Simon Duffy on why a system of basic income plus an appropriate disability benefit would be a significant improvement over the UK's current system of demeaning conditionality.

Author: Simon Duffy

There is a growing campaign for basic income in the UK. What does basic income mean? Well it means that as a society we would commit to give each other an income that would be enough to live on, and that any income tax we paid would be on top of that. The reason why many of us like this idea is that it is a clear and powerful way to fight poverty and inequality. In addition it reduces the stigma, shame, damaging means-testing, conditionality and the complexity currently associated with the benefit system.

Nobody I know who advocates basic income believes it answers all the world’s problems, and it certainly leaves some important unanswered questions. One of the most important being what happens to disability benefits. However, many disability campaigners, who have tried to resist the UK Government’s direct attack on disabled people, believe that basic income won’t help them. Instead they want to either amend the current system or to develop a new system, not based on basic income.

Unfortunately there appear to be severe risks in defending the rights of disabled people in the wrong way.

If we are not careful we can frame the problem of disability benefits along the lines defined by the current UK Government. But there is no easy way to amend the current Employment & Support Allowance (ESA) system to without accepting two falsehoods:

The system is a mess and will remain a mess because its underlying thinking is muddled and immoral. The ESA system is an insult to human freedom and to basic human rights.

The underlying fallacy within ESA is the notion of the 'deserving poor' - the idea that some people deserve a better deal because they didn't somehow bring their own poverty upon themselves. We must utterly reject this concept. Not only because it is unfair to those who are deemed the 'undeserving poor' but also (as we've seen) it is extremely dangerous to those who are deemed deserving: it creates the suspicion of fraud, demands enormous interference and monitoring, and creates a sense of fear and unworthiness.

Moreover, trying to amend ESA also encourages us to engage with this Government as if it is rational and interested in justice. It is not. The UK Government is committed to ongoing attacks on disabled people. To the Government disabled people are merely a useful scapegoat. The current Government is not interested in rational debate nor in social justice. Offering them sensible and modest reforms is just an exercise in heart-break. They must be defeated and the terms of future debate must be radically shifted towards justice.

This is why it is a good time for radical thinking; it is time for basic income and, in addition, time for an approach to disability benefits that I will call Basic Income Plus. It is only by means of radical thinking that we can move this debate back towards something approaching sanity.

Here I want to briefly outline why Basic Income Plus could be a powerful and positive alternative approach, which can be adapted to take account of the reality of disability.

The most obvious advantage of basic income for everyone, including all disabled people, is that everyone is assured an income (perhaps close to the level of the state pension, £115 per week) without any assessment, complexity or means-testing. Even on its own such a system would replace a large part of the need for the ESA, which currently costs £14 billion and is received by 2.5 million people (an average of £108 per week). This would kill in one stroke the crazy and expensive world of conditionality, sanctions, privatised assessments and ineffective training programmes into which disabled and sick people are currently forced.

However basic income, on its own, will not be enough to ensure disabled and sick people are able to be full citizens. So what else is required?

The most obvious addition that will be a system for meeting the additional costs of disability. Previously this was met by Disability Living Allowance (DLA) and Attendance Allowance (AA) which is for over 65s. Both these benefits are now under severe attack, the former being ‘reformed’ into the opaque and mean-spirited Personal Independence Payment (PIP), the latter being stolen to subsidise the failing social care system.

In my view it is a huge mistake to transfer this money from disabled people into the hands of local government. AA and DLA were low cost and efficient ways to ensure that many people could meet the extra costs of disability. Its replacement will focus funding on fewer people, at greater cost, and will increase the rate of crisis within social care. This is will effectively make a crisis-driven social care system more crisis-driven and even less sustainable.

We need to return to a system along the lines of DLA, with clear benefit levels that are proportionate to need. This can be delivered as a non-means-tested and non-taxable disability supplement to one’s basic income and as part of a new integrated tax-benefit system. There is already a significant research literature identifying and calculating these extra costs.

Of course the key issue is how such benefits are claimed and validated. We know that the sub-contracting by the DWP of assessments to ‘independent' assessors has been disastrous. Assessments are full of errors, the process is wasteful and inaccessible. Moreover there is a strong suspicion that the DWP is pressuring assessors to corrupt the assessment process in order to push costs down further. The human cost is already being measured by an increased suicide rate.

However if we reject this model of assessment we must develop a new model in its place. The most straightforward would be to create a clear system in which people can claim the correct disability supplement for their circumstances, and have that claim validated by the relevant expert from the NHS or Social Services. GPs, social workers and others are already paid to carry out such assessments as part of their normal work; they are largely trustworthy and they already connected to the person. However there will need to be some checks and balance to protect people’s rights. I would also include a system which allowed for a more personalised approach to reassessment (perhaps varying time-limits for assessment dependent upon the nature of the person’s impairment).

