements in walking, cycling and bus services will be followed by rail after five years. A single brand will publicise all services.

Sharing increases the occupancy of a car and reduces the car’s emissions per passenger kilometre. Community transport and Demand Responsive Transport is, in effect, sharing on a larger scale. Community transport groups traditionally were independent charities or voluntary organisations for people who may not be able to use, or have access, to public transport. They help individuals and groups get to events such as sport or theatre that would be otherwise inaccessible. Demand Responsive Transport is more flexible in which a provider responds to the traveller’s specific journey request on demand via a phone call or, more usually, digital communication.

Going by bike instead of car is an example of shifting to a healthier and more environmentally beneficial mode. Cycling also enables longer journeys than walking. Also, the improved technology of electric bikes enables longer, or more difficult, trips to be made, further reducing the need to make shorter journeys by car.

Walking and wheeling are most suitable for shorter and more frequent local journeys. A generation ago it was normal for 70% of UK children to walk to school, either on their own, with friends, or accompanied by an adult. Today’s figure is just 53% as more and more students are dropped off at school by parents using cars. One in four cars on the road in the morning peak is on a school run; important when congestion is considered. Even though journeys sometimes involve sharing a rota with other parents, the ‘school run’ is more wasteful than a worker commuting because it normally involves a double journey, both to drop off and to pick up.

There are several reasons for this trend. In many cases both parents work and do not have time to walk their children to school, and do not know any other parents who have the time. Even if the children are old enough to walk on their own (or cycle), most parents are more worried that something may happen to them, such as an accident, than considering the health value of walking. Often, however, where the distance is too far for walking there is no convenient bus service.

This raises the importance of introducing individual School TravePlans). ‘Swap the school run for a school walk’ sets out how school leaders and staff can discourage the use of cars to bring children to school and encourage cycling and walking where possible. The school run should only occur when car use is unavoidable.

The top band in Figure 1 refers to working or studying remotely by communicating digitally with clients and work colleagues via internet platforms such as Zoom. This reduces the amount of travel and likely means a reduction of CO2 from the mode of transport previously used. By using digital communication in this way, one has avoided the need to travel and reduced CO2 emissions. This is a change of behaviour that may lead to a reduction in CO2 emissions. Living closer to where we work has the same effect.

During the Covid 19 pandemic the value of travelling to a common destination each day was questioned. Many organisations, employers, self-employed and educational bodies realised that commuting could be reduced, particularly during the pandemic, by introducing measures such as the four-day working week. Others questioned the journeys they made for leisure and concluded that, when things returned to normal, only necessary journeys should be made, and by less carbon-intensive modes such as car-sharing.

Changing the behaviour that creates the desire for car ownership and removing the barriers that deter more trips being made by car sharing is not an easy process because it involves actions by the Government, Local Authorities, private bodies and individuals. That action on climate change can improve quality of life for all is the message to convey. In addition to CO2 reductions, the benefits of car-sharing are economic, health and resilience improvements. Yet even people who accept these as true benefits and intend to take advantage of them often end up not doing so, even when they can. We must ask why?

Firstly, when we have a lot to decide we often take the easiest decision, not the best. We also tend conform to what others are doing, regardless of what is best for us. When assessing what is best for us, we consider immediate gains and losses and deny ourselves greater future common benefits.

Such biases take individuals away from rational decision making. If we were always rational, we would choose to adhere to regulations, respond to economic incentives and set our preferences and attitudes on objective information. Therefore, something else is also needed to get people to do the ‘right thing’.

Both municipal and private organisations have roles to play in changing their own behaviour and encouraging others to do so. Organisations like Sustrans, the Energy Saving Trust and the Local Government Association can help them to make such changes as introducing the Workplace Parking Levy, car share schemes, vehicle electrification and travel plans.

Some drivers are beginning respond to the financial effects of commuting by car alone, realising that they are spending approaching £5,000 a year and underestimating total vehicle costs by about 50%. simply to own a fast-depreciating asset. The annual cost of running a car is calculated as 20% of annual gross disposable income That’s why many are starting to employ the idea of UDO: Use it; Don’t Own it!

In a recent German study, providing personalized information on the costs of car ownership increased respondents’ willingness to use public-transport by around 22%. Educating people about the true cost could reduce car ownership by up to 37% and cut associated transport emissions by 23%.

The House of Commons Climate Assembly UK’s views are indicative of the current attitudes towards the climate crisis and the potential for transport behaviour change. 86% of members of the Assembly agreed that steps should be taken to encourage lifestyles to be more compatible with reaching net zero. The Assembly’s first principle for net zero was to inform and educate everyone (74% of votes). The key recommendation on transport was to minimise restrictions on travel and lifestyles ‘placing emphasis on electric vehicles and improving public transport rather than large reductions in car use’. How this reduction should be achieved is implied in some of the votes taken, in which:

Substitution of the car by improved public transport was a general desire: 91% supported low carbon buses and trains, 86% new bus routes and more frequent services and 86% cheaper public transport. The Assembly invoked the principle that the ‘polluter must pay’, that measures should be accessible and affordable to all sections of society if significant changes are to be achieved by individuals. Other changes may have to come from the ‘stick’. One important possibility is road pricing.

Where is all this leading? The idea of mobility without the ownership of vehicles is growing. This is not a new idea: the use of taxis, traditional car or van hire and car clubs are examples of mobility without ownership, where separate services are provided for each means of transport. There is no integration of the services in any form. This is the situation that preceded mobility as a service, or MAAS. As far as passenger transport is concerned, MAAS also embraces all the modes shown in Figure 2. Whilst it is multi-modal transport, MAAS includes an important addition to make any necessary movement from place to place a more efficient and a more pleasant experience.

Its final form integrates various forms of transport services into a single mobility service, providing access on demand by means of three main components:

Finally, MAAS extends beyond liaising between the demand for and supply of mobility. The added value is the reduction of private car ownership and use, thereby promoting a more accessible, liveable environment. At this level the MAAS project integrates societal goals. For it to work, the integration of search, book and payment functions of mobility service in a given service area is the minimum. Public transport forms the backbone of the MAAS infrastructure and is complemented by other mobility services like taxi, DRT and bicycle sharing etc.

Individuals can do certain things to mitigate climate change. MAAS will do much more to help us to combat it more effectively as far as transport emissions are concerned. That is because it requires the sort of collective actions embodied in MAAS to do it.

The publisher is Citizen Network Research. Electric cars, Sharing and Decarbonising © Philip Adams 2022.

community, Sustainability, England, Wales, Article