Instead of focusing on a problem as a problem convert it into an opportunity for community.

We might be talking about poo here, but if you read this story, the moral of the tale could apply to most scenarios.

If we grow power, and resources don't shift with it, then we are servants of the master, rather than powerful communities exercising community functions.

Here’s a story to illustrate what we mean. It’s been shared by one of the caretakers of the movement, Angela Fell, who lives and works where she lives in Springfield, Beech Hill and Gidlow CommUnity in Wigan.

“We started to connect the local community (about 13,000 people) just before lockdown. It really opened our eyes to the idea, and now dream in action, of becoming a self-organised and self-renovating community. Across the area, we discovered that once connected, we had much of what we needed. And what we didn’t have, we knew who to ask or where to get it from. We did lots together during the pandemic aside from the usual types of support. We thought that the pandemic provided an opportunity to nurture a more connected community, and one that makes decisions together. We encouraged discussion and debate on the local group (which for the first year was mainly online) and practised the long lost art of agreeing to disagree, speaking about our opinions rather than from them. We started to raise bits of money together too and make decisions together about how to spend it – like a really small and local participatory budgeting practice.

Concerns around the amount of dog poo in the area and some concerns around fly tipping became a pretty regular conversation. So, the community members who were interested in cultivating community put their heads together. It was a dilemma as the plan was to keep the community group focussed on what’s strong and everyone seemed to be talking about what’s wrong.

As often happens when a group gathers, an idea grew out of the conversation.

What if, we chatted to the Council and asked them for the local statistics and costs of clearing dog poo in our community. Then, we could share the statistics with the community. We held the view that an informed community would want to shift this kind of spend to something more fruitful in the local area. We thought that we could save money and, with the Councils agreement, we could keep 50% of any savings for participatory budgeting. We wanted to turn poo into power.

And right there, ‘a rubbish idea’ was born. We wrote to our local Council Officer, the Service Delivery Footprint Manager (a title that makes little sense to most people around here) with ‘A Rubbish Idea’, and it’s fair to say he loved it! He said he’d pull a meeting together. It took a while as they wanted lots of different departments to attend.

Eventually we met. We were offered litter pickers to clean up the area. We were advised of ways of reporting serial offenders. We were offered dog poo fine warnings sprayed on the pavement. The elephant in the room was money - the shifting of resource. When we asked, the online Teams room went silent. ‘There might need to be another meeting about that.’ We listened, and returned to our circle to ponder. To us, it didn’t feel like the ideas would connect the community or contribute to the local vision and dream. Maybe it was because all the early intervention people had been lost to austerity, that it all seemed a bit enforcement based – a bit like ‘shop’ your neighbour rather than talk to your neighbour. So, we pondered some more. We knew it was important to let people know what the last resort enforcement options were, but not before the work of the community was done. The Council isn’t our parent after all.

At this time, we’d also be out and about in the community, having conversations in the parks and on the streets and one of the things we’d been beginning to notice was that people loved their dogs, and that there were little communities of dog walkers all over the place. And another idea was born as we listened to each other.

Let’s have a dog show. We can use the money raised to do something positive about the dog poo problem. The Springfield Dog Show was born.

Meanwhile, in the midst of all the excitement, we’d remembered we had still to hear from the Service Delivery Footprint Manager about the money - shifting any savings towards a community participatory budgeting pot, so we gave them a nudge. They contacted the Director, who didn’t respond directly to us, but back through the Service Delivery Footprint Manager.

“In terms of funding, the costs associated with removing fly tipping, littering etc are contained in a wider street scene staffing budget and any support the service receives via volunteering will not directly save the council money, it just allows the staff to concentrate on other key work that adds value to our local environment. To realise any notable saving in this area it would require significant and sustained behaviour change, which we hope to achieve overtime once we launch our new littering strategy in September 2021.”

We felt a bit frustrated by this response. The wise words of Desmond Tutu sprung to mind.

“I am not interested in picking up crumbs of compassion thrown from the table of someone who considers himself my master. I want the full menu of rights.”

Desmond Tutu

We decided to just do it anyway. As it is, Springfield Dog Show is now in its second year. Money raised pays for dog poo dispensers and poo bags. Streets nominate themselves for dispensers. Nominated streets agree to keep the dispensers filled and join a WhatsApp group of other committed folk.