However there are at least three other things to think about in developing a Basic Income Plus system. First we would need to decide how to provide a degree of additional income insurance for people who fall sick or who acquire a disability, cannot work, yet who who have got used to a higher income. Currently some of the ESA system is designed to pick up where Statutory Sick Pay leaves off and to give people who were earning time to adjust to a lower income.

Personally, while I accept that a limited degree of this kind of income insurance makes sense, particularly in our debt-ridden society, I am concerned that this is a regressive policy. When a University Professor falls sick it is not clear that they deserve a higher income than a personal assistant who falls sick. If there is a role for income insurance I think it must be a modest one and it would be best integrated into the tax system, as an extension of statutory sick pay, rather than being treated as a disability supplement.

There is however a much stronger argument for supplementing the basic incomes of disabled people, simply because disabled people are less likely to be in paid work and so more likely to be have lower than average incomes. This could be done by a taxable addition to the disability supplement. So all disabled people would get a taxable uplift to their basic income. So, someone not working, or only able to do limited work, would benefit more than a disabled University Professor.

The third element to consider would be how to deliver the kind of personalised support that is currently organised through personal budgets in social care, Access to Work, and which is also still available in Scotland through the Independent Living Fund. In a decent society we would still offer assistance to everyone who needed assistance to find work or to contribute in other ways. But this assistance would have nothing to do with the benefit system. It would be non-means-tested and there for everyone who needed it and wanted it. Some specialist assistance (e.g. high quality supported employment) would also be necessary. Personally I would integrate all of these funding streams into one system of funding for personal assistance and personal budgets, which would be managed locally, and combined with local community support, but which would be subject to robust national rights.

I also assume that carers entitlements would become additional elements for carers, and this would also need some assessment. But that assessment could also be linked to the relevant disability assessment for the disabled person. I suspect that a Basic Income Plus system with income supplements for carers that were non-means-tested, but taxable, would also be fair (however I may not have given this enough thought).

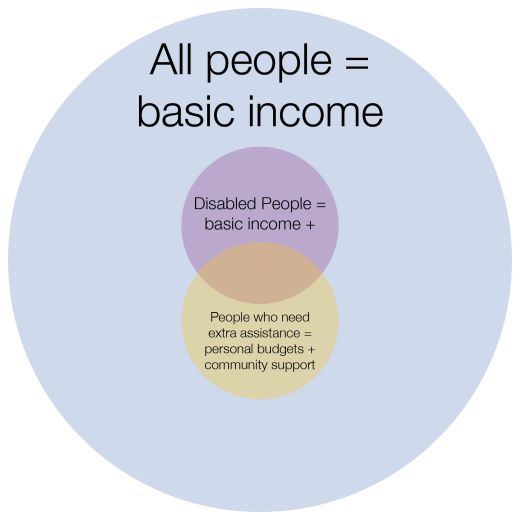

In the end this system would help us take a big step forward towards human rights for all, including disabled people. Nobody would be subject to demeaning systems of control and punishment managed by the DWP (whether they had a disability or not). Everybody would get a basic income. Sick or disabled people would get an appropriate supplement to that income. In addition we would organise any further support and assistance in a way which was empowering and under the control of disabled people themselves (see Figure).

The case for Basic Income Plus is both moral, strategic and technical. It is moral because it is a good way to protect the human rights of disabled people, which includes the need for an adequate and secure income, with no stigma and with no penalties for working, saving or contributing in other ways.

It is strategic because it links the fate of disabled people together with the fate of all people, those who are not yet disabled and those who may never be disabled, but all of whom have a stake in a universal basic income system.

Finally there is a technical consideration. Increasingly we will find that our incomes, taxes and benefits will all come together in one system. Even Government, which is terrible at developing IT systems, will end up adopting systems that talk to each other and where many of the old administrative distinctions will fall away. Increasingly we will need to stop talking about these jargonised and bureaucratic systems (PIP, ESA, ILF, DLA etc.) and start talking about the real issues: what income will people get, how much tax people will pay and when is it appropriate to increase income because of an impairment.

Duffy S & Dalrymple J (2014) Let’s Scrap the DWP. Sheffield, The Centre for Welfare Reform.

Wood C & Grant E (2010) Counting the Cost. London, Demos.

Wispelaere J de An Income of One’s Own? The political analysis of Universal Basic Income. Tampere, University of Tampere.

My thanks to James Elder-Woodward for helping me clarify my thinking. Jim is not responsible for any errors in my argument.

The publisher is the Centre for Welfare Reform.

Basic Income Plus © Simon Duffy 2016.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

Basic Income, disability, tax and benefits, England, Inspiration