Looking at the causes of institutionalisation can help us identify common goals in our efforts for social justice.

Author: Simon Duffy

For Berta González

It is encouraging to hear in some countries, like Spain, the COVID crisis has woken people up the significant harm that is caused by mass congregate living and the additional health risks faced by people in care homes. There is renewed interest in what we can learn from deinstitutionalisation processes and what we might do differently this time. This short piece is dedicated to our Spanish friends.

The term deinstitutionalisation is often used to describe the process of closing congregated care facilities and moving support services into the community. There has been some significant progress on achieving this goal globally, although it is also important to note how challenging and slow these changes have been.

Not only are institutions effective at resisting or delaying change; but often we find that the services that replace the big institution are also highly institutional. If we are not careful we can we put enormous energy into a process of change only to find that the final outcome fall far short of our aspiration or is not even sustainable. We often just swap big institutions for slightly smaller institutions.

So first there is a tactical challenge:

What is the best technical process for closing a hospital or a care facility?

50 years of deinstitutionalisation practice suggest that some of the most important factors include:

It is critical not to make the negative critique of the institution the only rationale for the change. Systems and people do not cope well with being told everything they are doing is wrong. This only encourages desperate defensive resistance. Deinstitutionalisation must be about hopeful transformation - people, families, neighbours and professionals all need a clear and secure framework for change around which they can build better solutions.

But more fundamental questions are not tactical - they are strategic:

What are the forces that are creating and recreating institutional patterns of power in our communities?

How can we help society to evolve so that we do not exclude, segregate or evict out fellow citizens?

It is only if we start to ask the right questions that we can start to uncover strategies for sustaining deeper deinstitutionalisation. If we do not start to ask the right questions then we are condemned to respond to problems with the same habits and solutions that have been defined by over 200 years of institutional thinking and practice.

To cover the right questions we must be prepared to look at the longer history of institutionalisation and the many wider forms it takes in the modern world. For instance, if we consider the intellectual social and economic forces that created institutionalisation in the nineteenth century (and earlier) there are some critical factors that made institutionalisation possible:

Today many of these forces are still very powerful.

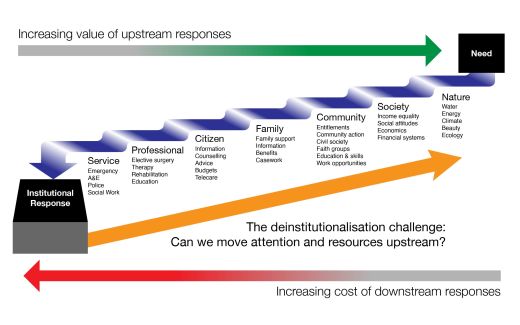

There is also a fourth factor, which is that the systems that we’ve created to respond to the ordinary problems people face still have a high degree of institutional gravity. We’ve built systems which pull resources and attention towards institutional solutions and which rarely manage to move their attention to the real causes of the initial problem. This downstream drift towards institutional control applies far beyond care services. In many areas we see resources committed to sub-optimal solutions, and there are no counter-balancing forces that encourage us to ask:

What can we do to prevent these problems in the first place?

The figure below comes from my report Heading Upstream, which describes one local government that is trying hard to make this shift towards helping communities, families and citizens have the resources and authority to solve problems in their own way. But even the best local government is still working in a society where larger social and environmental forces erode citizenship.

Figure 1. Heading Upstream

Citizen Network is a growing cooperative community of people and organisations committed to exploring the alternatives we need. We have active networks working on basic income, self-directed support, peer support, environmental action and neighbourhood democracy. We are seeking to wake up ourselves and the world around us, both to the harms caused by the institutional systems and the powers that create them, and also to the excitement and strength that comes from living a life of citizenship - connected, supported and supporting each other.

Now is a time for global thought and discussion on these ideas. The word deinstitutionalisation is perhaps not the most helpful - too technical and too negative. But perhaps people are ready to start talking about how we can create a world where everyone is welcome, everyone is seen as uniquely gifted, with something to share, and where everyone matters.

The publisher is the Centre for Welfare Reform. Beyond Deinstitutionalisation © Simon Duffy 2021. All Rights Reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

Deinstitutionalisation, Inclusion, intellectual disabilities, England, Article