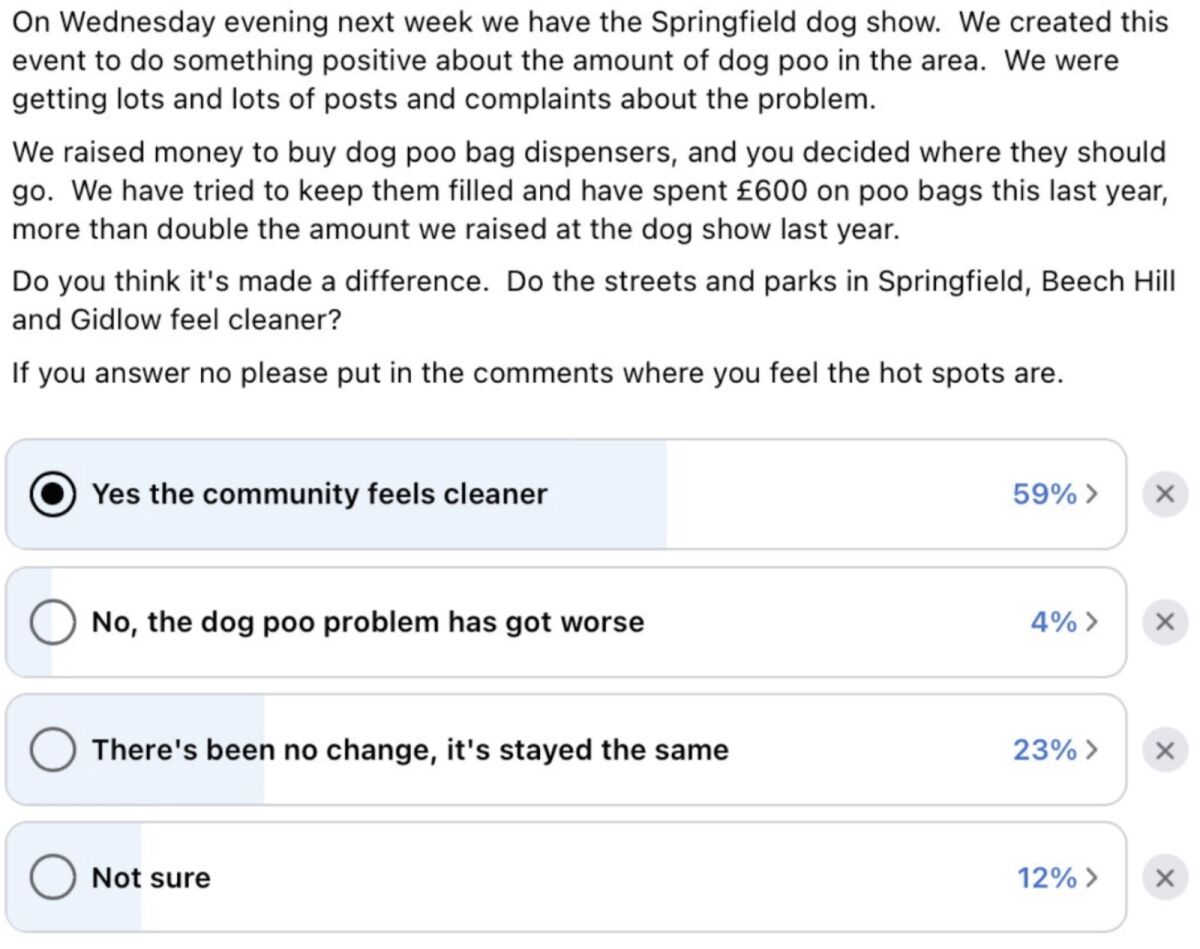

The show has become a real community affair, with sponsorship from local community minded businesses growing all the time. And it’s making a difference too, according to the members of our online community. (2,374 members across an electorate of 9,049, where the elected member secured 1,542 votes to sustain the seat)

You can read about it here if you like. People seem to enjoy being in community together.

Whilst we did it ourselves in the end, that’s not the point. Communities want more than the power to influence or shape. We want the resource too, that’s got to shift too.

Here in our small community in Wigan we are really thankful to have Lankelly Chase GM System Changers investment, but that’s not going to last forever. We aren’t volunteering, we are intentionally and thoughtfully community building and stepping into our citizenship, reclaiming the functions we’ve forgotten belong to us. That requires resource. Part of the local work includes exploring community alternatives to care, in order to end the extraction of children and wealth from our neighbourhoods. As we grow, will we be thanked for our ‘volunteering’ and politely informed that this has enabled staff to focus on other key work, like producing strategies for us, without us?

I mean, that’s not going to cut the mustard and that really isn’t community power. It’s community exploitation. We saw this happen during the austerity years. Fantastic community initiatives were often cut, based on their funding source whilst services and some people within them who had been stealing a living managed to survive. This will happen to the community power agenda if we don’t make brave decisions around where it sits and who holds the resource.

At NDM we are orienting ourselves towards beyond reform, one of the social maps created by the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures collective.

As Vanessa Muchado de Oliveria describes in Hospicing Modernity

“The beyond reform orientation recognises that the redistribution of resources within existing institutions, will not in themselves be adequate to shift the underlying violent and unsustainable infrastructure of the modern / colonial system.”

“This does not mean that immediate reforms to modern institutions - including redistribution and representation - are unimportant, but rather that ultimately these institutions cannot be reformed or redeemed, at least if the goal is to end colonial violence and unsustainability and enable different futures.”

Vanessa goes on to say that,

“It is important to note that beyond reform work is virtually unthinkable in most institutions where soft and radical reform are still important strategies for harm reduction.”

And we need more hackers, “those who work within the system to redirect resources from within towards nurturing something else.”

Will we see that happen when it comes to community power?

Where will the resource go?

Will the hackers get it out?

Will it seek to reform and redeem?

Will the gardens of the think tanks grow?

Will it be caught by the usual suspects?

Perhaps you have a story? Are you hacking or nurturing?

PROVIDED BY: Springfield, Beech Hill and Gidlow CommUnity

community, local government, Neighbourhood Democracy, England, Story